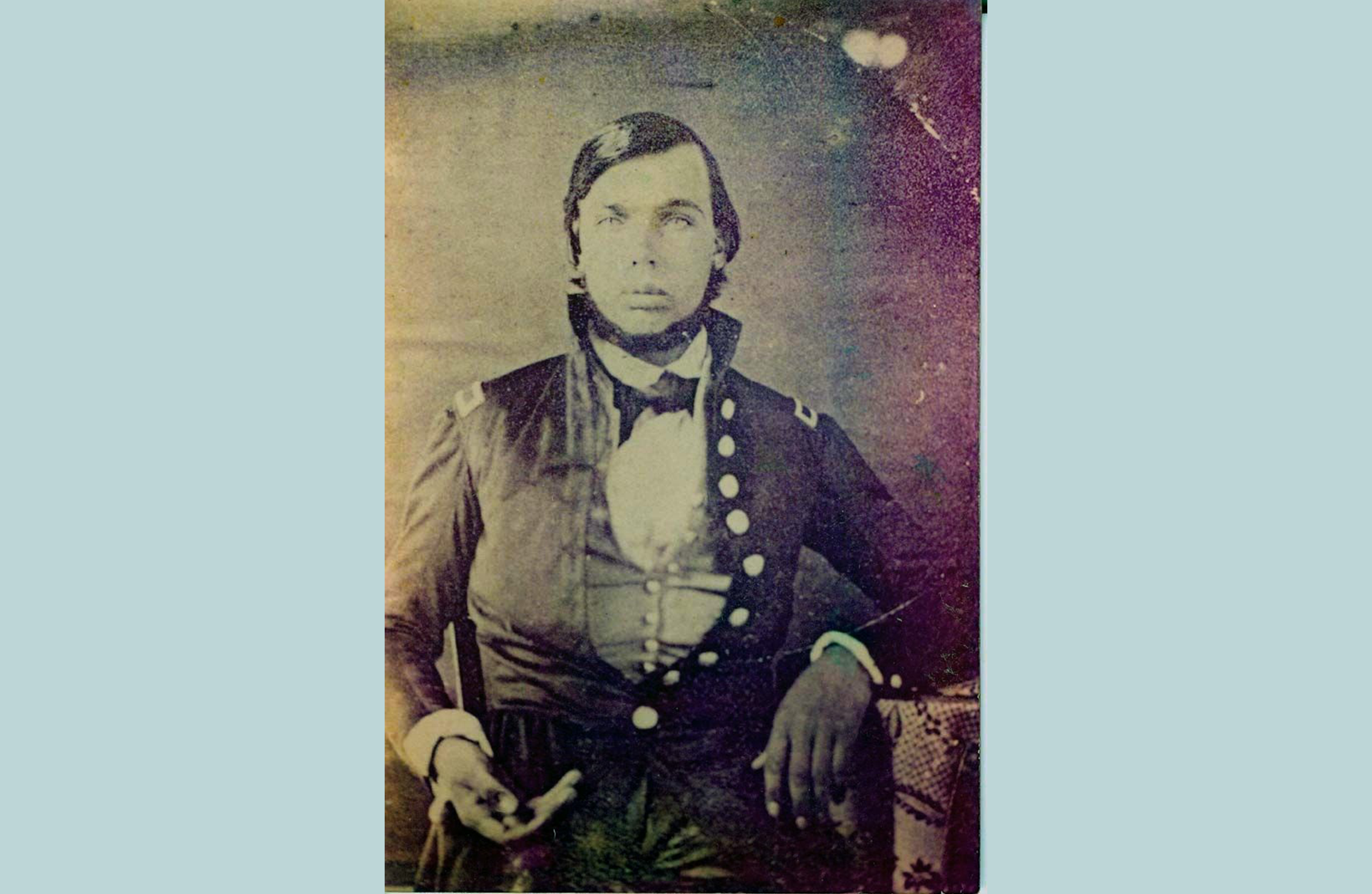

Lloyd Magruder, Jr.

During the mid-1800s, a man named Hill Beachy was a hotel proprietor in Lewiston, Idaho. He was well put together, which was unusual for the small town, known for being more Wild West than Madison Square Gardens. The people knew him for not only his somewhat snobbish behavior, but also his zero tolerance policy around slinging a gun in his establishment.

Everyone also knew about his friendship with Lloyd Magruder.

Magruder was a merchant, and on the morning of August 3, 1863, he and three trusted acquaintances left to find fortune in Virginia City, Montana. Magruder’s horse, Italy — named for the boot-shaped white patch on his rump — and one hundred mules accompanied them on the journey.

During his travels, Magruder sent frequent updates to Beachy. We know, for example, that a few days out from Lewiston, Magruder met with a scout of his acquaintance named Bill Page, along with three men he didn't know. Magruder hired them as muleskinners (people who drive mules).

We also know that it didn’t take long for Magruder to sell all his goods in Virginia City. In early October 1863, Magruder informed Beachy that he would be returning to Lewiston and that his trip had been profitable — $30,000 in gold dust and $20,000 in coins would accompany him on the road.

Beachy waited for his friend to arrive. He waited … and waited … and Beachy’s excitement shifted to worry. One winter storm had come through, but it had passed days before. Eventually, Beachy became convinced that his friend was not coming, for whatever reason; so he decided to go find Magruder himself, and bring him home if he could.

Beachy’s plan was simple: hit every stage stop from Lewiston to Virginia City, and talk to the operators. Surely a mule train of that size would not go unnoticed. To his surprise, Beachy couldn’t find anyone who had seen Magruder’s party until he arrived in the Bitterroot Mountains, 260 miles away. Eventually, he narrowed the search range to a specific area and time. He was able to perform a cursory search, but the snowfall was increasing, making it impossible to find much of a trail. So Beachy went back home to wait, and hope.

A break in the mystery happened a week after Beachy’s return. The hotel stable groom informed him that a horse had just come in, and it looked like Italy. When Beachy, incredulous, went to the stables to check, there was a horse with the right coloring and a large boot-shaped white patch on its rump. When called by name, the horse responded.

Shocked at this turn of events, Beachy immediately returned to the hotel to track down the horse’s rider. When he learned that the man was at dinner, he decided to take a peek into the visitor’s room. A quick search revealed that the man was a Methodist preacher from Boise, Idaho. Deciding there was little chance the man was involved with his friend’s disappearance, Boise being much further south than Magruder would have been traveling, Beachy went downstairs to interview him, and learned he had purchased Italy in Walla Walla, Washington, about three weeks before.

This was the lead Beachy needed. He bought Italy from the preacher and set off for Walla Walla the next day.

When he arrived at the place where Italy had been sold, the proprietor confirmed that the horse had been one of four, sold by four men claiming to have struck it rich in the mines. The men said they were heading back home, wherever that was — the proprietor did not know. The bill of sale listed their names: William Page (Magruder’s scout acquaintance), D.C. Lowry, David Howard, and James Romaine.

At the Walla Walla stage stop, Beachy inquired if the men had been through. They had, he learned, on October 14, and had headed to Portland, Oregon. Knowing he now had probable cause, Beachy wrote to the Sheriff of Lewiston, and to the governors of Oregon, Washington, and California, falsely identifying himself as a Sheriff in these latter three letters. His hope was that the men would be arrested if found.

The next morning, Beachy and Italy saddled up for their quest and headed to Portland.

When they arrived, it didn’t take long for Beachy to sniff out evidence of the men he was hunting. While William Page had mostly kept to himself, the other three men — Lowry, Howard, and Romaine — had been big spenders, which drew a lot of attention. All four men had left together on a steamer bound for San Francisco ten days before Beachy arrived.

The next steamer to San Francisco was in three weeks. Not wanting to wait that long, Beachy and Italy hit the road and traveled to the city on their own steam. While passing through Yreka, California, he learned that there was a telegraph link to the city. What a stroke of luck! Posing as a deputy sheriff, Beachy wired the San Francisco police with descriptions of the men, hoping that they would be arrested. However, when he arrived in San Francisco, the police had not taken any action. They (rightly) accused Beachy of impersonating a police officer, but — thankfully, due to another stroke of luck — did not bring charges against him for it.

Beachy stepped out into the streets of San Francisco, and realized the size of the task he had set himself. Even in the 1860s, San Francisco was not small. It was a hub for miners. Unlike in Portland, free-spending, loud-talking, hard-drinking miners would not stand out here; there were too many to count!

However, Beachy would not let that stop him. He set to work, starting with the finest hotel in the city. Right away, he got a lead. The four men had stayed at the hotel for about five days when they first arrived, but had since moved on. Beachy had a feeling they were still somewhere in the city, and after two more weeks of searching, he found William Page booked into a small hotel on lower California Street.

The encounter was not dramatic. When Beachy introduced himself to Page, the man was happy to meet him, and told his story without coaxing. Page had met the other men about two weeks before they had joined Magruder outside Lewiston. While traveling, they had watched Magruder sell his goods, and had seen how much money he was making. The men had made a plan to follow the merchant to Virginia City, and steal his fortune on the way. Then Page had overheard the other three talking about killing Magruder. He was caught listening and given an impossible choice: to join them or be killed. Page had chosen the former, to preserve his own life.

The men rejoined Magruder’s party as muleskinners, planning to kill him on the journey. They chose the night that Page was on guard duty to attack. Lowry killed Magruder with an axe-blow to the head, while Romaine and Howard killed the other drivers. They then selected one mule to carry the provisions, took enough horses to carry the men, and drove the rest of the animals off a cliff, tossing the bodies of the murdered men after them.

As far as the money went, Page claimed to have only received $5,000 in gold dust, and that $20,000 in gold coin had been buried at the bluff along the stagecoach route about a day outside of Walla Walla. Their reasoning was that if they claimed to be miners, it would be easy to explain the amount of gold dust, unlike the amount of gold coin.

Page was remorseful, and at Beachy’s urging, he told his story to the police. The police officers took the crime very seriously. They made quick work of locating Romaine, Lowry, and Howard, and by the end of the day, all three were in custody. The four men were returned to Lewiston on Christmas Eve, 1863 to stand trial.

In January 1864, Romaine, Lowry, and Howard were convicted and sentenced to be hanged. Page, in testifying for the prosecution, escaped the same fate. Their sentences were carried out on March 4, 1864. By May, the snow had melted enough for the bodies of their victims to be found. Whatever gold dust remained was given to Magruder’s widow.

Beachy, still trying to help however he could, enlisted Page in a mission to recover the gold coins from where they were buried, but he searched in vain. Page could not remember under which bluff the coins were located. He died the following August, having never been able to recover the gold. Presumably, the coins lie hidden to this day, somewhere along the old stage route, about a day’s horse ride from the 1863 city limits of Walla Walla.

Ashleigh Malin is a cosplayer, historian, and folklorist who loves living her best life.

References:

- Hamilton, Ladd. This Bloody Deed: The Magruder Incident. Washington State University Press, 2025.

- Liz. “The Bitter End of Lloyd Magruder.” Blogspot.Com, A ghrá, 27 Feb. 2016, eaghra.blogspot.com/2016/02/the-bitter-end-of-lloyd-magruder.html