Are you concerned about climate change, but are not sure what to do about it? Do you feel bad about the greenhouse gas emissions you personally generate as you go about your life? While climate policies are needed to drive everyone to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, reducing your own emissions is how you ‘walk the talk’, giving your advocacy credibility and making you feel better about your own contributions to global warming. But your efforts must be effective.

A relevant measure of your climate impact is your personal carbon footprint—the amount of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases (expressed as equivalent CO2) emitted due to your purchases and activities.

In this and the column next month, I’m going to describe how to estimate your personal carbon footprint, how to reduce it, and what to do about the carbon emissions you haven’t eliminated.

Let me begin by stating that we should not obsess about our carbon emissions. Yes, most of us can reduce our carbon footprint considerably without sacrificing the activities we enjoy, but we’ll never be able to reduce our carbon footprint to zero. Indeed, we can’t even breathe without putting carbon dioxide into the air. But we can all do better than we’re doing, and if we don’t try, then we can’t credibly ask others to do so.

The first step is to take an inventory of your carbon footprint. Numerous useful sites, such as terrapass.com or carbonfootprint.com, and apps, such as LiveGreen, are available. These account for the particular mix of electrical production sources where you live (which varies considerably from state to state and even PUD to PUD), how you heat your home, the gas consumption of your modes of transportation, your diet, and the lifecycle of the products you use.

I encourage you to get one of these tools and use it to inventory your household carbon footprint. That will form the baseline against which to compare changes in your home, transportation, diet, and other consumption habits.

For comparison with your own carbon footprint, the U.S. average personal carbon footprint is 16 metric tons of CO2-equivalent greenhouse gases per year per person, and the global average is 5 metric tons (see nature.org). If yours is higher than the global average, you might feel motivated to reduce it. Here’s how.

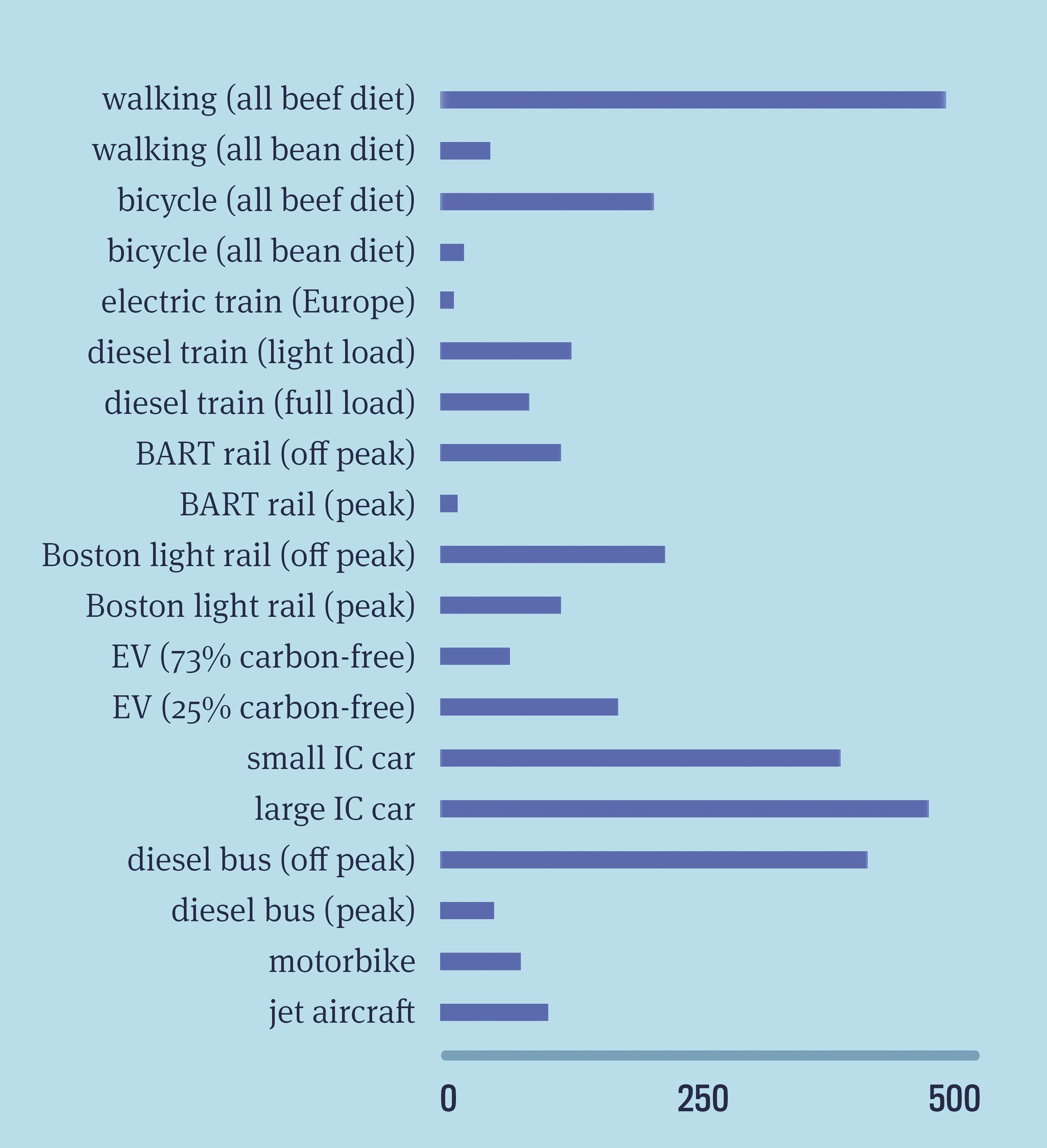

A large fraction of your carbon footprint is likely from transportation. To help you identify ways to reduce your carbon emissions from transportation, I’ve calculated the grams of CO2-equivalent greenhouse gases per kilometer per person for a variety of modes of transportation.

Some of the more surprising results I encountered while making these calculations are that:

- Emissions from driving a small internal-combustion passenger car alone are almost four times higher than flying in a full jet aircraft

- Even when walking, consuming an all-beef diet creates more CO2 than driving a car

- Walking or bicycling with an all-bean diet creates one tenth as much CO2 as an all-beef diet

Some of the lessons we can glean from looking at transportation and diet are that flying has a large impact on a person’s carbon footprint primarily because one can travel so much faster and farther than any other mode of transportation, and that choosing vegetables over beef can reduce your transportation emissions substantially if a lot of your miles are from walking or bicycling. A beef-free diet will also reduce your emissions when you aren’t using those calories for transportation. And, of course, replacing your internal combustion vehicle with an EV will reduce your carbon emissions substantially since more than 90% of our electricity is carbon-free. Overall, bicycling on a vegetarian diet is one of the lowest-carbon modes of transportation.

To reduce your commuting miles, either try to live close to your school or job, or work remotely from home, if those are options for you. If you travel a lot for your job, consider using teleconferencing rather than traveling. But a lot of us have had to do that lately because of the pandemic, haven’t we?

If your home is older than 20 years, you can likely reduce your emissions substantially by electrifying your heating system and improving your home’s energy efficiency. A home energy audit by your utility can identify leaks and tell you whether more insulation will help. Some states and municipalities offer programsto support electrification of building heating systems. Washington State is not one of them. Legislation requiring electrical heating in new buildings is pending in the Washington State legislature, but no funding is available to overcome barriers to electrification of heating existing buildings. Funding is particularly important for rented buildings, because owners lack incentives for costly improvements that primarily benefit tenants.

A surprisingly large fraction (roughly half) of consumer emissions occur when the products they purchase are manufactured. You can reduce your emissions and your waste by reusing items as many times as possible, and repairing them when they break instead of replacing them. When you purchase items, choose brands that are durable, not disposable.

All of these actions can save you money. But then there are those vacations across the country or abroad. Rather than give them up, can you compensate for your carbon emissions with carbon offsets?

Next month you’ll learn about the challenges of ensuring that carbon offsets really make a difference in reducing emissions or removing carbon from the atmosphere.

Sources

https://caloriesburnedhq.com/calories-burned-walking/

https://caloriesburnedhq.com/calories-burned-biking/

http://www.foodemissions.com/foodemissions/Calculator.aspx

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/4/2/024008/pdf

https://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/images/2015/11/vehicles-m-emissions-map-with-notes.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Environmental_impact_of_transport

Photo by Marcin Jozwiak on Unsplash