“There is but one truly philosophical problem, and that is suicide.” So begins Albert Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus. Camus spends the next 150 pages breaking down the philosophical implications of, and the absurdist justifications against, suicide. Looking back to the foundations laid by the analytic greats like Kant and Nietzsche, Camus sets the stage for his embracing of the absurd to completely negate the act of suicide as ever justified, or more properly, a correct line of thinking.

A broad and wholly optimistic approach, as is absurdism in general, I believe that Camus espoused this generality because the act of integrating a pessimistic, if not wholly nihilistic, viewpoint and continuing living is counterintuitive at best and counterproductive at most and is therefore untenable. I intend to make the argument that not only is this not the case, but it is, in fact, one of the most enlightening of mindsets to adopt as praxis.

The why of it all

This coming March will mark the five-year anniversary of my most nearly successful attempt to destroy myself. It is not something I say with pride, nor do I share this with any sense of shame. I am sharing this because the years since have caused a need to objectively look at the causes leading to the event and the necessary changes that needed to take place to allow me to continue existing.

E.M. Cioran stated in All Gall is Divided: “Only optimists commit suicide, the optimists who can no longer be… optimists. The others, having no reason to live, why should they have any to die?” In my experience, both directly through action, and by proxy as a counselor, this rings true. The deepest depths of depression and emotional/physical pain rend from us our strongest attempts at optimism. The thought that no matter how bad things are or how bad they may get, that all will work out for the best; and when that doesn’t happen, the balance cannot be reconciled.

The act of optimism can be just as toxic as the most glaring negativity yet is felt as necessary to continue living a ‘life worth living’. This speaks to the way we as a culture view not only life for ourselves, but how we approach those who have attempted to end their life and remember those who have succeeded. The belief that ‘life will always get better’ or, in an even more shortsighted fashion, ‘by taking that step you remove the chance of it ever getting better’ is, by and large, the most selfish viewpoint that can be provided to those experiencing true existential crisis.

Just as the vast majority of self-identity and personal view of self exists on a spectrum, so too does the idea of leaving this existence. Valid are those who reach the proverbial end of their rope and seek help and successfully reenter the fold of the hustle and bustle of the everyday. Equally valid are those who see an end to the perpetual suffering and succeed in ending their suffering. The latter, however, are frowned upon and lamented against by the living. This is the case due to the living’s inability to see freedom from suffering as anything good due to its lasting effects felt only by the living.

I share both sides of this coin because I have been both the failed optimist and the Cioran subject with no categorical reason to live, and thus, no reason to die. I tried; it was a tiresome ordeal. This, however, is where the odd dichotomy lies, within me and within others. How can this be?

Bridging the gap

To have a firm or assumedly solid understanding of life in its totality, the good and the bad, the beautiful and the obscene, one must be open to both. The absurdity lies in the knowledge that while both exist simultaneously, to assume that one has any possibility of outweighing the other is fallacious and blinding. The darkness and pain exist, conjoined, with the loving and amazing. Problems arise when you attempt to lend too much credence to one side of the scale.

If we lose ourselves in the majesty of the blissful, we find ourselves blindsided by the inevitability of the darkness. Far too much weight given to the darkness will lead us into an anhedonic pit of unyielding despair. The darkness must coexist with light. My survival only amounted to invigorating my assurance of this. My feelings towards life and its existential woes remain unchanged. If anything, survival and beauty have reaffirmed my assurance that life is a farce through which we trudge.

Situational catalysts aside, the emotional and physical causes of my dalliance with death remain. So why then, one might ask, do I continue on? Looking back to Cioran, an all-around pessimistic figure who one may correctly assume rarely felt a moment of enjoyment in his life, we can be both. We can experience both the joys and sorrows of life without the need to lie to ourselves for comfort or an unfulfilled promise.

Into the great wide open

When expectations and judgements of what constitutes a fruitful and meaningful life are left by the wayside, a clearer picture of who we are and where we fit in the grandest of schemes becomes clearer. With this, we must also augment the ways in which we view those who seek an exit and those who succeed in finding it. There are few things more beautiful in this world than love. I can think of no better expression of love than the acceptance that those we love are no longer in pain, whatever form that may take.

Leaving behind the notion of true cessation of existential pain in the physical realm allows life to take on a more meaningful and immediate power. The feeling of a life wasted or opportunity squandered falls to the wayside when every moment takes on a power of its own. Assumptions of what life should be, not just for me, but for everyone else, are the building blocks of ruin. By not falling prey to the misguided notions and cultural misgivings of ‘the meaningful’, we open ourselves to the vastness of possibility and acceptance of the inevitability that awaits us all.

Let us love and learn and grow and die in peace. Let our lives be led the way we see fit. Let us leave our oft selfish and baseless judgements and assumptions by the wayside and allow ourselves the grace to find freedom from pain in whatever way we see fit. We are all in this together, whether we understand the reasoning or not.

If help is what you are searching for, there are many options out there. The National Suicide Prevention Hotline is a decent start and can be reached at 800-273-8255.

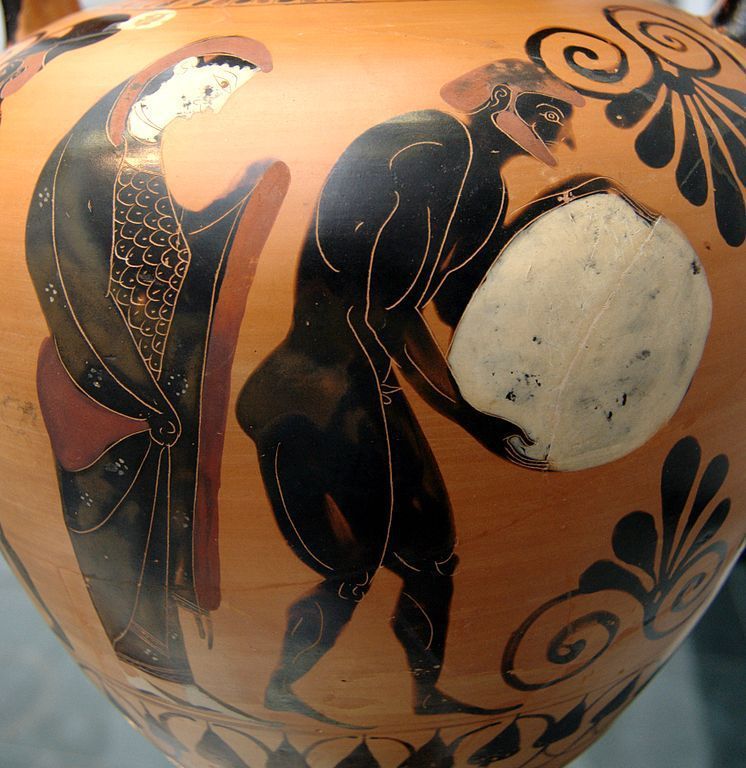

Main image: Nekyia: Persephone supervising Sisyphus pushing his rock in the Underworld. Side A of an Attic black-figure amphora, ca. 530 BC. From Vulci.

Marcel Ettesvold is a writer and thinker from the Tri-Cities. Absurdist Rambling blog: absurdistrambling.com