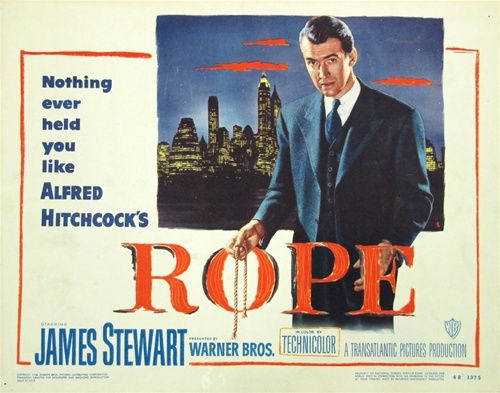

Start your autumn off right by wrapping your fingers around this one-take wonder from the Master of Suspense, available from Mid-Columbia Libraries

Alfred Hitchcock belongs to that league of directors who brought respectability and class to what many considered a lowbrow form of mass entertainment. Inexplicably, he pulled this off with a body of work that returns obsessively, time and again, to crime and madness — the basest corners of civilized man’s psyche. While many of his most deranged characters make attempts to rationalize their behavior (others can’t even see a reason for all the fuss), few can match Brandon, one of the two villains who also serve as the main characters in 1948s plainly-titled Rope. Moments after strangling an acquaintance from prep school, he assures his nervy accomplice, Phillip, that “murder can be art, too.” Not many filmmakers would have agreed more than the British man politely yet firmly gripping Rope’s reins.

Though he dealt in stories of wrongdoers, the world would not associate the name Hitchcock with straightforward gangster flicks or police dramas. The common thug fascinated him less than a breed of criminal that had wit, sophistication — someone who still managed to appreciate and attain inclusion into high society while suppressing antisocial tendencies. And maintaining one’s cool in the face of every setback, even ultimate defeat, appealed a great deal to this unruffled Brit whose facial expression and tone of voice (or lack of both) define droll. As the final moments of Rope close in on two-faced Brandon, he calmly undoes the necktie of his pressed blue suit and downs a highball. To the very end, style and comfort become his salvation and last weapon against mediocrity.

In perusing his own filmic arsenal, Hitchcock dispenses with the severe blades of the celluloid cutter as much as possible (a restraint he would gleefully toss aside with Psycho over a decade later). I counted less than ten edits over the entire 80-minute, told-in-real-time tale of Brandon and Phillip. Like an unseen ghost, the camera weaves back and forth across an apartment where the killers have invited their victim’s friends and parents, ignorant of the murder, to a dinner party of supreme perverseness. The graceful, hovering presence of the lens almost seems to mimic the effortless charm Brandon radiates as haughty host.

Yet, as the awkward cuts disrupt this dream of unbroken visual harmony, Phillip’s guilt-fueled verbal outbursts start to unravel his partner’s perfect plan. Innocuous faux pas like a guest mistaking another for the deceased loom as damning accusations to Phillip. Feebly, he bats away invisible attackers, unaware that an unseen camera eye remains his truest and harshest judge.

One of the most (literally) chest-clutching moments arrives after dinner. Up to this point in the film, Hitchcock has kept his camera on the move, serving viewers a variety of visual compositions. Now, almost in response to the partygoers having their appetites appeased, the camera takes a brief reprieve from the hubbub. Its gaze quietly rests on the hushed activity of a solitary character: Mrs. Wilson, the maid. On her, the lens stays rigidly focused for almost two endless minutes as she goes about clearing off a chest improvised as a dinner table — which contains the killers’ handiwork. Her silent commitment to the task at hand brings to mind another professional at work here; though the man keeps hidden from our eyes, Hitchcock’s skill shines onscreen.

As does his devilish sense of humor — films like Rope not only showcase his flair for injecting a bit of the macabre into the mundane (like a corpse inches away from an oblivious housekeeper), but panning for comedy in a subject as grisly, squeamish, and culturally verboten as killing. On a whim, Brandon gets the piquant notion to incorporate the dead man’s makeshift coffin as a centerpiece for his party. No doubt the sight of socialites clamoring for paté directly above a future feast for fish tickled the rotund Hitchcock. Who says death doesn’t deserve a lively makeover once in a while?

In the words of the director himself, “Drama is life with the dull bits cut out.” To him, boredom in his fans equates to a crime punishable by execution (at least to his career). Despite this fear, he bound himself to projects that pushed his ingenuity for keeping audiences entertained. The script to Rope derives from a British play set entirely in one locale. The challenge for Hitchcock, then, involved calling upon his powers in one medium (film) to do proper justice to a work created for another (theater). He succeeds in surpassing the limitations imposed by the mise-en-scène through restless and inventive cinematography.

The boxed-in staginess of this particular production can’t be rubbed out completely, however. The director agreeably acknowledges this in little touches like the large set of draped rear windows that, when opened at Rope’s start and closed near its end, remind one of the transition between acts. But it also signals the only destiny for two men drunk on delusions that they sit above a universe of morals: pull on the wrong rope, and it’s curtains.