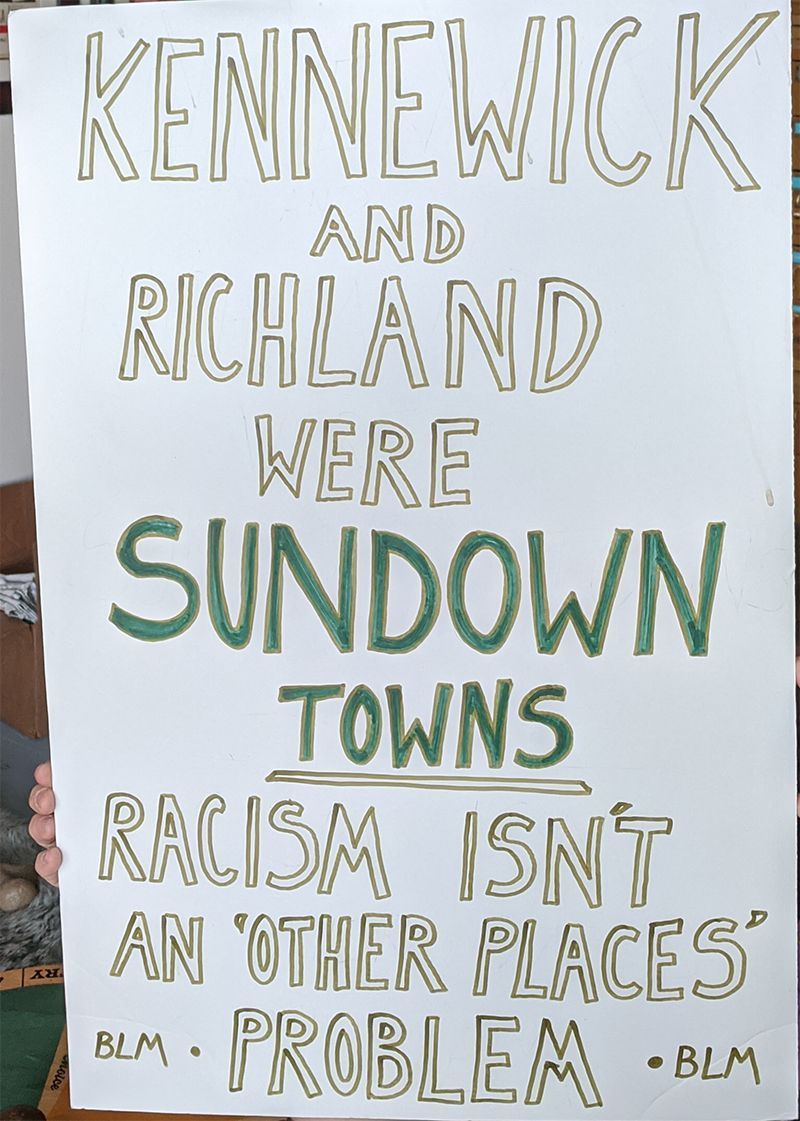

The other day I decided to walk down to the John Dam Plaza with my wife and a friend of ours to support the Black Lives Matter protest. I made a sign that said “Kennewick and Richland were Sundown Towns. Racism Isn’t an ‘Other Places’ Problem.”

In a world before I worked retail, I used to occasionally enjoy talking to people. But as an impolite person, I tend to steer clear of weather talk and go straight for the forbidden sins of conversation in race, religion, or politics. And a common thing one encounters when talking about issues of race with other white people, is a phrase like, “I’m so glad to live in Washington,” maybe expressing their hope and belief that racism is mostly restricted to the south or to Idaho. Or, on a different day, you might get someone saying, “It hasn’t been an issue since the 60’s” in an attempt to hand-wave systemic racism away, incorrectly assuming that racism magically ended on the very day when the “whites only” signs came down.

Either way, white people really don’t like talking about racism. They really don’t like to see it. Evidence of it, anyways.

The sign got a fair bit of questions and attention from people that afternoon who mostly wondered what it meant, and one older gentleman participating in the protest that assured me that Richland was never a Sundown town. Oh, local pride, you do show up in odd ways.

“Sundown town” is one of many terms used to denote a town who held racist policies after the Reconstruction, the period following the American Civil war in the late 1800s. These policies, both official and otherwise, restricted the demographics of a city, primarily the suburbs of the north and west.

You really don’t find sundown towns in the American south. They didn’t have to keep sneaky rules on their books to limit who could live where; they just burned a cross on your lawn or murdered you. Over 4,000 lynchings occurred between 1877 and 1950 in the American South.

Who needs cleverly racist HOA restrictions when you have murder and outright intimidation?

An executive order by President Roosevelt in 1941 prohibited discrimination for firms receiving federal money. So, as the Manhattan project came to life north of Richland (also displacing a number of Native Americans, but that’s a different story) in 1943, it was advised that 10 to 20 percent of the workforce at Hanford be comprised of African Americans to placate these new laws. The low end of this number was surpassed. Barely.

Dupont, the company in charge of hiring, restricted these already restricted positions to construction and cleaning positions which were part-time positions. African Americans had the option to live in segregated barracks on site of Hanford construction, where they could take place in largely segregated events, or they could live in Pasco, east of the train tracks. As housing in Richland was limited to full-time employees, and those positions were not available to Black or Latino people, options were limited to those two choices.

Settled by a largely southern population looking for good-paying jobs, those in charge of hiring at Hanford felt that their largely white workforce would not tolerate living in close proximity to Black people. Through selective hiring practices, they kept Black people out of Richland through much of the 40s.

Through many uphill battles waged by civil rights groups in Washington state such as the NAACP and National Urban League, as well as changes in contractors at the Hanford Project in 1947, seven black people resided in Richland by 1950.

Yes, seven.

Meanwhile, approximately 1,000 Black people lived in Pasco that same year.

The Atomic Energy Commission’s deputy manager at Hanford was quoted as saying “We have enough trouble here without having to cope with a Negro problem. We’ve got to think of our white majority, many of whom are southerners and would not stand for more Negroes here.”

And Kennewick in 1950? Zero Black people.

If you know an older Tri-Citian, you have likely heard of Kennewick’s past. That a sign hung over the green bridge between Kennewick and Pasco, letting local Black people know in no uncertain terms that they were not welcome in the city after dark. A Black Hanford worker was arrested and famously tied to a power pole at the edge of Kennewick for the Pasco police department to come collect.

Kennewick restrictions did not ease until 1968 with the passage of the Civil Rights Act, and oral histories exist of off-the-books restrictions existing well into the 1970s. My father worked as an engineer for Kennewick in the mid 1980s and recollects paper copies of maps still in occasional use where neighborhoods were labeled “WO” for “whites only,” and you’ll find many people with memories of the green bridge sign still living here today.

And Pasco* is not off the hook. It narrowly squeaks by a “sundown town” designation due to the technicality that its racist split happened within the same city limits. Details regarding the lived experience of the Pasco east/west division is well covered by the recent mini-documentary Pasco’s African American History.

The area east of the train tracks in Pasco (near what is now 4th Avenue) was where nearly all minorities were allowed to live. There was no running water or garbage service. The only way to walk into downtown Pasco was to navigate the unlit and treacherous Lewis Street underpass or to cross the train yard. Dupont provided one barracks in Pasco, but many were forced to live in makeshift housing as traditional housing was not available to them.

Law enforcement in Pasco created a new crime called “investigation” which had no specific infraction associated with it as a crime. Arrests for “investigation” were common in Pasco. The vast majority of restaurants, lunch counters, and even doctors’ offices were restrictive of Black customers, and west Pasco restricted loans to anyone of color trying to purchase property.

The foundation of the Tri-Cities was fraught with racial tension as areas fought to keep African Americans and other minorities out of their respective backyards through whatever means possible.

So you might say Richland was never a “sundown town,” and you’d be right that no sign with the n-word ever appeared on their bridge (quite possibly owing to the fact that no bridge existed at the time).

But despite the vivid image of bridge signs that stick in people’s heads as the hallmark of sundown towns, it wasn’t just that infamous sign that made Kennewick (AND Richland, AND West Pasco) a sundown town.

Through subtle and not-so-subtle racism alike, restrictions on loans, neighborhood covenants and cooperation between landlords, real estate agents, the police, and others, racism physically shaped the way the Tri-Cities was formed.

Seven in Richland. Zero in Kennewick. Nearly 1,000 in Pasco, 95% of those relegated to East Pasco. That wasn’t an accident.

Approximately 60 percent of wealth in this country is inherited, and much of middle class wealth is stored in the homes we live in. Homes east of 4th Street in Pasco can still be purchased for under $90,000 today. You cannot purchase empty lots in Kennewick or Richland for this amount and local fortunes have been made through selling small acreages, farms, and orchards as sub-developments in recent years.

By controlling where people lived in the Tri-Cities, those in power created a narrative about which areas were safe. Which neighborhoods were “good to raise a family in.” In turn, what schools and hospitals served you. How funds were distributed to you. And how police treated you.

I have lived here my whole life and have a lot of pride in the Tri-Cities. Our racist past is shameful, but it doesn’t have to be reflective of where we are now. People aren’t asking that you apologize for the sins of government contractors in the 1940s or Kennewick police in the 1950s and 1960s. Knowing our local history simply gives us more context for what people mean when they talk about systemic racism.

These racial divides weren’t all the result of official policy, and thus they never “officially” ended. In fact, these policies can still be seen today in the demographic splits between the three cities, and, more largely, in the economic split between whites and Black people in this country.

A 1948 study found that African Americans in Pasco listed a lack of municipal water supply and discrimination as their top two concerns. The top two concerns of whites in the area were crowded schools and the presence of Black people. The fact that we are able to forget this history is just another function of white supremacy.

Several folks defensive of Richland have come forward to proclaim that they had a Black neighbor in 1953 or that they remember a Black family living there in the late 40s. Going to Kennewick schools in the mid to late 80s, I can also remember that there was a Black student—just one.

That’s missing the point entirely. We are able to remember that one Black kid because of the town’s racist past.

There is no natural force that caused a 0/7/1,000 split in demographics in the 1950s and the dramatic difference we still see today.

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, as Carl Sagan would say. Knowing our history shouldn’t be something that elicits backlash.

You can’t solve problems if you can’t or won’t see them. Listen to Black people and People of Color when they tell you there is a problem in our community.

It’s up to us all to solve it.

For more reading and articles referenced in this piece:

- African American History at Hanford

- African Americans and the Manhattan Project

- Tri-City Herald

- Only Part of the Story Is Being Told About the Police Shooting in Pasco

- Loewen, James W. Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism. New York : Simon & Schuster, 2006.

- Robert Bauman, "Jim Crow in the Tri-Cities, 1943-1950," The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 96:3 (Summer 2005), pp. 124-131

- DiAngelo, Robin J. White Fragility: Why It's so Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. Boston: Beacon Press, 2018.

- Opportunity Atlas

- "The Tri-Cities is a sundown town"