I find amazement in odd connections that seem to pop up over time — directly or indirectly — between notable lives or events with which I am already familiar. Details of a recent event, a chance twist in a conversation, or a startling fact stumbled onto in pursuit of other information often add more coincidences, ironies, and contradictions. So it is that the life of recently deceased high jumper Dick Fosbury provided a link between another Oregon sports legend, my former pastor, and a Richland sports star, in an incident that gained national attention 55 years ago, but now is buried under the dust of time.

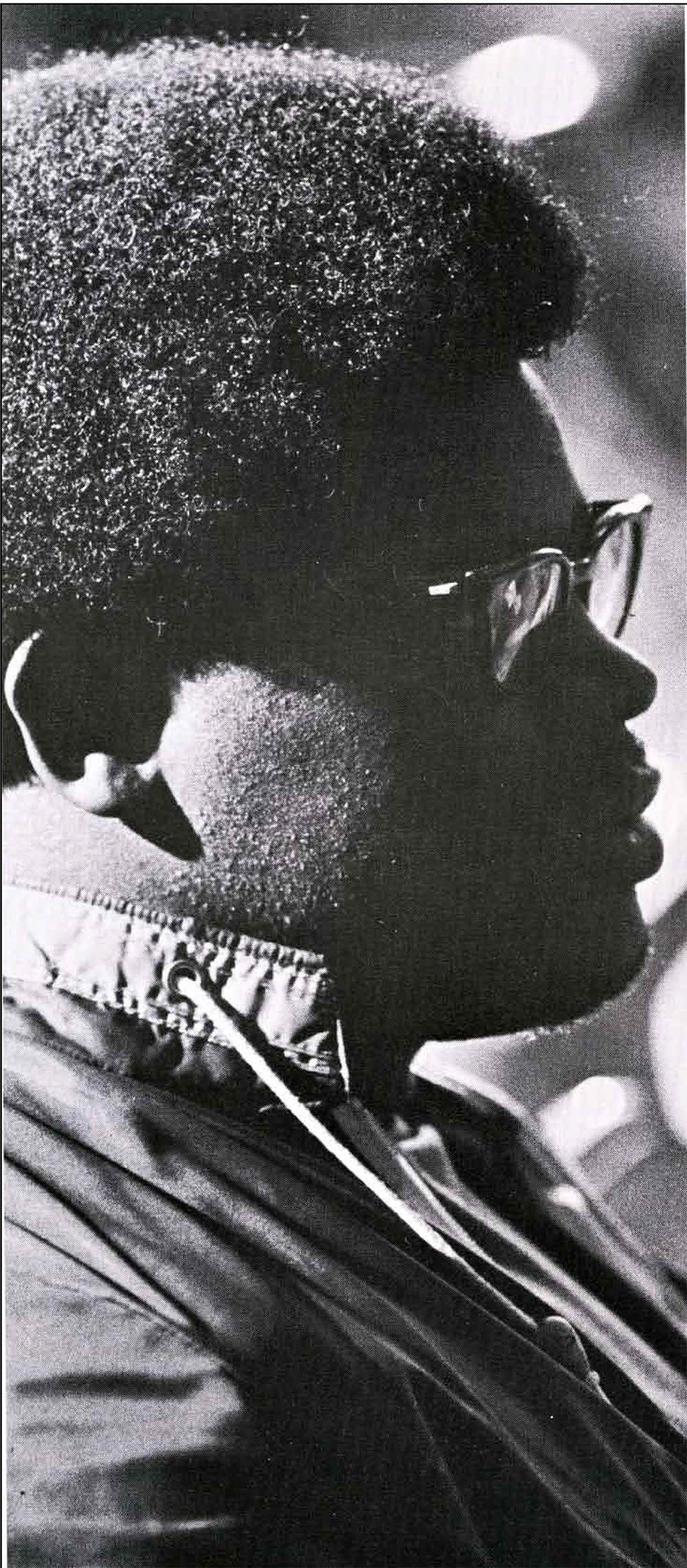

The pastor of my church in Silverton, Oregon, Father Durrant, sported a distinctive goatee and mustache. In the mid-1960s, he had served as the student Newman Center chaplain at Oregon State University. He grew the goatee and mustache, he said, in solidarity with a Black OSU football player who grew a goatee and mustache as part of the Black self-awareness and civil rights movement of the time. Though grown during the off-season, OSU Head Coach Dee Andros (a.k.a. “The Great Pumpkin” due to his girth and his OSU-orange windbreaker) demanded the player shave it off or be ousted from the team. The story made national headlines when neither the player nor Andros gave in. Father Durrant didn’t name the player, but I knew from coverage in the Tri-City Herald those many years ago that it was former Richland High School football star Fred Milton.

I also remembered Milton from a large plaque on the north wall of the Carmichael Junior High gym listing record athletic feats of past students. Milton had a phenomenal number of push-ups — an indicator of his impressive strength. Nearly 60 years later, Milton still holds the Richland High School shot put record.

Before moving to Richland in the early ‘60s, Milton’s family were sharecroppers in Arkansas. A school social life picture I stumbled across suggests he was a popular and amiable classmate. Though Milton was a bright spot on the mid-’60s high school football team, the team had the dismal results to which the town and school had grown accustomed. That may be why four-year schools showed little or no interest in him. Milton’s next stop was Wenatchee Valley College, which at that time was a junior college football power.

There, Milton caught the attention of Coach Andros. Later, as OSU middle linebacker, he became the defensive anchor of the legendary (at least in Oregon) ‘Giant Killers’ of 1967–68. The unheralded team went unbeaten against three top-two teams in four weeks (rankings changed week-to-week). Unfortunately, due to an injury — and later, the goatee and mustache he refused to shave off — that was Milton’s greatest season there. (He was later to finish out his football eligibility with Utah State U, a team as dismal as that of his high school years).

Despite Andros’ reaction to Milton’s facial hair, it’s difficult to determine how much of it was racially motivated as opposed to the more rigid, authoritarian nature of football coaches at that time. The ‘clean-cut’ appearance of players was requisite (in part, a response to the anti-authoritarian culture of the beatniks and hippies): short hair and no facial hair. But Andros’ intolerance would come back to haunt him and OSU. Numerous Black players resigned from the squad. For the next two decades, OSU football failed to attract Black players, either by its reputation or lack of effort, even while other major colleges were aggressively (and successfully) recruiting Black athletes. The caliber of OSU’s team plummeted. Still, Milton’s act of defiance contributed significantly to a growing awareness and sensitivity toward racial issues in Oregon.

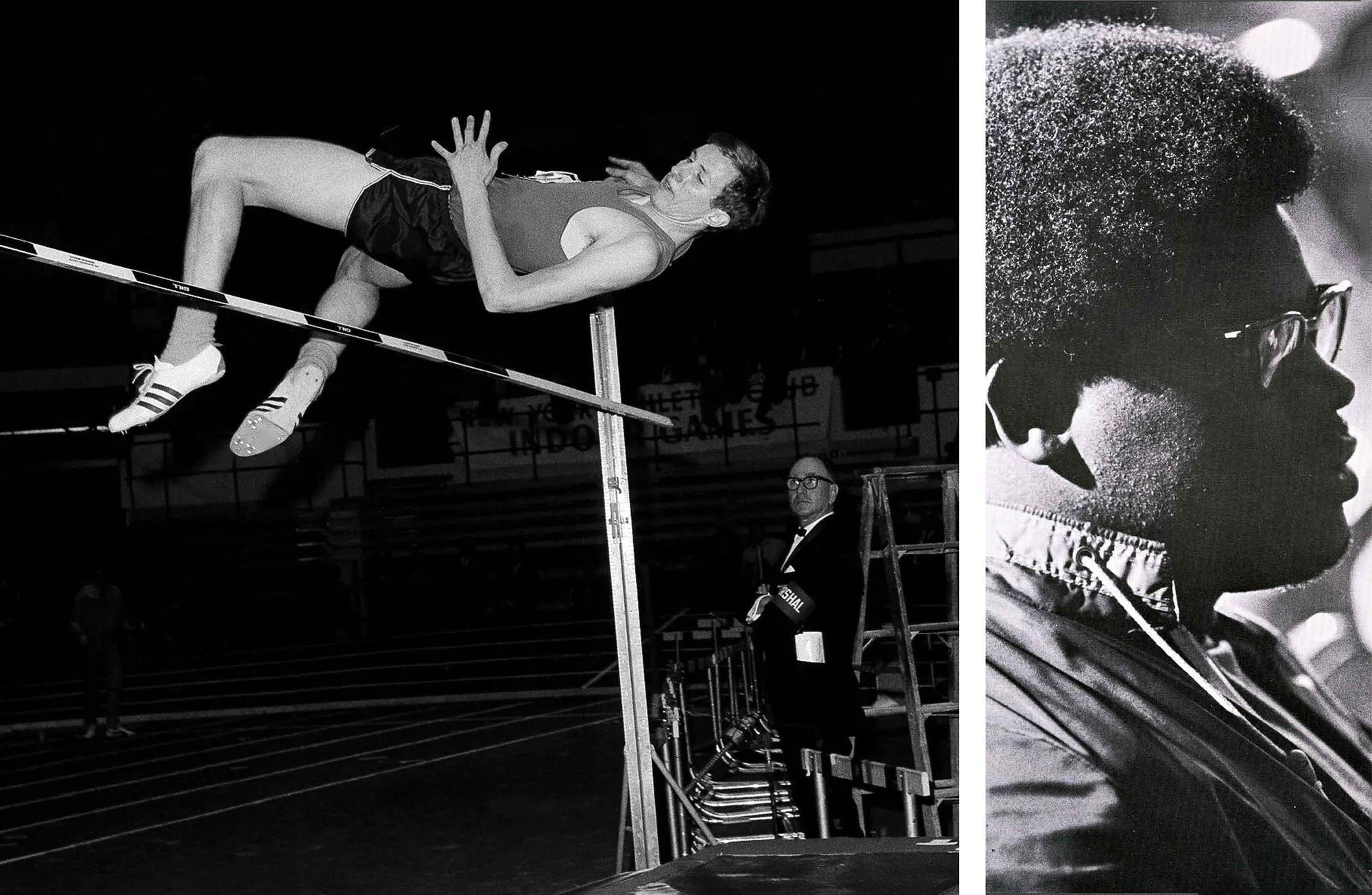

At the very time this incident was getting national attention, another situation at OSU also gained national attention: a high jumper from Medford had developed a new way of jumping that turned the traditional approach upside down. With his all-American-boy appeal, Dick Fosbury even demonstrated his back-down, belly-up jump over the bar (which had been deemed the ‘Fosbury Flop’) on The Tonight Show. It might seem odd that Fosbury would have enrolled at OSU rather than the track powerhouse University of Oregon, but his major was civil engineering, and OSU was the engineering school.

Fosbury’s new style at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City won him a gold medal — and set an Olympic record. Those Olympics were noted for other events, including American sprinters John Carlos and Tommy Smith raising black-gloved clenched fists from the medal stand in testimony to the struggle for civil rights. (Such things don’t always occur spontaneously; the silver medalist on the podium, Australian Peter Norman, gave full support beforehand and was ostracized by his country for years because of it. In 2006, Carlos and Smith were pallbearers at Norman’s funeral.)

After receiving his gold medal, when the national anthem ended, Fosbury raised a clenched fist in support of Carlos and Smith. But he did not receive the ugly wide-spread press those two did. When Fosbury returned to OSU in the notoriously prejudiced Southern Oregon, he used his prominence to stand up to faculty (and sadly, he had to stand up to some of his fellow students, as well).

Perhaps in coming to grips with not having lived up to the challenge of the times, a few years later, Andros reconnected with Milton, using his reputation and connections to help Milton play in the Canadian Football League. Milton and Andros became friends, and remained so until Andros passed in 2003. After all, they were co-giant killers.

Nagging injuries and Milton’s dissatisfaction with how players were being treated (maybe not surprisingly) ended his football career. Shortly after, he ended up in Portland, Fosbury’s birthplace, where he worked for a couple of prominent corporations, and later for the City of Portland and Multnomah County. In 1990, Milton ran for Multnomah County Commissioner and lost (in 2018 Fosbury ran for commissioner in Blaine County, Idaho, and won).

Milton died relatively early at 62 in 2011, attributable somewhat to his football injuries. Until the end, Milton continued to promote racial sensitivity in Oregon. During his time in Portland, he founded the Portland Inner-city Sports Club and supported African-American youths through special projects. Renowned for his service ethic and humility, Milton received a prestigious award from Nike for his volunteer work with youth sports.

If, despite push-up and shot put feats, Fred Milton has faded into obscurity at Richland High, he is enshrined in the Oregon Sports Hall of Fame as a ‘giant killer’. Arguably, it was a small and timely act of conviction off the field that left Milton’s biggest footprint on Oregon sports history.

Robert Sisk is a former Richlander and current social justice activist.