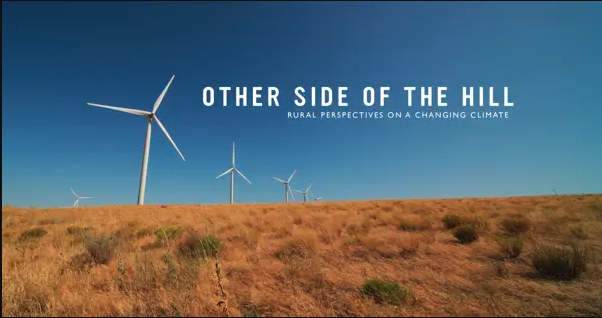

In bizarre and scary times like these, I’ve found that a little bit of good news goes a long way. So I was pleased to discover that a newly-released documentary called Other Side of the Hill offers lots of it on two topics that may surprise you: climate change and politics. Specifically, the film explores how rural Oregon communities have successfully adapted to a changing climate, and it directly addresses the ‘east/west’ divide unique to Oregon and Washington.

If such a film appeals to you, then you’ll want to take note of a free, virtual screening happening next month, hosted by the Tri-Cities chapter of Citizens’ Climate Lobby. We will begin by watching the film (run time: approximately 30 minutes) and then participate in a Q&A session with some of the producers and film subjects, who have graciously offered to join us. Participants are encouraged to ask questions. I asked James Parker, the film’s director, some questions of my own, and he was kind enough to answer them.

What inspired your team to undertake this project? What made you choose Eastern Oregon, specifically?

James Parker: The film was inspired by a frustration in the breakdown of communication in climate discussions in the Oregon legislature—specifically around H.B. 2020. This led myself and a group of rural Oregon landowners, composed of both Republicans and Democrats, to dig deeper into some of the rigid definitions being used to describe rural Oregonians when it comes to climate change. There seemed to be this myth of the monolithic rural conservative which cast a broad stroke over the entire Eastern part of the state.

We set out on a mission to ask questions and listen to folks in Eastern Oregon to understand if A) they felt like climates were changing, and B) what was being done to address those changes. As you’ll see in the film, we discovered tremendous stories of hope and innovation all across rural Eastern Oregon, as well as a desire for more collaboration.

The Cascade Mountains divide Oregon and Washington geographically, as well as politically. There is a perceived ‘east/west’ and ‘rural/urban’ divide that is tough to overcome. I’ve witnessed both sides weaponize and exaggerate this divide for their own gains. Do you think the divide is as real as we perceive it to be?

JP: It’s clear the political divide has grown deeper between urban and rural communities in Oregon, but I think it’s only superficially covering up what we share. If we can sit down at a table and listen to one another, and as Jim Walls from Lake County says, “disagree but not disagree disagreeably,” I think it’s possible for us to find those shared values and begin to collaborate again.

Another element to bring rural and urban communities together is acknowledging the interconnectedness of it all. Nils Christopherson and Matt King from Wallowa Resources described it really well: rural economies produce the fuel and resources that power urban economies, and urban economies produce the demand for rural goods.

It’s obviously much more complex than how I just stated it, but the point is that we rely on one another. And if one side suffers, the other does as well.

I think it’s of critical importance that we work to understand one another. And respect our differences. And listen to one another. And I think in many ways, that’s what this film is about.

The film highlights ways in which rural Oregonians are working to mitigate climate change, and it’s clear that the people interviewed care deeply about this issue. Did they mention any obstacles they encountered as they worked to find solutions?

JP: I know each of the solutions we highlight in the film came at great expense and hardship from the folks spearheading their implementation. But beyond the logistical challenges, we discovered one of the primary challenges can be remaining politically neutral when addressing things like climate change, renewables, and forest practices in conservative rural communities. It seemed really important that solutions come from the ground up, from folks who know the nuances of a community, and not from outside organizations.

Another theme we heard more than once was that when solutions are economically, culturally, and ecologically beneficial, they are generally supported in the community.

An example would be in Wallowa County, where Matt King and Nils Christopherson are working to encourage more landowners and industries in the region to embrace the stewardship economy model. They are acknowledging the community’s dependence on the land for livelihoods, but also ensuring that other values of the forest are taken into account to preserve the long-term health and sustainability of the whole system.

And in Lake County, Jim Walls and Nick Johnson from LCRI have implemented many triple-bottom-line solutions like large scale solar and geothermal projects. While these solutions alone may not address climate change, the point is that there’s a lot of low hanging fruit out there that we can jump on right now.

Based on your experience, how can rural climate-change activists best win over the support of their neighbors?

JP: I think the best approach is to listen and to re-frame some of the language. The words ‘climate change’ have come to carry so much baggage for a lot of folks. Perhaps you can achieve more when you just focus on the solutions and benefits.

Wallowa Resources, one of the groups we feature in the film, completed a study covering seven counties in Eastern Oregon. They found that over 80% of citizens surveyed understand that the climate is changing, and understand that the fire season is getting longer, and that we have hotter and drier summers. But less than 50% attribute that change to human causes. So the approach they are taking is to focus on what those hotter and drier summers will mean to folks, and how we can start to address some of these changes to preserve this land we love and make sure it’s around for our children.

Did anything happen while filming that surprised you?

JP: I live in an urban area and so had a considerable amount of trepidation before we started filming in some of the rural communities we did. I was so pleasantly surprised by how kind and welcoming folks were and how quickly I made friends with almost everyone we interacted with. It was a reminder for me of how much more we have in common than in difference.

It’s tough to talk about something like climate change if the parties involved disagree—on the threat level, on a course of action, or even if climate change exists at all. CCL recommends listening to what ‘the other side’ has to say, and using that as a way to learn what values are most important to them. It’s clear that a lack of listening to the other side has been a problem, on both the federal and state levels. What should progressives do differently if they truly want rural communities as climate allies?

JP: I would echo CCL’s recommendation: listen. The more understanding and compassion we can have for each other, the more common ground we will find and be able to build from. I’d also encourage progressives to look more often to their rural conservative neighbors for new ideas and solutions around climate change. There’s a lot of incredible work happening in places that progressives might not typically look. Having an open mind to ideas from the ‘other side’ can help us all better address the issues we’re facing.

If these questions pique your interest, please consider joining us and asking a few of your own!

Other Side of the Hill will have a screening on Friday Feb 5, 2021, at 7:00 P.M. Pacific Time.

Here are some ways to join the event:

- Via Facebook event

- Via Zoom (computer application)

- Meeting ID: 960 328 0404

- Passcode: tricities

Special thanks to James Parker, who assisted me in organizing this screening, and to Emily Whittier, who recognized CCL’s potential interest in this film and made the necessary introductions.