When my mother came to America, she felt she had come to a place of immense opportunity for women.

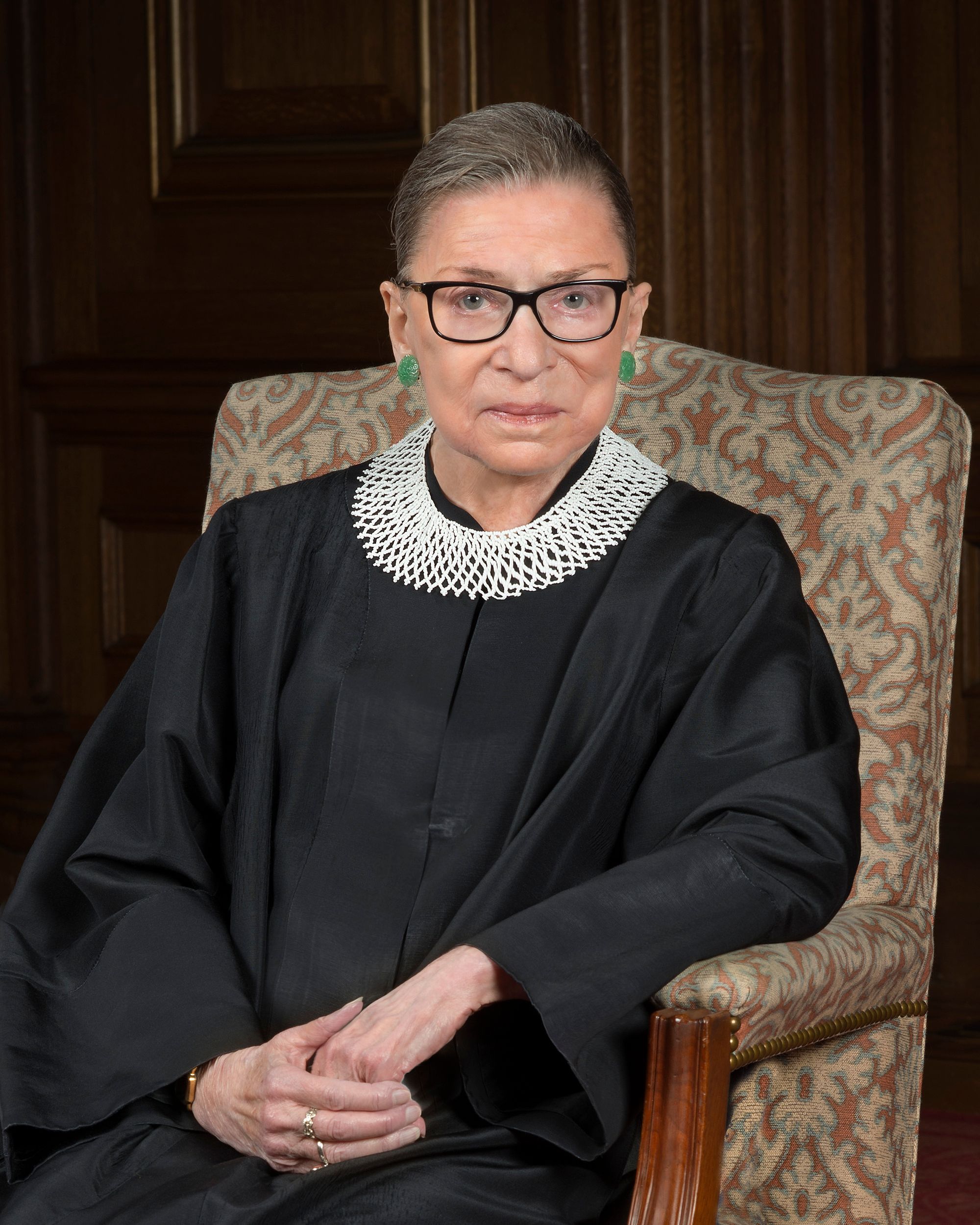

Her homeland, Turkey, has more ‘machismo’ than almost any other country. It is devoid of heroic women’s stories, lacks cultural icons like Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and still has no modern-day politicians as strong as Kamala Harris.

When my mother first touched ground in America in the 1970s, she may have been fearful had she known that one day she would have only granddaughters. She may have feared for their education, ambitions, or even lives under the outlook on lifestyle and healthcare for women at the time.

Thankfully, at the same time as my mother was unpacking into her first house in America, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was already almost a decade into her work with the ACLU bringing cases to the Supreme Court. The year my sister was born, Ruth Bader Ginsburg argued her last case in front of the Supreme Court to support a woman’s right to fulfill her civic duty as a member of a jury. By the time I was born, she was already a federal judge.

Appointed when I was only nine, I don’t remember a time in politics without her influence. Because I fear it will be a long time before we see someone like her on the Supreme Court again, I take her passing and replacement at this time as a huge threat to liberty as I know it now (and would want for my daughters in the future).

Some may imagine that my heaps of praise for RBG stems from having all daughters, which I do. But it goes beyond that. RBG and the equality champions like her were laying a foundation for my benefit — not just for my mother, sister, wife, and daughters. Gender equality serves people of every gender.

The key step forward in social progress is achieved not when the shackles of an unjust past are removed from the oppressed, but when the oppressor takes positive action to share equally in the future. Moving forward always requires eliminating backward thinking more than anything else.

Since 2020 is the year we stop accepting what we cannot change and start changing the things we cannot accept — how do we continue to change for the better?

The insight leading to this article is in observing the notorious RBG’s infamous phrase of “I dissent.” This is based on the real concept of a dissenting opinion in Supreme Court cases where the minority writes a conclusion in opposition to the majority with their narrative and reasons.

The phrase “I dissent” may not reach the heights of “we choose to go to the moon”; its impact in 2020 may be more on par with the phrase “yes we can” from 2008, with its opposite sentiment of resistance rather than enablement—a political slogan for this generation of progressive thinkers and doers.

Dissent, consent, and assent

The simplest way to slice it is that dissent indicates an actual net loss in the decision maker’s eyes. It must be a threat or drain to something.

In my opinion, the hard “yes” would be consent, where you are willing to actually contribute your willingness and resources to the outcome.

In the middle, in my mind, is assent; you are willing to be a bystander either way.

Understanding the difference between consent and assent is one of the most basic Human Rights in a trust relationship — romantic or otherwise — and acting “with the consent of the people” should be the goal of government rather than “the consent of lobbyists and the assent of a people embroiled in wedge issue arguments with their Facebook friends.”

Thus, if we had a nine-person board and each of them could vote dissent/consent/assent—rather than just vote yes or no—you could imagine various voting scenarios that better reflect a moral democracy:

- If you’re considering the issue of how to spend taxes, you might simply need a plurality of consents with a minority of dissents, indicating that a compromise makes some people unhappy, but overall democracy is still served when there is more agreement than disagreement.

- If you’re considering expanding liberty, you might act when there is “No dissent, plus at least one consent,” since more freedom for some is always good for democracy, as long as nobody is getting hurt along the way.

- If you’re considering curtailing liberty, you could require a majority to consent, because anything else would be a ‘democracy’ where mostly neutral people are lumped in with a vocal minority of politicians trying to taking rights away from the people.

What kind of improved decision-making might we see by giving people more than two options when voting?

How about instead of WHO we vote for, we considered changing HOW we vote?

The consent/assent/dissent concept above is a complex example of a simple idea: alternative voting. The core concept of alternative voting is increasing the resolution on how we count votes to vastly improve the accuracy of opinion across the population. There are many ways to do it, most thought through far more than my speculative nonfiction above.

Second only to human rights, alternative voting is my #1 political priority for America. We could reimagine the ‘pick one’ system we have right now—or as it’s become now: “pick one as an act of revenge from slights real or imagined by the other side.” We could have a “check all candidates your approve of”or “rank these candidates by their alignment to your values”process, and it would build moderation in the candidates in such a way that we would be automatically seeking compromise rather than conflict when filling out our ballots.

Changing HOW we vote could have a bigger impact than WHO we vote for — as a nation and beyond. Further, with gerrymandering, the politicians have been choosing who votes for them for generations. This would be a major step in taking our power back.

Alternative voting would enable more moderate candidates to win in primaries and even potentially shift or collapse the Republican/Democrat duopoly into a multi-party system. Why is that important?

To me, single-issue voting, identity politics, and factionalism has run amok in the system, while real progress on foundational issues like the exploding budget deficit, campaign finance for more fair elections, and bolstering human rights for the next generation has been pushed aside. Not to mention the inhumanity of politicians who actively muse about their careers when asked about a pandemic that’s killed over 209,000 Americans and caused the deaths of over a million humans on this planet (as of the writing of this article).

Only Americans think Pepsi versus Coke is a real choice between drinks. Only Americans think two parties is a real choice. Neither Republicans (1980s fascists) nor Democrats (1970s Republicans) truly align with my agenda, yet I don’t want to throw my vote away waiting for a unicorn when I feel the system is already failing me.

The current system is a side effect of drinking so much political sugar water for so long that we’ve developed type 2 diabetes and can only cover our $500 a month insulin bill with our credit cards. Alternative voting could be like exercise to manage the condition—difficult to make a habit at first, but far more likely to help than waiting for a game-changing one-time solution like a political artificial pancreas.

In any case, I believe alternative voting moves closer to representing the 328 million unique political opinions in the United States rather than bickering over the 538 votes in the electoral college’s red or blue states.

A complete description of the thesis of alternative voting and its success stories can be read about in the book The Politics Industry by Katherine Gehl and Michael Porter alongside other well-reasoned key ideas that would improve Democracy itself, like publicly funded elections.

I believe successfully moving toward a non-binary outlook on voting is my generation’s greatest potential political revolution. It would recognize that there are many paths toward a better tomorrow through a vigorous debate that recognizes constructive dissent rather than vitriol. It’s the kind of democracy Justice Ginsburg would have wanted for you and your family, and we could have it in America if we just came to together and voted for a better way to vote.

Erik Ralston is a son, brother, husband, father, Tri-Citizen, and American—not an AmeriCan’t. None of his affiliated professional or personal organizations approved or reviewed this article. https://medium.com/@ErikRalston