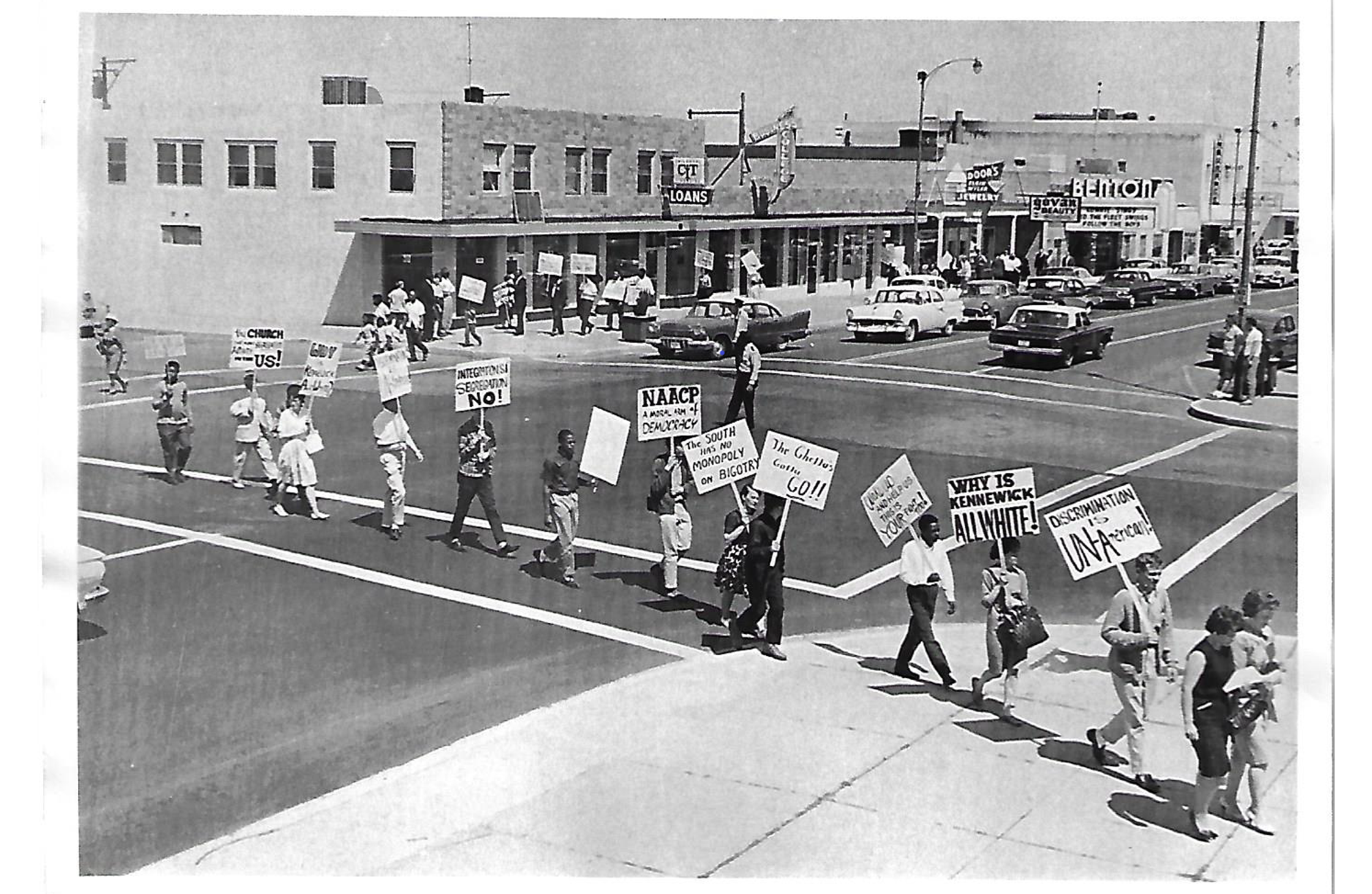

Civil rights protest in 1963 in Kennewick, Washington / Franklin County Historical Society Collection

The last decade has seen enormous upheaval within communities of Black people and other people of color across the United States, and the Tri-Cities has not escaped the sting of discrimination. Black people have fought for a place in South Central Washington for almost as long as Kennewick has existed.

In the beginning

Little is known about the people who came and went in those early days — trappers and traders, mostly. Some reports of Black travelers who may or may not have made it all the way. A man named York was recorded first, as a member of Lewis’ and Clark’s party. He was Clark’s servant, and descended from Africans. That is all we know.

Traveling through before 1836, John Hinds — a mountain man and trapper — spent time in the Pasco Basin on his way to the Waiilatpu Mission (Whitman Mission). Becoming the second recorded person of African American descent in the region. There may have been others, but their names or cultural backgrounds were not recorded. We can assume that some came with the Hudson Bay Company as people from many different lands did at that time.

Later, the pioneers and settlers came, including African Americans. They started townships such as Centralia and Bush Prairie, and then became railroad workers. Despite their clear belonging in and contribution to society, Black folk were unwelcome in the region. They were subjected to name calling, refused service, and feared for their safety if they went to the wrong places after dark.

In 1910, the census counted five Black residents in Benton County, all gone by 1940. From then until the 1960s, Kennewick did not have any permanent Black residents. In Franklin County (Pasco), the Black population almost doubled over the same period, from 16 to 29.

Sundown town

Local legend tells that sometime between the 1920s and 1950s, a sign went up on the Green Bridge (which was torn down in 1990) forbidding Black people from being in Kennewick after dark. Many older local residents have recalled its presence there.

Local DEI consultant Tanya Bowers published a letter to Tri-City Herald in September 2018 about the sign and its larger relevance:

This Pasco-Kennewick bridge bore a sign stating that Blacks had to be on the Pasco side by sunset. Kennewick was a sundown town, meaning that African Americans could not be within the city limits after dark. Pasco permitted Blacks to live on the east of the train tracks. Restrictive covenants and, after those were declared illegal, voluntary practices between real estate agents and homeowners prevented African Americans from buying or renting property outside of east Pasco.1

It’s during this time that Kennewick became a literal sundown town. But in practice, it had been one since the 1920s.2

We can pinpoint a date when the last known African American man can say they lived in Kennewick before it earned its nickname. On May 18, 1921, a Black farmer, Charles Cowen, was found by his farmhand shot in the heart. The kitchen window was open, and the kitchen table looked like it had been thrown about. However, since the front door was locked and Cowen’s keys were found in his pocket, police deemed his death a suicide. They claimed Cowen had climbed through his own kitchen window, went into his bedroom, and shot himself. Then they closed the case. Cowen was 38 and had lived in Kennewick for eleven years.3

Since Cowen’s death, only one Black person was confirmed living within what are now the boundaries of Kennewick for an extended period of time. Rumors suggest that Black folk were scared out of Kennewick even before the sign on the Green Bridge was put up.

In Franklin County, the picture was very different, with Black folk receiving greater inclusion within the Pasco community; and in 1924, Gladys Coleman became the first Black American to graduate from Pasco High School.

Separate but equal

Workers of all races flocked from the South to build Hanford, first during the Manhattan Project in 1942, and then a second wave during the Cold War and the building of McNary Dam in 1949. Southern workers brought Southern values, and racial segregation in housing was the norm — initially in barracks, and later in the creation of an entirely separate Black trailer camp at the construction site.

When on-site portable toilets were desegregated, white workers were so angered by the notion of sharing bathrooms with people who didn’t look like them that they placed ‘Whites Only’ signs up. On one occasion, in retaliation, some Black workers overturned one of the portable toilets while a white worker was inside. He sustained no physical injury — only perhaps one to his dignity.

Deciding where to house the rapidly expanding Black community was a challenge. Richland’s government housing excluded Black people — they argued it was for permanent workers and construction was ‘not a permanent job’.2 In Kennewick, in a 1950 report, the police chief is quoted as saying “If anybody in this town ever sells property to a [N-word], he’s liable to be run out of town.”4 At that time, Pasco was by far the most diverse of the three cities, and the only city to allow the Black community to be located within it.

Despite the relative diversity, the housing supplied to Black folk was often barely functional, located on the east side of the tracks. The city did not provide water or regular garbage service. In the beginning, there was one barrack and one bunkhouse for the entire population, forcing many into makeshift housing — trailers, tents, and chicken houses.5

In all, 15,000 Black workers arrived in the Tri-Cities between 1943 and 1945. The recruitment campaign was targeted at desperate Southern workers. Men and women poured in on the back of promises of high-paying jobs, and a chance to help in the war effort. In most cases, Black men were given construction work, or menial jobs, in segregated crews supervised by white men. Black women — educated and ready for clerical work — were employed only as maids, waitresses, and cooks.

The segregation continued through all walks of life: mess halls, social events, schools, parks. Not even in ‘progressive’ Pasco did people of all races mix.

Richland, unlike Kennewick, made some exceptions to their exclusion; and in 1947, Fred Claridy moved in.4 He worked first as a janitor at Hanford before becoming a metal operator, and married a woman named Elizabeth Walker, with whom he had a family. He bought two houses in Richland, living in one, and renting the other. He died in 1963.6

Claridy was an ordinary man, with an ordinary life — made exceptional only by its rarity.

Rampant racism

There’s no overstating the severity of the racism to which Black folk throughout the Tri-Cities were subjected. It was vicious, and far-reaching — practised by common folk and authority figures alike.

In one story, a Black man was arrested for riding in a car with two white men. Kennewick police, not wanting a Black person anywhere near their pristine jail cells, tied him to a power pole and called the Pasco police to pick him up. In another instance, a surveyor for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) noted that 80% (10 out of 12) eateries in Pasco refused service to Black people. A Pasco resident also said, in answer to his questions: “You couldn’t get a doctor to attend to a colored person in Pasco.”5

In the 1940s, the Pasco Police Department invented a new law. They called it ‘Investigation’, and it gave police carte blanche to arrest anyone without charging a specific crime. This new law made up one quarter of arrests within the Black community during the 1940s. Throughout the continuing boom into the 1940s, Black folk were arrested at a rate disproportionate to their representation in the population, including the majority of ‘Investigation’ arrests.5

Not even the church could escape it. In 1944, Black minister Reverend Samuel Coleman was asked by his white counterparts to build a church for Black people because they ‘no longer had enough room’ in their churches. In an epic display of petty revenge, Coleman agreed, but insisted on building his new church on the west side of town, smack bang in the middle of their white neighbourhoods. Despite threats, refusal of service, and several attempts at bribery, Coleman would not be persuaded to alter this plan, and was able to complete the church with the support of the NAACP and the National Urban League (NUL).7

One study after another

Dr. Warren G. Banner of the NUL was invited to the Tri-Cities in 1951 to conduct a study on Black integration in the region. He found it to be non-existent, and related his experience to his colleagues:

Racially discriminatory signs were common and unprotected. Negroes were routinely denied access to public accommodations and housing in the Tri-Cities. There being no good living accommodations opened to Dr. Banner himself, he was given board and room by Reverend and Mrs. Rudolph Anderson of the Pasco Methodist Church, who were members of the Committee.”8

In 1947, the Pasco Chamber of Commerce invited the Washington State College (WSC) to investigate racism in the area. The study found that the Black community was seen as an economic threat by some. That coupled with the racial prejudice of white immigrants from the South were the main issues in the racial divide.9

They found that Black communities lived mostly in trailers, without access to electricity or plumbing; only outhouses, and a few communal showers. They routinely received fewer services — the post office did not deliver mail east of the tracks, few hotels and boarding houses would accept Black residents, and only two out of 12 restaurants welcomed Black patrons. There were only two Black barber shops, and nothing for Black women. In movie theaters, Black people were restricted to the unfavorable seats. One woman complained about having to share the movie theater with Black people, saying to one of the WSC surveyors: “Sometimes when they turn the lights on, you find yourself sitting right in the middle of a bunch of [N-words]. You’re just scared to death!”

When white people were asked if they thought Black people should never live in the area, only 35% said “Yes”. Despite these findings, neither Kennewick nor Pasco acted to improve the lives of Black Americans living in the region.5

Another WSC survey in 1947 showed that many members of the Black community were proud of the work they did at Hanford, and believe that their presence has been an overall benefit to the area.

It gets better

With all racial divides, there are always white people who disagree with the status quo and want to join forces to change things. A branch of the NAACP was formed in the early days of Hanford, and included 180 Black and white members. They met with the Pasco mayor, and persuaded a few businesses to open their doors to Black people during their tenure. Unfortunately, lack of influence, support, and a regular meeting space — alongside fear of repercussions of stalling new memberships — caused the branch to close down only one year later.5

In 1946, a new company, General Electric Company, took over administration at the Hanford site and, together with the Washington State Board Against Discrimination, they reviewed past employment practices and determined they needed to change. Black people could now be hired as scientists and other white-collared jobs.

By the 1960s, the Black community in the Tri-Cities had started following the example of peaceful protestors in the South — marching for their rights, and building homes and communities within which they could thrive. In 1963, 80 people participated in a civil rights march in downtown Kennewick, protesting the curfew the city still had in effect at that time.8

Pasco schools also actively worked to end educational discrimination. They investigated the causes behind racial conflict in schools and took steps to hire minorities of all types, provide more multicultural educational opportunities, and provide more vocational education to give kids access to job opportunities. Investigators noted that Pasco schools had an excellent materials center for teachers, racially balanced classrooms, employed teacher-aids and bilingual teachers, established a remedial reading laboratory, and expanded the lunch program so no one was going hungry.8

In 1965, Richland allowed Black people to buy homes in the town boundaries, and C.J. Mitchell, his wife Bernice, and their six children became the first Black family to live there. Mitchell had worked on the Hanford site since 1947, and on huge construction projects, including McNary Dam and the Blue Bridge.10

An ordinary life, made exceptional by its rarity.

In the midst of all this progress, a Black family finally made it into Kennewick. A white teacher, angered by the city’s racial policies, agreed to rent the house to them in protest. John (an engineer with the Forest Service) and Mary Slaughter arrived in 1967 with their four children, and the family became the first Black Americans to live in Kennewick since 1930.11

The community’s hard work paid off in the 1970s. Young Black men were going to college and joining professional football teams — stars like Michael Jackson and Ron Howard, who played for teams all across the country. In 1976, Cynthia Moore was the first Black Miss Tri-Cities, and changed the perspective of beauty for a new generation. Other young Black folks were going to college and entering academia — Dallas Barnes became a member of the Washington State University faculty and helped struggling students succeed through tutoring and other programs at WSU.12

Working together

In January 1951, two white women, Florence Merrick and Lydia Pearce, started the Tri-City Committee of Human Relations and set off on a mission — to start a conversation between Black and white communities, and combat racism through friendly interactions. Over time, the greater goal became to improve living conditions for Black people.8

Another committee was founded in the early 1950s by John Savin, who said his biggest win (and one that endures to this day) was to secure a donation of land to build a park in East Pasco. After years of battling bureaucracy and going door-to-door for donations, the community pulled together to install a green outdoor space for Black Pasco residents to enjoy.8

Many other organizations worked together to improve lives in the East Pasco community — they paved streets, and installed water mains, sewers, and street lighting. A community-created youth center provided tutoring for students, and helped adults take night classes and earn their GEDs.

Political representation of the Black community also increased , thanks in part to the East Pasco Neighborhood Council formed in 1969. It became much more common for Black people to become members of city and school boards, or work within school districts.

When the idea of Columbia Basin College (CBC) was first proposed, many white people felt that it should be located in Kennewick (which was still a sundown town at that time). Obviously, doing this would harm the chances for any Black Tri-Cities resident to study past high school, as they would not be permitted to attend classes after dark, including the early evenings in the winter.

The NAACP and Committee of Human Relations worked together to protest the location, on the grounds that it was severely limiting to the Black population, and their efforts paid off. CBC was built in Pasco in 1955 and has served the community ever since.5

An ongoing battle

While we reflect on the lives that shape the Black community today, it’s important to remember we are still evolving. Having worked in a regional museum, bringing up the topic of race is still a very sore subject for the generations that lived during the period of the Hanford build-up. It is a topic surrounded in shame — a memory that not long ago, right here, Black people were treated as outsiders, unworthy of the basic dignity most white people took for granted.

It’s important that we own up to our mistakes, and talk about our history openly — not for the sake of shame, but to acknowledge everything that happened. We need to show younger generations that change is possible, and that changing for the better should be a source of pride, not of shame.

As we watch the world change before our eyes, and see that certain groups of people are being treated differently than others, we need to keep asking ourselves questions like: ‘If that was me, what would I think? What would I do? How would I feel?’ And we need to keep listening to people who have lived experiences to share. It only takes one person to start a movement that can make lives better for others in their wake.

Please help by donating to museums, universities, and archives that help give us a bigger picture of the experiences of minority (and minoritized) voices, so more articles like this one can be written in the future.

Ashleigh is a historian, folklorist, and cosplayer who loves living her best life.

References:

- Bowers, Tanya. Letter to the Editor, Tri-City Herald (September 2018)

- Ahmed, Afrose Fatima. “The Tri-Cities is a sundown town”: https://tumbleweird.org/the-tri-cities-is-a-sundown-town-again/

- Kennewick Courier-Reporter (May 19, 1921)

- Larrow, Charles P. “Memo on the Status of Negroes in the Hanford, Washington Area.” April 1949, box 6, Records of the Office of the Chairman, AEC (David Lilienthal, 1946-1950).

- Bauman, Robert. “Jim Crow in the Tri-Cities, 1943-1950.” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, vol. 96, no. 3, 2005, pp. 124–131. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40491852 (Abridged version on our website: https://tumbleweird.org/jim-crow-in-the-tri-cities/)

- Spokane Chronicle (October 26, 1963): https://www.newspapers.com/image/564586328/?article=6f99755c-f58f-4804-9439-78e4b6aca773

- Interview with Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Colman by Quintard Taylor (December 8, 1972, Pasco). Black Oral History Interviews, 1972-1974 (acc. 78-3), Washington State University Libraries, Pullman, Washington.

- Merrick, Florence. “A Condensed History of The Tri-City Committee on Human Relations” (Written on November 19, 1979 for the Franklin Historical Society)

- Wily, Jr, James T. “Race Conflict as Exemplified in a Washington Town.” M.A. thesis (Washington State University, 1949)

- Interview with C.J. Mitchell. Hanford History. (October 30, 2013). Hanford Oral History Project at Washington State University Tri-Cities: http://www.hanfordhistory.com/items/show/40

- Newman, Alexis. “John Slaughter (1933- )” (January 7, 2017): https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/slaughter-john-1933

- Interview with Dallas Barnes. Hanford History Project: http://hanfordhistory.com/items/show/2031

See also:

- Gilmour, Dori Luzzo. “How Jim Crow policies shaped the Tri-Cities”: https://www.nwpb.org/nw-news/2022-12-14/how-jim-crow-policies-shaped-the-tri-cities

- Oberst, Walter A. Railroads, Reclamation and the River: a History of Pasco. (January 1, 1978)

- Ahmed, Afrose Fatima. “The Tri-Cities is a sundown town”: https://tumbleweird.org/the-tri-cities-is-a-sundown-town-again

- Moonman, Logan. “Sundown towns? Yes, sweet dear Richland. And Pasco*, too.”: https://tumbleweird.org/sundown-towns-yes-dear-sweet-richland-and-pasco-too