This past school year, I had the pleasure of working as a paraeducator at one of Richland’s elementary schools. Paraeducators (or “duties,” as the students call us) assist with a wide range of day-to-day operations within the school. One of my daily roles was helping fifth-grade Safety Patrol students with their crossing-guard responsibilities.

Even if you’ve been out of school for a while, it’s likely that you’re familiar with Safety Patrol to some extent. You’ve probably seen these students at work as you drive by our local elementary schools; if you’re a parent or teacher, you may know some of them. Maybe your own son or daughter has served in this role, or will want to do so when they are old enough.

If you don’t often interact with Safety Patrollers, you might be surprised to find, as I was, how unimpeachably professional they are, and how gamely they carry out an unglamorous and sometimes dangerous job. If it sounds like I’m exaggerating in reference to eleven-year-olds — well, I’m not. Every day, for 180 days, these student volunteers arrived to school early and stayed late. They handled bad weather (and even worse driver behavior) with aplomb. Although I was there to supervise them, they seldom needed it.

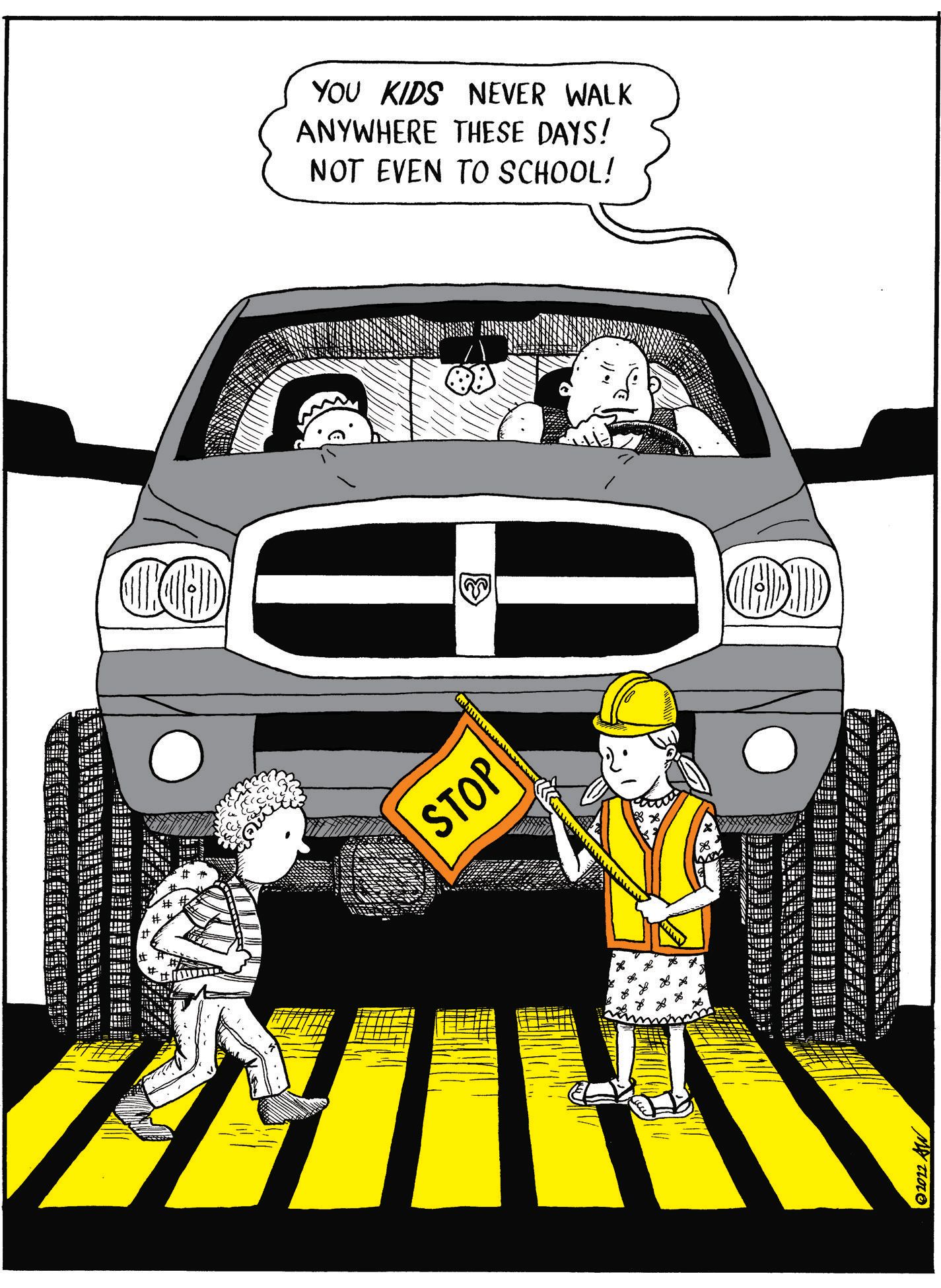

Before I worked at the school, I only ever encountered Safety Patrol students from the driver’s seat, and my opinion of them could be summed up in one word: annoyance. You are undoubtedly familiar with this feeling — unbidden, surprisingly forcible annoyance stoked by life’s minor inconveniences. And what a tremendous inconvenience it is to be delayed, even for a moment, by a flag-waving child in a yellow vest!

I admit this feeling because I suspect I’m not alone in harboring it. After all, as drivers, we exist as the centers of our own steel-caged universes. We expect — no, demand that the world outside be organized to our maximum benefit at all times. When this fails to occur, we don’t like it, and we sometimes behave badly in response. While working with the Safety Patrol students, I saw such behavior many, many times; it always amazed me how, moments after delivering their own child safely to school, parents seemed so eager to run over somebody else’s.

Thankfully, none of my students was hurt this year, though the possibility is very real. The NHTSA’s most recent annual fatality report noted that pedestrian deaths increased by 13% in 2021, while fatalities involving “at least one big truck” increased by the same percentage. This latter point is worth examining. According to Streetsblog USA: “The probability of death for a pedestrian who gets hit by a larger-than-average vehicle is 3.4 times higher than one who gets hit by a smaller passenger car.” This is because a larger vehicle strikes at a higher point on a person’s body, where more critical injuries are sustained.

This is especially true for children. One of the things that surprised me most about my Safety Patrol students was just how small they were; though the fifth graders are the oldest students at the school, they’re still little kids. Even with a bright yellow hardhat, most stood below the hoods — and sight lines — of the full-size trucks that swarmed the school zone during pick-up and drop-off. Without their fluorescent flags, the students were invisible.

This invisibility is no accident. It is a choice made by millions of drivers who mistakenly believe that larger, heavier cars are always safer. It is encouraged by auto manufacturers, who design and market increasingly supersized vehicles. And it’s aided and abetted by a federal agency that refuses to account for pedestrian safety, through their continued failure to implement agreed-upon international safety standards. The invisibility of our children is a literal manifestation of a figurative action; the forced disappearance of anyone who can’t (or won’t) join this insane and unsustainable vehicular arms race: children, cyclists, motorcyclists, the homeless, and drivers of smaller cars.

So, what can we do? Although much needs to be done at the regulatory level, there are concrete actions that you can take today. If you’re able to walk, bike, or take the bus instead of driving, even occasionally, this decreases traffic and makes your chosen activity safer for everyone. When your city solicits public comment on road and infrastructure changes, be a vocal supporter for slower, safer streets. When choosing your next car, try to strike a balance between size and safety; a significant contributor to road fatalities is the size differential between cars that hit each other. More drivers choosing smaller cars will make the roads safer for everybody.

All of these actions are valuable, but the most important thing you can do is to simply SLOW DOWN. People will excuse you for showing up late, but will be less forgiving if you kill somebody. So follow the speed limit, especially in school zones. Normalize driving slower as conditions dictate, such as in bad weather, in traffic, and in residential neighborhoods. And the next time a Safety Patroller in a hi-vis vest blocks your path, please try to model safe driving behavior for them. They are in desperate need of good examples.

Sources:

- Krisher, Tom, and Hope Yen. “Nearly 43,000 people died on US roads last year, agency says.” AP News. 17 May 2022.

- Wilson, Kea. “Vehicle Safety Assessments Don’t Protect Pedestrians.” Streetsblog USA. 28 April 2020.

- Yarris, Lynn. “Is Bigger Safer? It Ain’t Necessarily So.” Science Beat. Berkeley Lab, U.S. Dept. of Energy. 26 August 2002.

- Orlove, Raphael. “The Trucks Are Too Big.” Jalopnik. 15 December 2020.

- Marquis, Erin. “NHTSA Isn’t Doing Enough To Protect Us From Giant Trucks.” Jalopnik. 28 April 2020.

- Courtney, Will S. “Are Large Cars Safer Than Small Cars? Not Necessarily, Study Finds.” The Drive. 8 May 2017.

Adam Whittier is a cartoonist in Richland who refuses to join the Vehicular Arms Race. Follow him on Instagram at @whittier_comix