Damage at Multiplaza Las Palmas shopping center, Puerto Marqués. Images of the aftermath of hurricane Otis, Acapulco, Guerrero, Mexico. / ProtoplasmaKid, CC BY-SA 4.0

This article is bilingual! Scroll down for the English translation.

“Les llueve sobre mojado”. No hay otro dicho que le quede mejor al estado de Guerrero. Acapulco todavía no se recuperaba del huracán Otis del 24 de octubre de 2023, cuando casi un año después, el 23 de septiembre de 2024, el ciclón tropical John lo golpeó nuevamente. El primero fue de categoría cinco y el segundo de categoría tres, y ambos coincidieron en algo: trajeron mucha agua, muerte, destrucción y destaparon una cloaca llena de corrupción e incompetencia. La naturaleza ratificó lo que todos ya sabíamos: inseguridad disparada, inaplicabilidad de la ley en materia de construcciones, cifras dudosas en el número de víctimas y el abuso de muchas personas al recibir los apoyos.

Pero, como dijo Jack el Destripador, vámonos por partes.

El huracán Otis dejó cuantiosos daños materiales, centenares de damnificados, el 80% de la zona hotelera inhabilitada y, oficialmente, 50 fallecidos y 30 desaparecidos. Meses después, cuando las aguas turbias parecían calmarse y con la ilusión de que pronto volveríamos a ver a la Virgen desde la lanchita de fondo de cristal (con todo y sus fugas), el puerto fue sorprendido por el ciclón John. Este provocó que en solo cuatro días cayera el 80% de la lluvia de todo un año. Así es, querido lector: ¡llovió sin parar durante cuatro días! Los ríos se desbordaron, hubo inundaciones, daños materiales y una cifra oficial de 29 fallecidos y cuatro desaparecidos.

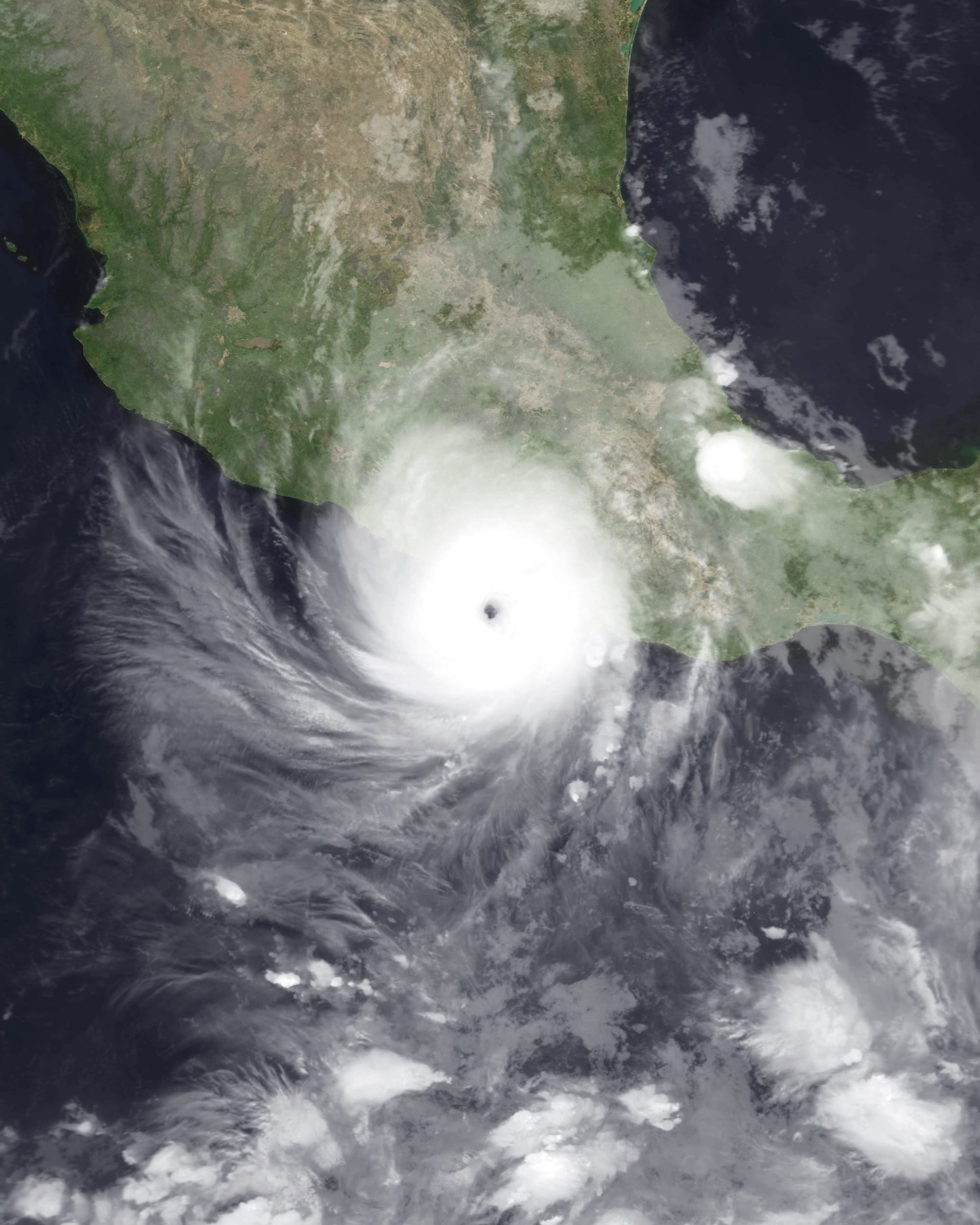

Pasemos a la pena ajena. Con el huracán Otis, el Centro Nacional de Huracanes de Estados Unidos advirtió 21 horas antes que podría golpear Acapulco con categoría cinco, pero en México no se tomaron medidas. Nos vendieron la idea de que el huracán estaba siendo monitoreado, pero que inesperadamente cambió su dirección hacia Acapulco. Entendemos que los huracanes no siempre son predecibles y que, a veces, amenazan con llegar con toda su fuerza y luego se degradan o desvían, pero, independientemente de eso, siempre hay que extremar precauciones y tener listos protocolos preventivos, más aún cuando se vive en una costa.

Ambos fenómenos dejaron al descubierto una vergonzosa incompetencia en el control de datos. No hubo un censo veraz y oportuno. La cifra oficial de víctimas no coincidía con los testimonios de los habitantes, quienes hablaban de más de 350 muertos solo con el huracán Otis, y sobre los desaparecidos, mejor ni hablar.

Lo que sigue es de vergüenza: el lado buitre que un sector de la población mostró en medio de la tragedia. La rapiña y los asaltos estaban a la orden del día. Saquearon tiendas, centros comerciales, vandalizaron autos, y delincuentes armados despojaron a muchas personas de las pocas pertenencias que apenas habían logrado rescatar.

Respecto a los apoyos económicos que el gobierno brindó a los afectados (desde siete mil quinientos hasta cuarenta mil pesos), algunos vivales recibieron el dinero hasta en cuatro ocasiones, cuando se suponía que era un apoyo único.

En cuanto a los hoteles inhabilitados, al recorrer la zona se aprecia que solo queda el esqueleto de muchos edificios, aunque algunos (pocos) siguen en pie, casi intactos. No hace falta ser arquitecto o experto en la materia para entender lo que pasó, basta con hablar con cualquiera de los habitantes para confirmarlo. Los hoteles que se desplomaron como cajas de cartón fueron construidos con materiales baratos para optimizar recursos. Estaban forrados, por ejemplo, con plafón en lugar de cemento y pegados con materiales de mala calidad. Se ignoró completamente el Reglamento de Construcciones del Municipio, que establece la obligación de usar materiales adecuados para evitar tragedias. En cambio, las construcciones que sí resistieron el embate del meteoro fueron hechas con materiales adecuados y mayor cuidado.

Después del ciclón John, ayudamos en algunas viviendas situadas junto al río La Sabana, cerca de la laguna de Tres Palos (lejos de la zona hotelera), en una colonia sin pavimentar. El agua se salió de su cauce, alcanzó niveles superiores a los dos metros y, al retirarse, dejó un panorama desolador. Capas de lodo de más de veinte centímetros (dentro y fuera de las casas), enseres y autos inservibles, animales muertos, víboras e insectos (sobre todo arañas y alacranes) y, lamentablemente, dos cadáveres de adultos mayores. Sacábamos el lodo de las casas con palas y carretillas; la mayoría de las casas eran humildes, aunque algunas eran ostentosas, y no tenían electricidad ni agua. Al retirarnos, casi al oscurecer, vi a una muchachita descalza, bañada en sudor, que intentaba sacar con sus propias manos un ventilador atrapado en el lodo de su tejabán. Le regalé botellas de agua y le ayudé con el ventilador. Después de decirme su nombre, María, me reveló historias de terror. Me contó que en Guerrero, muchas personas no tienen acta de nacimiento ni identificación y que el gobierno local, para contabilizar a los muertos, se basaba en el número de funerales, pero que mucha gente fue enterrada en fosas sin notificar a las autoridades, sin protocolos legales; y eso ayuda a entender una de las causas por las que las cifras oficiales son poco creíbles. Finalmente, confesó que la zona era peligrosa y que muchos de los habitantes eran invasores.

Moraleja: Si invades (aunque, de preferencia, no lo hagas), no construyas al lado de un río, ya que después de la tormenta te estarán diciendo: “Acuérdate de Acapulco, María bonita.”

English translation:

“When it rains, it pours.” There is no saying more fitting for the state of Guerrero. Acapulco was barely recovering from Hurricane Otis on October 24, 2023, when, almost a year later on September 23, 2024, it was hit by Tropical Cyclone John. The first was category five and the second was category three, but they shared one thing in common — both brought massive rainfall, death, and destruction, and uncovered a cesspool of corruption and incompetence. Nature confirmed what everyone already knew: there was rampant insecurity, lax enforcement of construction laws, questionable death tolls, and the abuse of aid by some individuals.

But, as Jack the Ripper said, let’s take this one part at a time.

Otis left significant material damages, hundreds displaced, 80% of the hotel zone out of service, and (officially) 50 deaths and 30 missing persons. Months later, just as the murky waters seemed to be settling, and with the hope that we’d soon be seeing the Virgin from the glass-bottom boat (leaks and all), the port was struck again by Cyclone John. In just four days, it dropped 80% of the typical annual rainfall. That’s right, dear reader, it rained continuously and heavily for four days! Rivers overflowed, there was flooding, there were material damages, and there was an official toll of 29 dead and four missing.

And now we move on to the unfortunate second act. With Otis, the U.S. National Hurricane Center warned 21 hours prior that it could hit Acapulco as a category five hurricane. But in Mexico, no precautions were taken. We were sold the idea that the hurricane was being monitored, but that it had unexpectedly changed direction toward Acapulco. While we understand that hurricanes can be unpredictable and that sometimes they threaten to arrive in full force only to weaken or change course, precautions should always be taken and preventive protocols ready, especially when living on the coast.

Both disasters (this one and later, Cyclone John) revealed a shameful level of incompetence regarding data management. There was no accurate and timely census. The official death toll conflicted with residents’ accounts, which mentioned over 350 deaths from Otis alone — and we can’t even get started on the missing persons.

The shame continued with the vulture-like attitude shown by certain people in the midst of tragedy. Looting and robberies were rampant. Stores, shopping centers, and cars were vandalized, and armed criminals robbed many people of the few belongings they had managed to save from their flooded homes.

Regarding the financial aid provided by the government to those affected (ranging from 7,500 to 40,000 pesos), some savvy individuals magically managed to receive the funds up to four times, despite it supposedly being a one-time payout.

As for the hotels that were disabled, one can see when visiting the area that many buildings are mere skeletons now. But some others (though few) remain standing, almost intact. You don’t need to be an architect or expert to understand what happened; just talk to any local, and you’ll find out. The hotels that collapsed like cardboard boxes were built with cheap materials to cut costs. For example, they were clad with plaster instead of cement and slapped together with ‘shoddy’ adhesive, as my grandmother would say. They flagrantly ignored the municipal building code, which clearly mandates the use of appropriate materials to prevent tragedies. Meanwhile, the structures that withstood the storm’s impact were built with more care and quality materials.

After Cyclone John, we helped out in some homes situated near the La Sabana river, close to the Tres Palos Lagoon (far from the hotel zone) in an unpaved neighborhood. The river overflowed, reaching levels over two meters high; and when it receded, we saw the desolate scene it left behind: layers of mud over 20 centimeters thick (both inside and outside the houses), ruined appliances and cars, dead animals (mostly snakes, insects, spiders, and scorpions), and, tragically, the bodies of two elderly individuals. We used shovels and wheelbarrows to remove the mud from the homes; most of them were humble, though there were a few more lavish ones, and none had electricity or running water.

As we left, near dusk, I saw a young girl, barefoot, covered in sweat, trying to pull a fan from the mud in her shack with her bare hands. I gave her some bottles of water and helped with the fan. After telling me her name, María, she shared some chilling stories. She said that in Guerrero, many people don’t have birth certificates or IDs, and that local authorities were tallying deaths based on the number of funerals. However, many people were buried in unmarked graves without notifying authorities or following legal protocols. This helped me understand one reason why official numbers are so hard to believe. Finally, she admitted that the area was dangerous and that many residents were squatters.

The moral of the story: If you’re going to squat (though it’s best not to), don’t build next to a river, because after the storm, people will be telling you, “Remember Acapulco, Beautiful María.”

Originario de la Ciudad de México, Oscar Taylor cuenta con estudios superiores en Derecho y Administración Pública. Ha sido catedrático en diversas instituciones educativas de México y se desempeña como Disc Jockey profesional desde 1988 y servidor público desde 1996. Oscar fue locutor de Grupo Radio Fórmula Monterrey de 2012 a 2015, y en 2018 fue galardonado con la Palma de Oro por el Círculo Nacional de Periodistas de México. Ha ganado diversos Concursos de Calaveras literarias. Oscar es autor de la obra literaria postapocalíptica ÁNIMA, y es el creador del podcast “El Búnker de Oscar Taylor”.

Originally from Mexico City, Oscar Taylor has advanced degrees in Law and Public Administration. He has been a professor at various educational institutions in Mexico and has worked as a professional Disc Jockey since 1988 and a public servant since 1996. Oscar was a speaker for Grupo Radio Fórmula Monterrey from 2012 to 2015, and in 2018 he was awarded the “Palma de Oro” by the National Circle of Journalists of Mexico. He has won various literary 'Concursos de Calaveras' (contests of traditional satirical writing in verse). Oscar is the author of the post-apocalyptic literary work ÁNIMA, and is the creator of the podcast El Búnker de Oscar Taylor.

Este artículo es presentado por El Vuelo Informativo, una asociación entre Alcon Media, LLC y Tumbleweird, SPC.

This article is brought to you by El Vuelo Informativo, a partnership between Alcon Media, LLC and Tumbleweird, SPC.