Editor’s note:

This is an abridged version, that has been edited with updated language, of “Jim Crow in the Tri-Cities, 1943–1950” published by University of Washington in The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Summer, Vol. 96, No. 3 (Summer, 2005), pp. 124–131. Reprinted with permission from Dr. Bauman and PNQ.

Content advisory: Tumbleweird is honored to include this piece about the History of the Tri-Cities. Be advised that it includes vulgar and racist language.

On a warm summer night in 1950, a preacher and two parishioners drove across a green bridge spanning a majestic river to a nearby town. The sole purpose of their trip was to buy hot dogs for a church picnic to be held the next day. The men were accosted by local police, told they were not welcome, and ordered to leave town or face arrest. The individuals, who were Black, had little choice but to comply with the police officers' commands.1

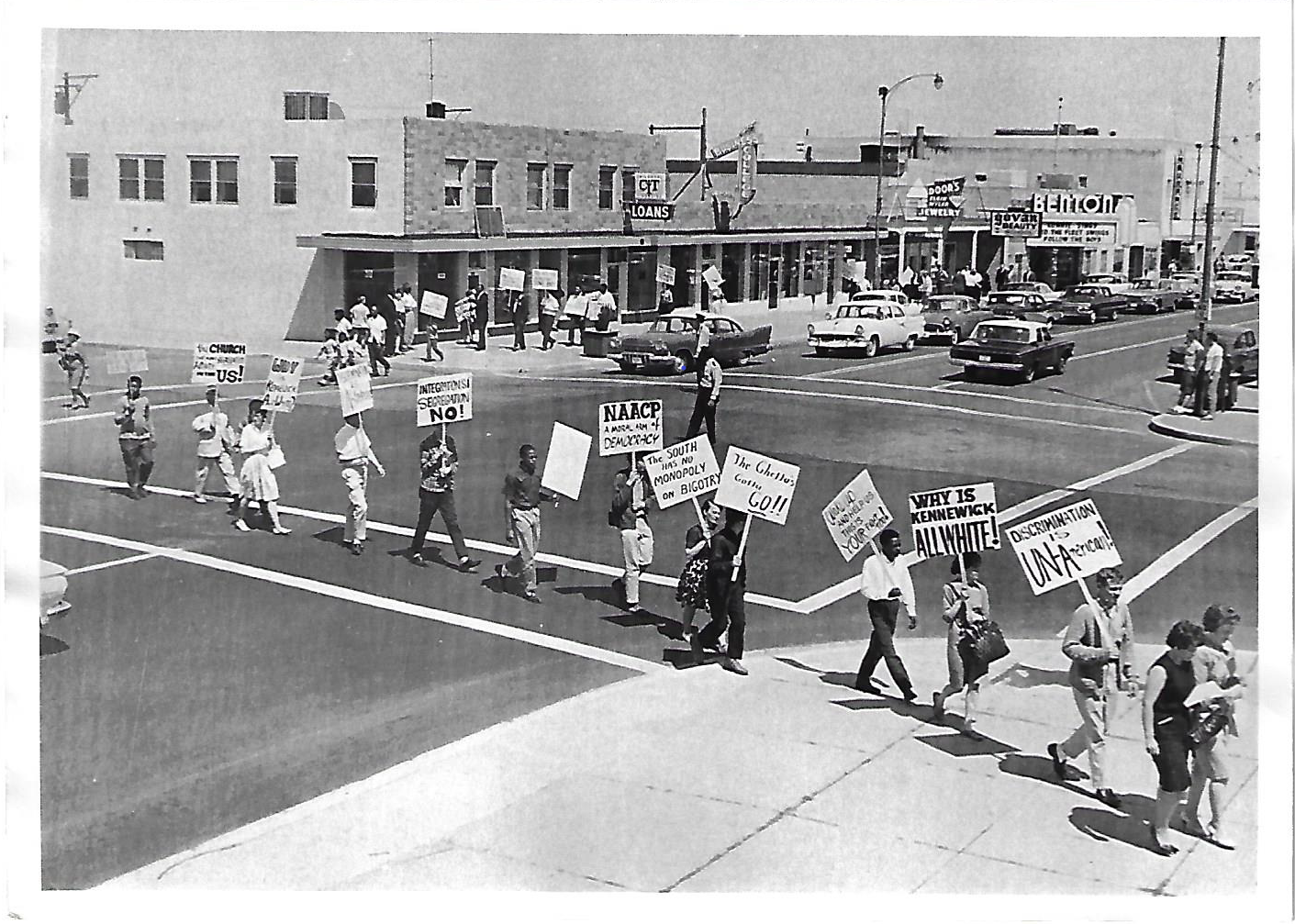

The river in this story is not the Mississippi, but the Columbia; the town is not in rural Alabama, but in rural Washington. This incident was one of several racial episodes that took place, not in the Jim Crow South, but in the Jim Crow Northwest — specifically, the town of Kennewick. Jack Tanner, a former president of the northwest branches of the NAACP, would later tag Kennewick "The Birmingham of Washington."2 How did Kennewick and its two neighbors, Pasco and Richland, come to have a Jim Crow system that many associate with the South?

In reality, segregation pervaded all regions of the United States to varying degrees. Rather than finding a haven in the Northwest, African Americans who migrated to the region during World War II faced a system of segregation not unlike that in some southern communities. In the Tri-Cities, Jim Crowism resulted from a combination of federal policy and the racism of white residents and recent white migrants to the area. African Americans in the Tri-Cities and state and national civil rights organizations regularly challenged that segregation and discrimination. Although they had only limited success, they paved the way for later civil rights activists, who would make great strides toward achieving racial equality in the area during the 1960s.

This story of segregation began when about 15,000 Black people arrived in the Tri-Cities in 1943–45 as the result of a recruiting drive by the DuPont Corporation, the primary contractor for Hanford in Richland.3 DuPont had been directed by the Manhattan Engineer District (MED) to construct the Hanford Engineer Works as quickly as possible. In order to do that, DuPont aggressively recruited white and Black laborers from the South. DuPont's managers believed that higher wage jobs at Hanford would appeal most to southern laborers. These laborers would build the facilities that produced the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan.

Kennewick, Pasco, and Richland were primarily farming communities at the time of the influx. Before the war, racial discrimination had not been particularly acute in the Tri-Cities, in part because the Black population was small and included only a few families.4 Their population rose from 27 in 1940 to just under 1,000 in 1950.

Unlike in major cities such as Seattle and Portland, few other racial minorities were present in the Tri-Cities when African Americans began arriving en masse. Approximately 150 Asian Americans lived in the area before the war, but many had been moved to internment camps by 1943–44. Mexican Americans did not begin arriving in the area in large numbers until the late 1950s.5 Because the Tri-Cities, unlike other areas of the American West, had a relatively small population of other minorities, Black people bore the brunt of white racism.

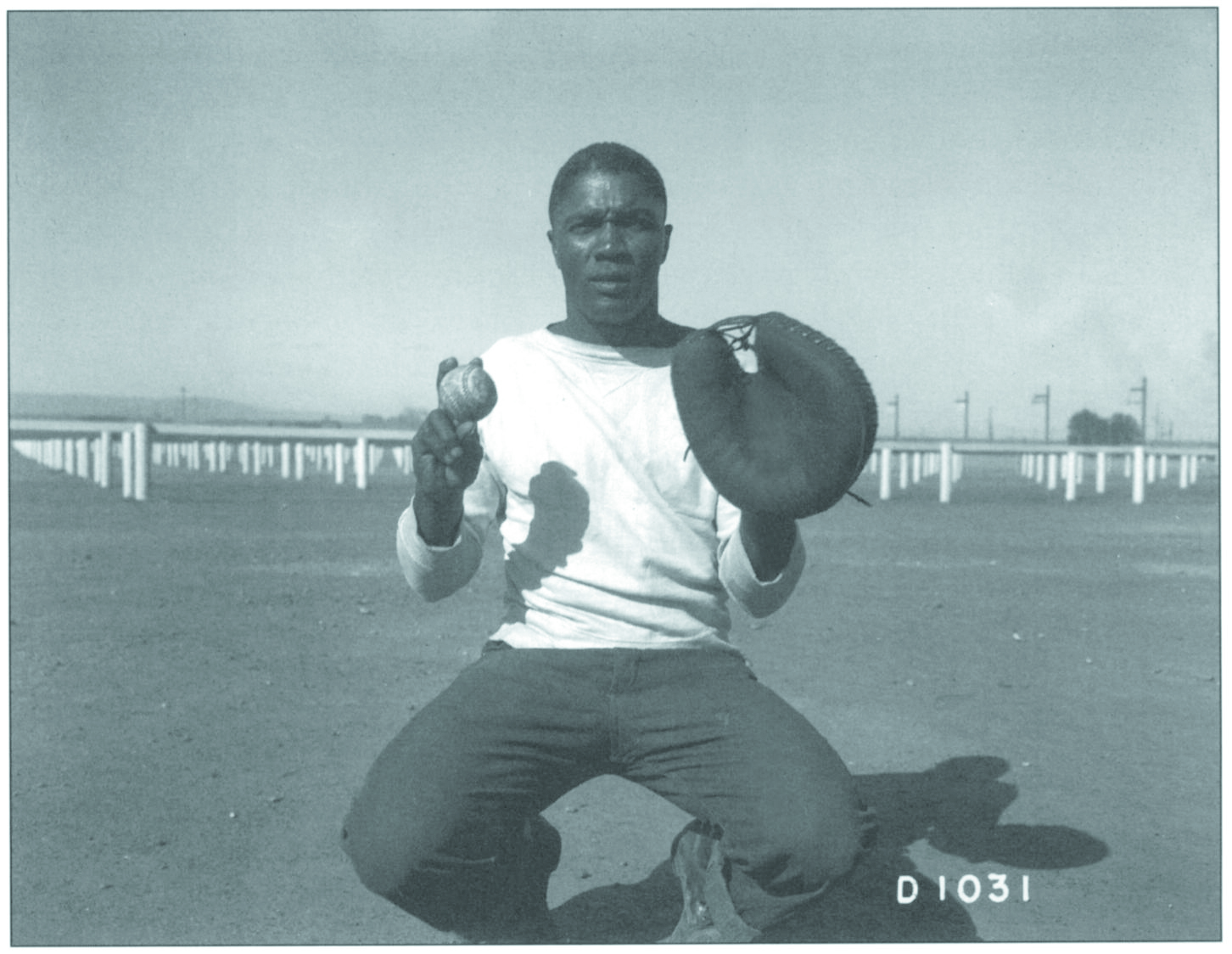

Black people and white people arrived in the Tri-Cities with differing expectations about race relations. Black people believed that moving north would improve their social status as well as their income. White people came north expecting that African Americans would be treated as they were in the South.6 The Manhattan Engineer District (MED) ensured that Black people never constituted more than 10–20% of the employees at Hanford. MED officials deemed that number enough to mollify the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) but not enough to scare away white southern laborers. Despite the need for workers, and the difficulty in finding them, the MED refused to hire more Black employees. Out of approximately 50,000 workers at Hanford in July 1944, just over 5,000 (4,100 men and 962 women), or roughly 10%, were African American.7

The MED, DuPont, and local government officials saw the hiring of Black laborers as a temporary expedient. Colonel Franklin T. Matthias, Hanford's commanding officer during the war, noted in his diary that the Washington governor Arthur B. Langlie, whose record on race was otherwise one of moderation, asked for his assurance that most construction workers would be returned whence they came after the war, "particularly the Negroes."8 In addition, the city of Pasco reached an agreement with DuPont officials that the company would pay to transport Black employees back to the South after their work was completed.9

Pasco officials also demanded that Black and white Hanford employees who lived in Pasco be transported to work on separate buses. African American workers fought back. In November 1943, they complained about the segregated busing to the Spokane branch of the NAACP. The branch president, the Reverend Emmett B. Reed, voiced his concern to state officials about what he described as "an attempt on the part of certain elements to impose upon our State . . . Jim Crowism." Thurgood Marshall, special counsel at NAACP headquarters in New York, recognizing the national implications of challenging the Jim Crowism of a federal defense contractor, wrote state and federal officials demanding an end to segregated buses. Four months later, DuPont stopped the practice.10

The NAACP’s pursuit of racial equality at Hanford did not end with the termination of segregated busing. At the end of May 1944, E.R. Dudley, NAACP assistant special counsel, arrived in Pasco from New York to investigate continued charges of racial discrimination at Hanford. Dudley noted that though the practice of segregated busing had been "cleaned up," there was still extensive discrimination at Hanford. For instance, he found that the overwhelming majority of Black employees at Hanford worked in construction or menial jobs. And though DuPont had recruited many Black women with promises of clerical jobs, it employed them almost exclusively as maids, servers, and cooks. Dudley challenged DuPont to explain why Black employees were always reclassified from one menial job to another but never promoted to white-collar jobs. Officials evaded his question.11

Labor was strictly segregated at Hanford, which is not surprising given the racial assumptions of white, working-class culture at the time. Most of the Black laborers at Hanford worked on all-Black crews with white foremen. Many of these white foremen had been transferred by DuPont from the South, and they brought their prejudices and Jim Crow ideas with them.12

Mexican Americans also experienced discrimination and segregation at Hanford. Colonel Matthias recorded in his diary that the use of Mexican American laborers would "require a third segregation of camp facilities, inasmuch as the Mexicans will not live with the Negroes and the Whites will not live with the Mexicans."13 DuPont provided segregated housing for those workers in Pasco.

Many of the Jim Crow codes that governed society in the South were also in place at Hanford. Black employees were strictly forbidden from eating with white ones. Of Hanford's nine mess halls, eight were for white employees only. One of the Black barracks had a pool parlor and soda fountain so that Black workers could relax and socialize away from whites. Most social activities at Hanford were segregated. For instance, Hanford officials planned separate Christmas events in 1944 for Black and white employees.15

During his investigation, the NAACP's E.R. Dudley found housing at Hanford strictly segregated by gender and race. In 1943, Hanford had 110 barracks for white men, 21 for Black men, 57 for white women, and 7 for Black women. Later in the war, Hanford created a separate Black trailer camp on-site. Interestingly, the toilets at the site were not segregated. This angered some white workers, who occasionally placed ‘Whites Only’ signs on them. On at least one occasion, some Black workers "overturned one of these buildings, along with its white occupant, who was not physically injured but was, of course, morally disorganized." The battle over toilets at Hanford reflected the larger conflict over racial segregation in the workplace.16

Those African Americans who sought housing off-site also faced a segregated and, at times, hostile environment. Housing in the government town of Richland was for permanent workers, such as those employed in production. Because Black people were hired only as construction workers, which were temporary positions, they were excluded from housing in the town. Housing in Kennewick was off-limits to Black people because of racially restrictive covenants. In fact, the city was hostile to the mere presence of African Americans. Kennewick police arrested one Black Hanford worker for riding in a car with two white men. They then tied him to a power pole until police from Pasco, where the man lived, came for him. Apparently, Kennewick officials did not want Black people in their jail, either.17

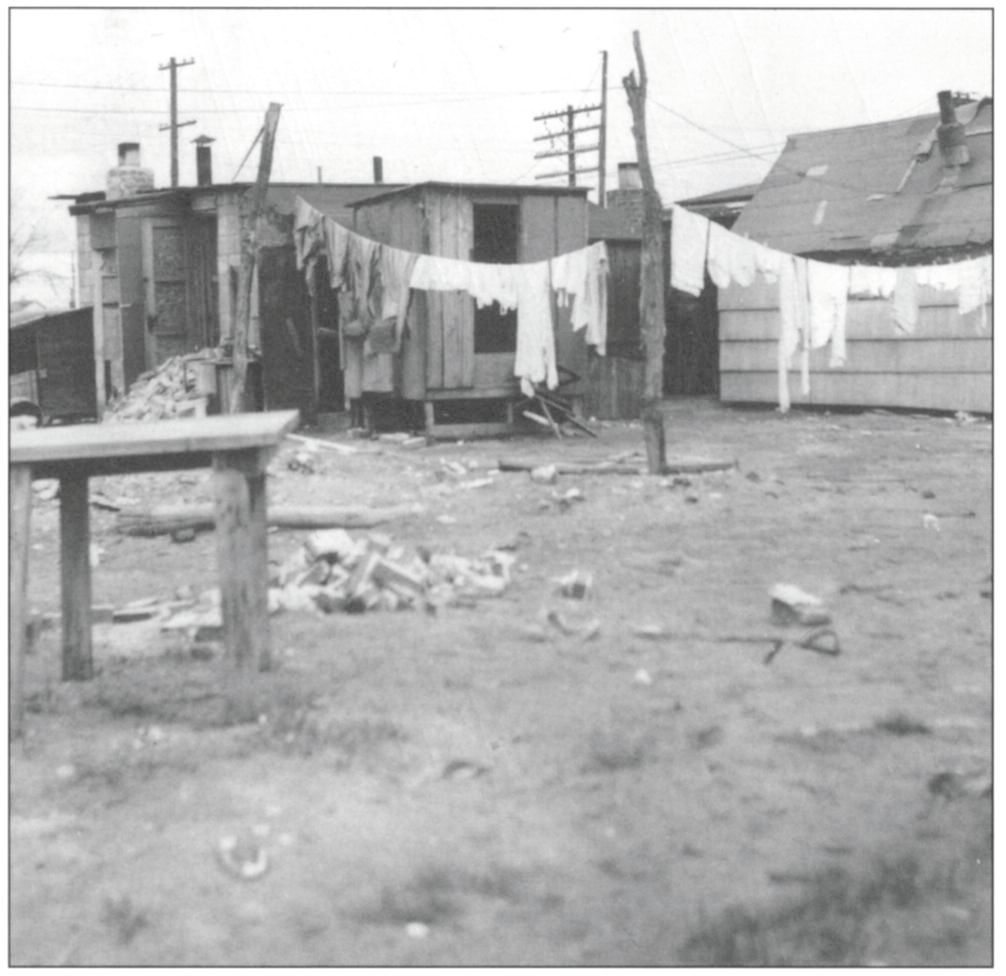

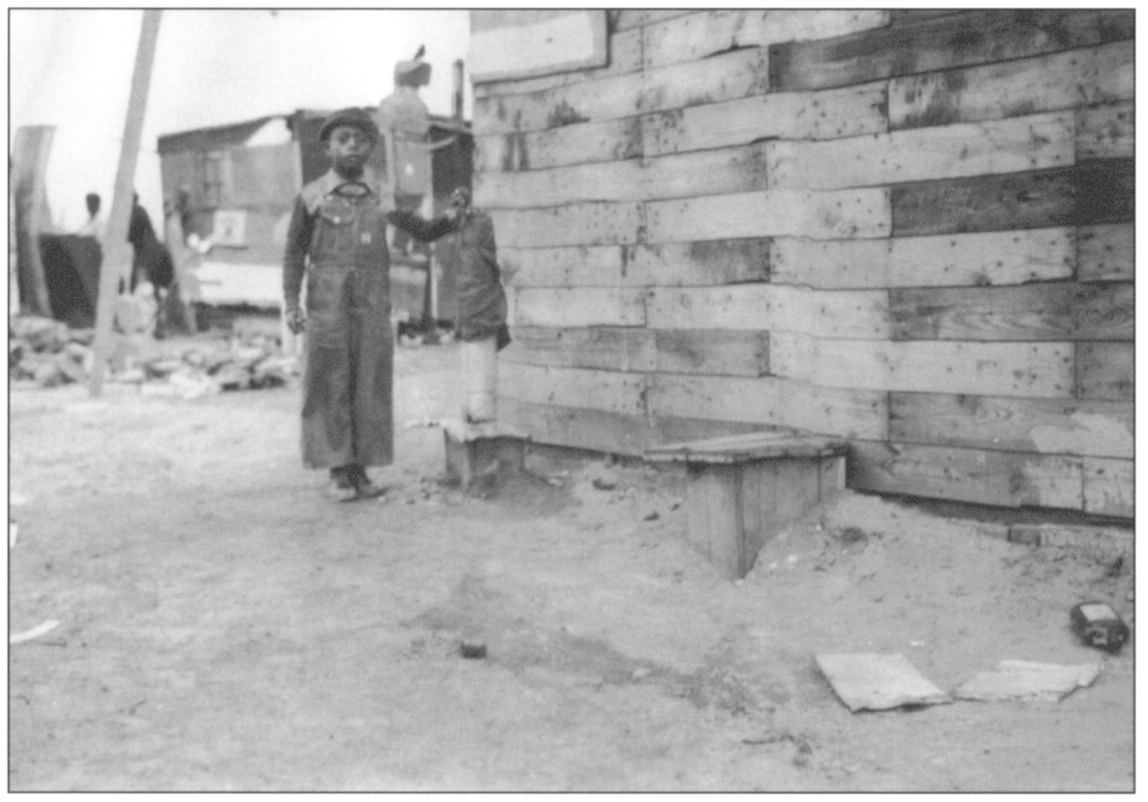

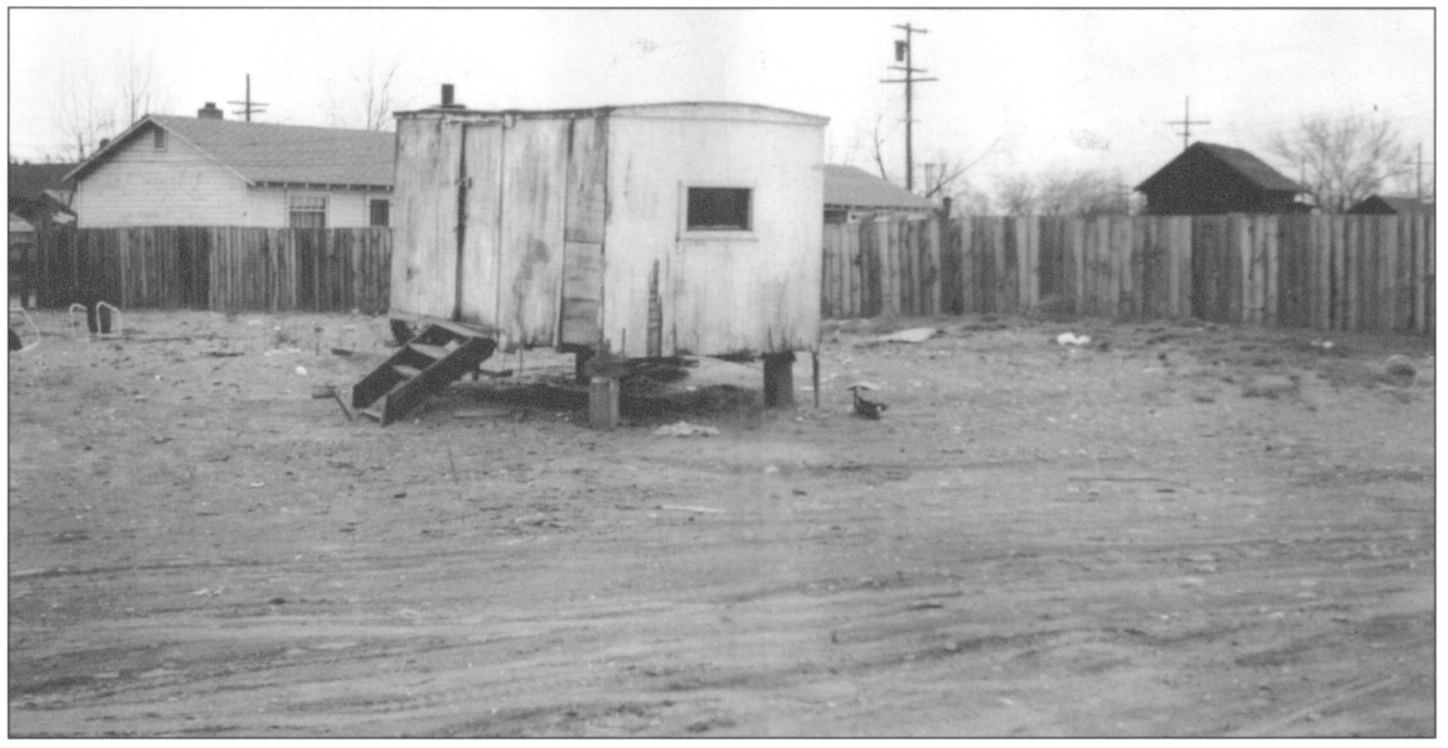

Pasco was the only one of the three cities that allowed Black residents. However, they could only reside east of the railroad tracks. In the words of one longtime African American resident of Pasco, "They didn't want no colored on the west side of the railroad track in 1944."18 The city did not provide water or regular garbage service to the east side. DuPont arranged for one barrack and one bunkhouse for "colored personnel" in Pasco, but many African Americans were forced into makeshift residences, including trailers, shacks, tents, and chicken houses.19

Dudley also found that Pasco businesses discriminated against Black residents, reporting that there seemed "to have been concerted action on the part of all business to deprive the Negroes of café service, bar and grill service, and most stores refused them the privilege of trying on" clothes while shopping. Dudley estimated that 80% of restaurants, soda fountains, and lunch counters in Pasco refused to serve Black people. He experienced this discrimination firsthand when the owner of Austin's Grill in Pasco told him that his restaurant "did not serve colored people."20 Black people also had difficulty obtaining medical services in Pasco. One African American resident complained, "You couldn't get a doctor to attend to a colored person in Pasco."21

Black residents in Pasco faced discrimination from law enforcement, as well. The Pasco Police Department invented a new crime called ‘investigation,’ which allowed police to arrest Black people without charging them with a more specific infraction. Roughly 25% of all arrests of Black people in the 1940s in Pasco were for investigation.22 Clearly, the Pasco Police Department, like many others across the country, targeted African Americans. What makes Pasco's policy unusual was how quickly it was constructed in a community that had virtually no pre-World War II Black population.

The NAACP decided to launch another fight at Hanford and to tackle Jim Crowism in Pasco, as well. They saw segregation at the federal government-controlled Hanford Site and the surrounding federally dependent Tri-Cities communities as nationally significant. Dudley — along with the Reverend Emmett B. Reed of the NAACP's Spokane branch and J.M. Hines and C.B. Smith, members of the newly formed NAACP Hanford branch — met with Pasco city officials to demand the end of segregation in the city. When the Pasco mayor offered a ‘compromise’ — persuading a few businesses to desegregate — Dudley informed him that the only compromise acceptable to Black residents "would be one where all Jim Crow signs were removed and Negroes permitted fully and without segregation or discrimination to participate in all public facilities and accommodations."23

Dudley and his colleagues next held a mass meeting at Hanford, where the corps officially informed him that they could do nothing about segregation because it was the corps' official policy, but that they would try to address some of the other forms of discrimination, such as hiring practices; however, no changes were made in that area, either.24

The Jim Crow system in Pasco did not prevent its African American residents from establishing the foundations of community life; indeed, it was the impetus behind the creation of the first Black church in Pasco. Seven white ministers and one leading white female resident asked the Reverend Samuel Coleman, one of a handful of Black residents in Pasco before the war, to build a church because, they argued, there was not enough room in their churches for Black congregants. The numbers of white migrants who had moved to Pasco to work on the Hanford project probably had, in fact, overwhelmed the local churches. But given the prevailing racial ideology of the time, these church leaders more likely approached Coleman because white residents were unhappy about attending church with Black people.25

When Coleman began constructing the new church on the west side of town, he faced determined opposition from civic leaders. Pasco's mayor, E.S. Johnston, told Coleman that if he built his church on the east side of town, the city would provide the water and electricity at no cost. In addition, local real-estate agents offered Coleman lots on the east side of town for five dollars each. After Coleman refused to construct the church on the east side of town, the Pasco City Council, in an effort to make the costs for the church prohibitive, changed the city code to require one toilet for every 15 people in a building, instead of one toilet for every 60 people, the previous requirement. No plumber in town would install the church's toilets, so Coleman had to hire someone through the National Urban League (NUL) office in Portland.26

Eventually, Coleman's persistence, along with threats of legal action by Seattle's NAACP office and Portland's Urban League office, resulted in the completion of the church on the west side of Pasco.27 By defying city leaders and building a church for a Black congregation on the all-white west side of Pasco, Coleman had created a small fissure in the foundation of segregation. His action, along with the desegregation of Hanford buses, was one of the few sustained challenges against Jim Crow in Pasco during the war years.

After the war, the number of construction jobs at Hanford declined, and many Black people left for larger cities, such as Portland and Seattle. However, a second, smaller wave of immigration occurred when the Hanford Site experienced another construction boom during the Cold War. Thousands of workers were once again needed for the expansion at Hanford, the building of the nearby McNary Dam, and a new pumping plant for the Columbia Basin irrigation project. Several thousand African Americans migrated to the Tri-Cities at this time.28

For African Americans, the Cold War was a period of decidedly mixed signals from the federal government. The State Department argued that segregation and racial discrimination at home injured American credibility abroad and made American democracy vulnerable to Soviet criticism. At the same time, the anticommunist hysteria of the Cold War severely impaired civil rights organizations and restricted ideology and political activism. Any individuals or organizations that pointed out American democracy's flaws, such as racism and segregation, were branded as communist and risked attracting the attention of the FBI.

For Black workers at one of the nation's key defense sites, the early Cold War years were a time of both opportunity and frustration. On the one hand, Hanford was an excellent place to work because of the numerous jobs open to Black people; on the other hand, those jobs were usually menial. But in the era of the Great Fear, most people were unwilling to complain about such discrimination.29

Virtually all African Americans at Hanford were employed as temporary construction workers, as they had been during the war. Realizing that their employment opportunities were limited, some braved possible recriminations and notified the newly formed Washington State Board Against Discrimination (WSBAD) about the situation at Hanford. Members of the WSBAD met with the complainants as well as with representatives of the Atomic Energy Commission, which had replaced the MED as the federal agency overseeing America's atomic arsenal, and the General Electric Company, the new primary contractor for the site. The WSBAD determined that "employment practices in the past may not have been exercised on a basis of equal opportunity for all." Persuaded by the board to improve minority employment practices, General Electric soon began to hire Black employees as scientists and other white-collar positions. Employment discrimination at Hanford, though, remained a problem for years.30

The end of World War II had not changed housing practices in the Tri-Cities, and most African American Hanford employees were again forced to live in Pasco. Though segregated barracks and trailers were still available on the Hanford Site for all workers, permanent housing in the government town of Richland remained available only to permanent workers, and not available to most Black employees (who were considered temporary employees). In 1950, only seven African Americans resided in the city of Richland because they held white-collar positions at Hanford. In addition, the city of Kennewick remained off-limits to Black residents because of racially restrictive covenants and local real-estate practices.31

Ray Henry, an African American Hanford worker who had arrived in the Tri-Cities in 1943, noticed increased tensions during the late 1940s. According to Henry, "The white people that were here just weren't as acquainted with Blacks . . . and many whites who came here for work were from the South."32 The significant population expansion and the resulting racial tensions led the secretary of the Pasco Chamber of Commerce to contact the Washington State College (WSC) field office in Pasco in the fall of 1947. On behalf of the Pasco and Kennewick chambers of commerce, city councils, and Kiwanis clubs, he asked that the college investigate and evaluate the problems caused by the area's population growth and demographic changes, to which the college agreed. In January 1948, Dr. Wilson Compton, the president of WSC, put Dr. T.H. Kennedy, chair of the college's Social Sciences Division, in charge of the study. They began to conduct surveys of local residents. One of the primary topics of study was race relations.33

The WSC study found that the reasons for increased racial tensions in the Tri-Cities included Black migration; latent prejudice in established white residents; the perception of Black people as an economic threat by some whites; and the racial prejudice of new white migrants, many of whom were from the South. The study determined that Black respondents considered the lack of adequate housing the most important reason for the unrest among the African American population. The surveyors found that 73% of Black residents and only 3% of white residents lived in trailers; only 12% of Black residents, but 77% of white residents, owned homes; and 78% of Black families, but only 6% of white families, lived in one room. Almost 95% of Black people in Pasco lived east of the railroad tracks in old trailers or small shacks made of tarpaper, wood, and sheet metal. Most of this area had no electricity or plumbing — only outhouses and a few communal showers.34

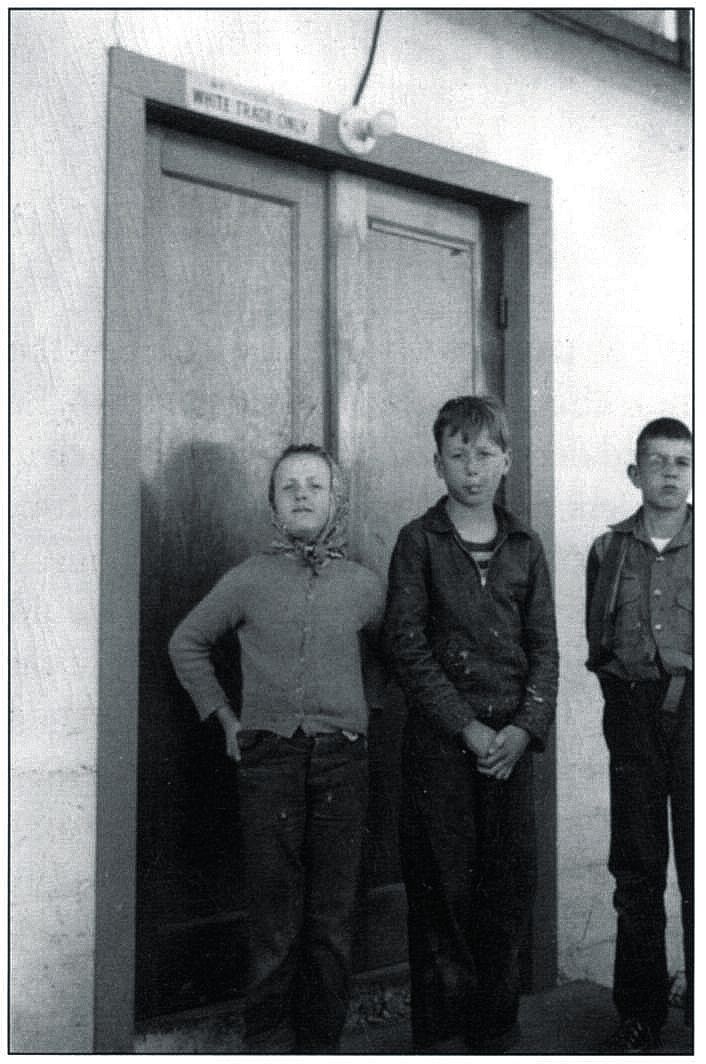

The WSC study also found that segregation in Pasco extended well beyond housing. The post office did not deliver mail east of the railroad tracks. No hotels or boarding houses accepted Black guests; only 2 of 12 restaurants in Pasco welcomed Black patrons (those that did not displayed ‘Whites Only’ and ‘No Dogs or Negroes Allowed’ signs); and the lunchroom at the bus terminal refused to serve African Americans. Only two barbershops would serve Black men, and both were operated by Black men; there were no beauty salons for Black women. Black customers were allowed in both movie theaters in Pasco but were restricted to either the balcony or the side aisle. This was not enough for one white female moviegoer, who complained to a WSC surveyor, "Sometimes when they turn the lights on, you find yourself sitting right in the middle of a bunch of n*ggers. You're just scared to death."35

Pasco law enforcement also continued to discriminate against Black residents. Though they constituted approximately 20% of the population, Black people represented 90% of those arrested for gambling; 81% of those arrested for illegal possession of liquor; 61% of those arrested for the all-inclusive crime of ‘investigation’; and 58% of those arrested for vagrancy.36 The racially discriminatory police practices established during the war clearly remained in force.

The WSC surveyors also queried Pasco residents about what they thought were the most important problems facing the city over the upcoming five years. Black residents overwhelmingly listed water supply and service as the most significant problem facing the city and racial discrimination as the second greatest problem. Whites listed crowded schools first, the presence of Black people second, and racial discrimination fifth.37 Living conditions were clearly what concerned African Americans most. The inadequate water supply and racial discrimination affected their daily lives and were, of course, inherently connected. White respondents did not live in areas where adequate water supply was a problem, nor did they face racial discrimination. But the Pasco schools were growing increasingly crowded, some with Black students. And local whites were now finding themselves frequently in contact with Black people as more and more African Americans arrived to work at Hanford.

In addition, the WSC surveyors probed people's attitudes about the arrival of African Americans to the area. They asked Pasco residents, Black and white, if the Black migration to work on the Hanford project had helped the country. An overwhelming majority (80%) of Black Pasco residents answered yes, but most whites (58%) responded that the Black migration had hurt the country. When asked how Black people in Pasco were treated, most Black respondents (78%) said they were treated unfairly; most whites (67%) thought Black residents were treated fairly.38 Segregation in Pasco was not limited to neighborhoods and businesses; its residents were divided along color lines in their perceptions of their lives and their communities, as well.

For some white Tri-Cities residents, though, the level of segregation that existed in the area was not enough. 35% of whites believed that no Black people should live in the area. In fact, according to one WSC surveyor, "Some whites were heard rather wistfully suggesting that they should have kept the Negroes out of Pasco entirely, as has been done by the neighboring city of Kennewick, which prides itself on being 'lily-white.'"39 As another surveyor noted, "In Kennewick, through unwritten pacts and laws of the business men and other local citizens, no Negroes were permitted to live within the city." The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer 1948 that racially restrictive covenants could not be enforced by state courts. In many cities, including Kennewick, the covenants had been "replaced by Voluntary agreements” between realtors and homeowners to refuse to sell or rent to African Americans.40

Though they had asked for the study, the cities did little to address any of its findings. National organizations did not directly address the WSC study, but they became involved in the challenge to Jim Crowism in the Tri-Cities after the war. In 1947, because of complaints made to her by Black residents, Pasco attorney Florence Merrick asked the Seattle affiliate of the National Urban League to study racial discrimination in the Tri-Cities. The League agreed and sent investigator Charles P. Larrowe to the Tri-Cities in September 1948.41

As part of his investigation, Larrowe interviewed the police chief of Kennewick. When Larrowe asked about residential segregation in that city, the chief responded, "If anybody in this town ever sells property to a n*gger, he's liable to be run out of town." Larrowe also investigated complaints of discrimination against Black employees at Hanford. The Atomic Energy Commission's deputy manager at Hanford informed Larrowe, "We have enough trouble here without having to cope with a Negro problem. We've got to think of our white majority, many of whom are southerners and would not stand for more Negroes here."42

Residents of the Tri-Cities also attempted to challenge racial discrimination and segregation by founding a local branch of the NAACP in 1948. The new Tri-Cities branch had 180 Black and white members. The branch focused on improving housing and living conditions, but it lacked influence. Some Black people refused to join for fear of repercussions from local whites. The branch had no office or regular meeting space. It made some attempts to increase employment opportunities and register Black voters but was largely ineffective in meeting those goals. By 1950, the Tri-Cities branch was essentially moribund, although Black locals, inspired by the Brown v. Board of Education decision, would revive it in early 1954.46

The struggles to establish a permanent civil rights organization in the Tri-Cities reflected both the mobility of the Black population and the strength of the local system of segregation which would persist, as would the challenges to it, well beyond the 1940s. The next generation of Black activists in the Tri-Cities, coming of age in the 1960s, would use the examples of those individuals and organizations that had challenged segregation in the 1940s to continue the fight.

Sources:

1. Washington State Board Against Discrimination, Report on the City of Kennewick, July 1963, box 5, Washington State Board Against Discrimination Records, Washington State Archives, Olympia (hereafter cited as WSBAD Records).

2. Tri-City Herald (Pasco, Wash.), May 24, 1963.

3. Josh Sides, "Rethinking Black Migration: A Perspective from the West," in Moving Stories: Migration and the American West, 1850-2000, Halcyon series, Vol. 23, ed. Scott E. Caspar and Lucinda M. Long (Reno, 2001), 185-21 1; Quintard Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle's Central District, from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era (Seattle, 1994); idem, "A History of Blacks in the Pacific Northwest, 1788-1970," Ph.D. dissertation (University of Minnesota, 1977).

4. Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Coleman, interview by Quintard Taylor, Dec. 8, 1972, Pasco, tape, Black Oral History Interviews, 1972- 1974 (ace. 78-3), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections, Washington State University Libraries, Pullman.

5. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940: Population, Vol. 2: Characteristics of the Population, pt. 7: Utah-Wyoming (Washington, D.C., 1943), 150-53; idem, Seventeenth Census of the United States, 1950, Vol. 2: Characteristics of the Population, pt. 47: Washington (Washington, D.C., 1952), 66-67.

6. James T. Wiley, Jr., "Race Conflict as Exemplified in a Washington Town," M.A. thesis (State College of Washington [Washington State University], 1949), 16.

7. Taylor, "History of Blacks," 219; Peter Bacon Hales, Atomic Spaces: Living on the Manhattan Project (Urbana, 111., 1997), 10; S. L. Sänger, Working on the Bomb: An Oral History of WWII Hanford, ed. Craig Wollner (Portland, Oreg., 1995), 68; E. R. Dudley, "Investigation of Civilian Defense Project at Hanford, Washington," June 1944, reel 5, pt. 15, series A, Papers of the NAACP, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

8. Franklin T. Matthias, "Diary and Notes of Col. Franklin Matthias, 1942-1945," Aug. 18, 1943, ace. 8113, U.S. Department of Energy Public Reading Room, Consolidated Libraries, Washington State University Tri-Cities, Richland

9. Wiley, 14.

10. Emmett B. Reed to Charles F. Schaefer, Nov. 10, 1943 (qtn.); Thurgood Marshall to Schaefer, Dec. 23, 1943, and to F. A. Stokes, Jan. 17, 1944; Stokes to Marshall, Feb. 5, 1944, all on reel 19, pt. 15, series A, NAACP Papers; Northwest Enterprise, Feb. 2, 1944.

11. Dudley.

12. Memo from Richland Human Rights Commission to Richland City Council, Aug. 6, 1969, Human Rights Commission folder, City of Richland History Collection, Richland Public Library, Washington; Tri-City Herald, Feb. 24, 2002.

13. Matthias, Aug. 29, 1943.

[14 included in the full article]

15. Dudley; Du Pont.

16. Wiley, 91-92 (qtn.); Dudley; Du Pont, 1:86-88; Kevin Boyle, "The Kiss: Racial and Gender Conflict in a 1950s Automobile Factory," Journal of American History, Vol. 84 (September 1997), 496-523.

17. Matthias, March 2, May 21, June 23, 1943; Tri-City Herald, Feb. 24, 2002.

18. Ray Henry, interview by Quintard Taylor, Dec. 8, 1972, Pasco, tape, Black Oral History Interviews.

19. Coleman interview; Du Pont, 1:84-85; Wiley, 14-15.

20. Dudley.

21. Coleman interview.

22. Taylor, "History of Blacks," 220-21.

23. Dudley. By the end of 1944, the Hanford branch of the NAACP boasted 292 members. See "naacp Branch Membership Report, 1944," reel 9, pt. 15, series A, naacp Papers.

24. Dudley.

25. Coleman interview; Henry interview.

26. Coleman interview.

27. Ibid.

28. Wiley, 14-16; Gordon R. Rutherford, "An Appraisal of the Adult Education Implications of a Community Survey," M.A. thesis (Washington State College, 1949), 6-7; Margaret Elaine Burgess, "A Study of Selected Socio-Cultural and Opinion Differentials among Negroes and Whites in the Pasco, Washington Community," M.A. thesis (Washington State College, 1949), 20.

29. See Mary L. Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (Princeton, N.J., 2000); and Manning Marable, Race, Reform, and Rebellion: The Second Reconstruction in Black America, 1945-1990 (Jackson, Miss., 1991), esp. chap. 2.

30. Charles P. Larrowe, "Memo on the Status of Negroes in the Hanford, Washington Area," April 1949, box 6, Records of the Office of the Chairman, AEC (David E. Lilienthal, 1946-50), Records of the Atomic Energy Commission (RG 326), National Archives, Washington, D.C; Washington State Board Against Discrimination, Second Semi-Annual Report, June 30, 1950, box 5, WSBAD Records (qtn.).

31. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Seventeenth Census of the United States, 1950, pp. 66- 67; Pasco Herald, Oct. 16, 1947.

32. Henry interview.

33. Rutherford, 3-13, 17-25; Burgess, 18-22.

34. Burgess, 7-8, 38-40; Wiley, 53-57, 60-61.

35. Burgess, 3, 21-22; Wiley, 62-66, 67 (qtn.), 81-82.

36. Wiley, 78.

37. Washington State University General Extension Service, A Community Survey of the Pasco -Kennewick Area, November, 1949 ([Pullman], 1949); Burgess, 48.

38. Burgess, 72-77.

39. Wiley, 53. See also Paschke, 58-59.

40. Burgess, 21, 22 (1st qtn.); Taylor, Forging of a Black Community, 179 (last qtn.), 180.

41. Florence Merrick biographical summary, n.d., Florence Merrick folder, Pasco History Collection, Franklin County Historical Museum, Pasco; Burgess, 6-7.

42. Larrowe.

[43–45 included in the full article]

46. "Branch Membership Report, 1950" and "New naacp Branch at Pasco to Hear N. W. Griffin," April 1948, both on reel 10, pt. 25, series A, NAACP Papers; Wiley, 74, 135-37; Minutes of the Executive Committee of the Northwest Area Conference of the NAACP, May 1954, folder 29, box 2, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Seattle Branch, Records 1950-1968, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle.

Robert Bauman is an assistant professor of history at Washington State University Tri-Cities. Bauman's research interests are race in the American West, poverty, and public policy. His forthcoming publications include an article in the Journal of Urban History on the War on Poverty in Los Angeles.

Main image: A civil rights protest in 1963 in Kennewick, Washington. Credit: Franklin County Historical Society Collection