I remember my mom telling me about how my father would come home from the orchards drenched in pesticides. This was the early ‘80s in the Yakima Valley, when just about any chemical was legal to use, and protection for farm workers was limited. He might get a flimsy mask if he was lucky. That’s it.

Years later, when he was diagnosed with melanoma cancer in his mid-forties, we knew what we believed had caused it. Cancer doesn’t run in his side of the family. He’s the only one, ever. My mother believed immediately that the pesticide exposure was the cause. He battled that cancer until 1999, when he died at just 45 years old, leaving behind medical debt, a grieving family, and questions about workplace safety.

My father’s story isn’t unique. Many families here in the Lower Yakima Valley have similar experiences with injury, illness, and death related to agricultural work. We’ve been told that the stench of manure at our children’s graduations is just how things are. That brown, foul-tasting municipal water in Mabton is acceptable because the contaminants aren’t “regulated.” That workers who develop asthma must pay $400 – $600 monthly out of pocket for medication because many agricultural employers don’t provide healthcare.

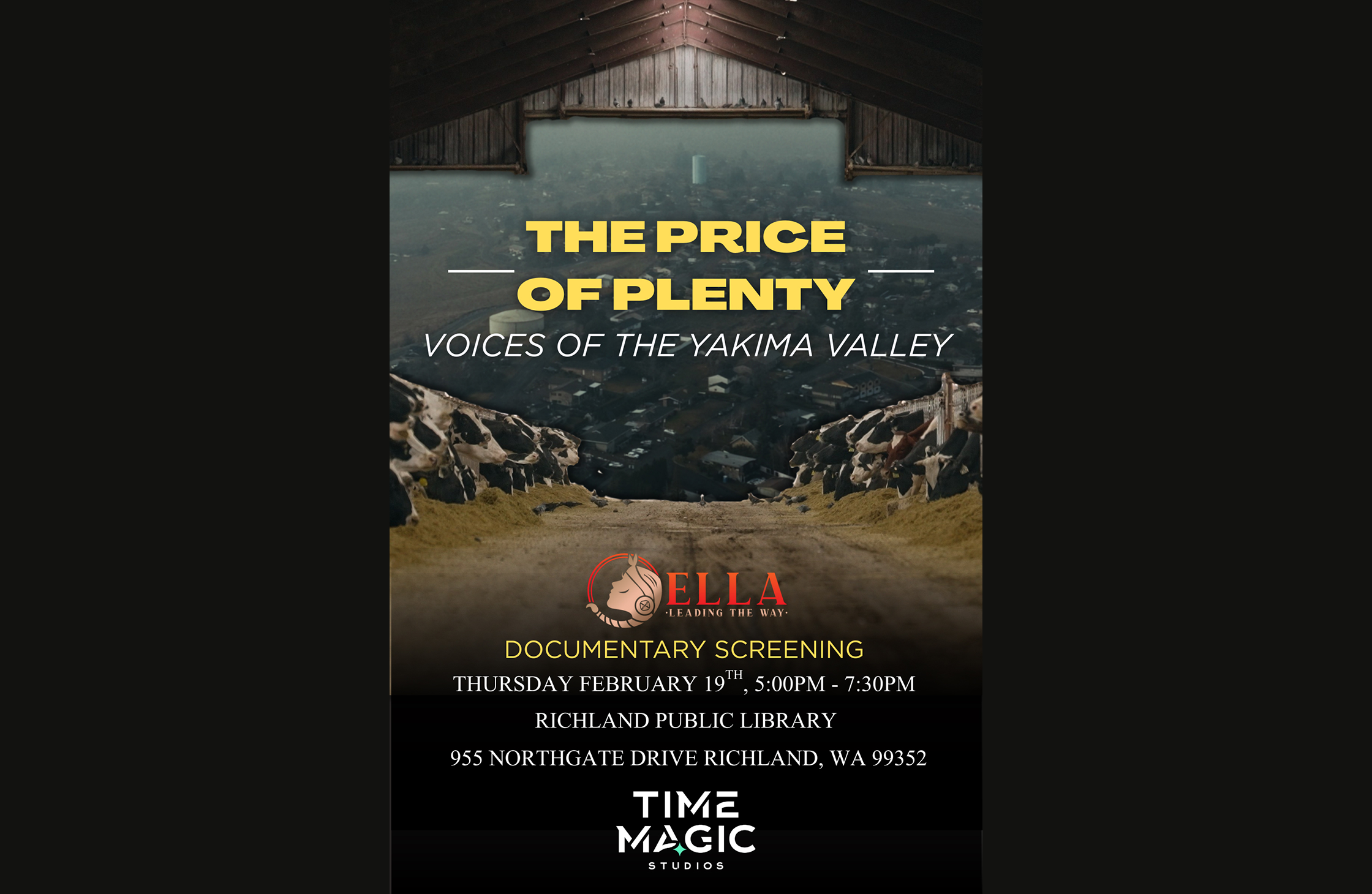

This is why we made The Price of Plenty: Voices of the Yakima Valley.

Living surrounded by CAFOs

Our documentary opens with Teodora’s story. She lives in Outlook, surrounded by concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), large dairy operations with thousands of cows. Her well water tests above safe nitrate levels. She can’t drink it. She can’t cook with it. She’s not even sure if it’s safe to grow vegetables with it anymore.

She’s one of over 380 families in our area dealing with contaminated wells, some testing at nine times the safe drinking limit. And it’s not just the water. According to the EPA, our region ranks in the 95th percentile for air pollution in the country. A 2025 Johns Hopkins study on swine CAFOs — as well as a much earlier study of Yakima Valley in 2011 — found that particulate matter can travel up to three miles on the wind.

The University of Washington has documented a relationship between ammonia levels and impaired lung function in asthmatic children in our area. You don’t have to work in the industry to be affected by it. You just have to live here.

The facts we document

In our documentary, environmental attorney Charlie Tebbutt presents data from two decades of litigation. His expert analysis shows that 99.35% of nitrogen loading in our groundwater comes from large dairies. These are court findings, based on extensive testing and analysis.

But The Price of Plenty isn’t just about numbers. It’s about the fertilizer worker who was burned on over 80% of his body by chemical exposure, and was then fired. It’s about Randy Vasquez, who drowned in an unprotected manure lagoon in 2015. It’s about farmworkers who develop asthma and must pay for their own medication because their employers don’t provide health insurance.

One gentleman in our film spends over $400 a month on asthma medication, out of pocket, with no insurance, for a condition he attributes to working in the ag industry. This is still happening today, thirty years after my father worked in those orchards.

Industry and accountability

The ag industry and dairy industry are important economic drivers in our region, and they do provide jobs. But there are real costs that aren’t accounted for in the market price of agricultural products. When wells are contaminated, when workers get sick, when families struggle with medical debt, who pays those costs?

These are questions we need to ask. When do we enforce the regulations that already exist? What responsibility do employers have to protect their workers’ health? What do we owe the families who live near these operations?

That’s why we worked with scientists like Ron Sell and Jean Mendoza of Friends of Toppenish Creek, who have conducted over 15 years of independent water quality monitoring. We’re making the scientific documents we’ve gathered available publicly, because we believe people deserve access to this information.

Another way Is possible

We don’t just document problems; we present alternatives. We visited Cooperativa Tierra y Libertad in Everson, Washington, a worker-owned farm practicing sustainable, regenerative agriculture. The families who work the land have access to healthcare and are building equity as owners.

Our people have deep connections to the earth and to agriculture. But we need to be able to imagine different ways of farming — approaches that prioritize both environmental health and worker dignity.

Join us

We’re bringing The Price of Plenty to the Tri-Cities with a screening on February 19 at the Richland Public Library from 5 – 7:30pm. Then, on April 18 from 5 – 8pm, we’ll screen at the Social Justice Film Festival with a panel discussion following.

Come watch. Come ask questions. Come be part of the conversation about what’s possible when we prioritize public health alongside economic development, when we enforce existing regulations, when we talk openly about the full costs of our food system.

Maria Fernandez is the Executive Director and founder of ELLA (Empowering Latina Leadership and Action) and co-director of The Price of Plenty: Voices of the Yakima Valley.

References:

- pure.johnshopkins.edu/en/publications/swine-production-intensity-and-swine-specific-fecal-contamination

- pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3184623

- sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1438463919306637

- charlietebbutt.com/cafos.html

- friendsoftoppenishcreek.org

- cascadecooperatives.coop/cooperativa-tierra-y-libertad

- socialjusticefilmfestival.org