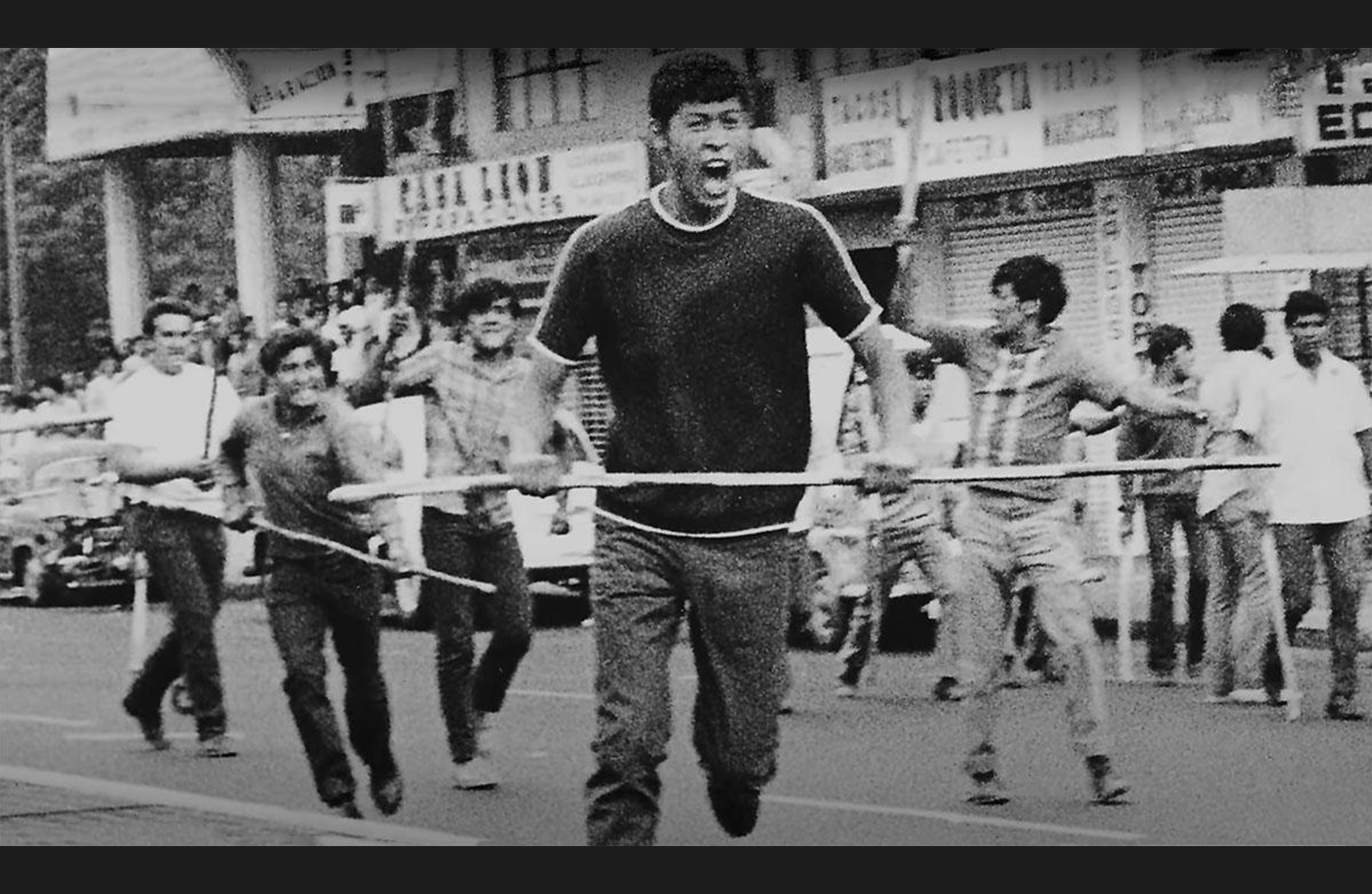

Miembros del grupo paramilitar Halcones atacan a estudiantes el 10 de junio 10, 1971. (Members of the Halcones paramilitary group attack students on June 10, 1971.) http://todosloscaminoshaciati.blogspot.com

This article is bilingual! Scroll down for the English translation.

“Y el olor de la sangre mojaba el aire, y el olor de la sangre manchaba el aire”. — Fragmento de poema náhuatl.

El viento arrastraba una manta blanca de varios metros de largo sobre la calle. Su mensaje, ya intrascendente, era incomprensible, y sus portadores —valerosos hasta hacía unos momentos— huían presas del pánico. Había gritos, estruendo, humo, fuego, golpes. Había sangre. Podía olerse, podía sentirse, podía verse. Era odio, era demencia, era guerra. La intolerancia y la soberbia se percibían como nubarrones negros sobre los edificios, oscureciendo un día apacible y cálido.

Los hombres que portaban las armas se mostraban frenéticos, iracundos, enloquecidos por la fuerza, el poder y la impunidad. Los gritos de dolor, los reclamos y los llantos no podían ser procesados por sus mentes adiestradas. Tampoco eran capaces de distinguir la similitud entre aquellos a quienes atacaban y ellos mismos: su tez era similar, sus ojos eran similares, sus cabelleras eran similares; hasta sus nombres eran similares.

Era un jueves. Por la mañana, en oficinas, comercios, casas y calles, abundaban las felicitaciones en broma sobre mulas y panzones. Pero por la tarde, todo fue violencia. Era 1971, y un joven corría aterrorizado, sujetando su cabeza ensangrentada con las manos.

Menos de tres años después de la matanza del 2 de octubre de 1968 —ordenada por el presidente constitucional de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, Gustavo Díaz Ordaz—, su sucesor, Luis Echeverría Álvarez, también presidente constitucional por el mismo partido político y elegido en votación popular, ordenó otro plan mortal contra la comunidad estudiantil de México. Aquel día quedaría grabado en la memoria de los testigos como el Halconazo del Jueves de Corpus Christi: 10 de junio de 1971.

La emigración de mexicanos a Estados Unidos, iniciada en el siglo XIX tras la firma del Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) —que estableció la división fronteriza entre ambos países—, eventualmente alcanzó a aquel joven. Como muchos otros, arriesgó su vida en una travesía que prometía, al final, una vida más próspera y segura. Apoyado por la mano empática y generosa de paisanos, llegó a un lugar donde trabajaría la misma tierra que alguna vez perteneció a México, pero en oficios muy distintos a los generados por las industrias minera y ferrocarrilera de principios de la década de 1900.

Así comenzó una vida de trabajo, adaptación y esfuerzo constante, que trajo consigo asedio, precauciones extremas y temores silenciosos, a cambio de un progreso y comodidades hasta entonces desconocidos. Esas migajas de dignidad permitían tolerar la intolerancia circundante, hasta que aquel joven herido por un grupo paramilitar en su país se convirtió en jefe de una familia que ahora esperaba, con ansiedad, a su primer nieto.

Un día, el racismo, la división y el odio parecieron materializarse. Una voz desde el gobierno —que aparentemente se había desvanecido años atrás— regresó, más agresiva y desafiante. Los hombres y mujeres que celebraban esa voz repitieron sus amenazas, y la mano amiga del latino se cerró en un puño decidido a defenderse.

El viento volvió a arrastrar mantas blancas por las calles. Sus mensajes, ahora en otro idioma, eran promesas de paz pisoteadas. Pero esta vez, sus portadores no huyeron: devolvieron el golpe. Y se aplicó la ley. No la ley de la intolerancia, no la ley malintencionada, no la ley divisoria, sino la ley inquebrantable: la violencia solo genera violencia.

El ahora anciano volvió a sentirse como aquel joven que huyó entre gritos, golpes y fuego, con la sangre resbalando por sus manos, cincuenta y cuatro años atrás. Pero esta vez no podía huir. Tampoco pelear. Su deber era proteger. Su instinto, salvar. Buscó refugio para su hija, evitando que su sangre —y la que crecía en su vientre— se derramara.

Nada había cambiado. Los gritos aturdían igual, el humo asfixiaba igual, el fuego quemaba igual, las balas mataban igual, la sangre olía igual y la bandera ondeaba igual. Las voces eran distintas, pero decían lo mismo. Las promesas y amenazas idénticas, tanto de un lado como del otro, tanto de hombres como de mujeres. Los colores eran más vivos, los emblemas diferentes, pero al final, todo era lo mismo.

Al día siguiente, un hombre que llevaba más de una década defendiendo los derechos humanos de los inmigrantes latinoamericanos en Estados Unidos hablaba con un periodista en México. Criticaba abiertamente las nuevas políticas migratorias y la crueldad con que su brazo armado las aplicaba contra civiles. Para ejemplificar la incongruencia, relató cómo había ayudado a una mujer nacida en EE.UU., hija de inmigrantes mexicanos, que fue detenida, encadenada y acusada injustamente pese a su avanzado embarazo. Afortunadamente, la violencia vivida el día anterior en California no afectó al bebé. Sin embargo, en un acto de amor, su padre murió protegiéndola.

English translation

“And the smell of blood soaked the air, and the smell of blood stained the air.” — Fragment from a Nahuatl poem

The wind dragged a long white banner down the street. Its message, now irrelevant, was illegible, and its bearers — courageous just moments earlier — fled in panic. There were screams, explosions, smoke, fire, blows. There was blood. You could smell it, feel it, see it. It was hatred, madness, war. Intolerance and arrogance loomed like black storm clouds over the buildings, darkening a calm, warm day.

The armed men seemed frenzied, furious, drunk on power and impunity. Their trained minds could not process the cries of pain, the pleas, the sobs. Nor could they recognize the resemblance between those they attacked and themselves: their skin was the same, their eyes the same, their hair the same — even their names were the same.

It was a Thursday. That morning, jokes about mules and potbellies filled offices, shops, and streets. By afternoon, there was only violence. The year was 1971, and a young man ran terrified, clutching his bloodied head in his hands.

Less than three years after the October 2, 1968 massacre — ordered by Mexico’s constitutional president, Gustavo Díaz Ordaz — his successor, Luis Echeverría Álvarez (also a constitutionally elected president from the same party), orchestrated another deadly assault on Mexico’s student community. Witnesses would forever remember it as the Corpus Christi Massacre: June 10, 1971.

The migration of Mexicans to the U.S, which began in the 19th century after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) redrew the border between the two nations, eventually swept up that young man. Like so many others, he risked his life on a journey promising prosperity and safety. With help from the empathetic, generous hands of fellow countrymen, he arrived to work land that had once been Mexico’s — though in roles far removed from the mining and railroad industries of the early 1900s.

Thus began a life of relentless work, adaptation, and struggle, marked by harassment, extreme caution, and silent fears, traded for unfamiliar comforts and progress. These shreds of dignity made the surrounding intolerance bearable until the young man, wounded by paramilitaries in his homeland, became the patriarch of a family now awaiting its first grandchild.

Then one day, racism, division, and hatred seemed to materialize anew. A voice from the government — one many thought had faded years earlier — returned, louder and more aggressive. Those who cheered it repeated its threats, and the Latino’s open hand clenched into a fist ready to fight back.

The wind carried white banners through the streets again. Their messages, now in another language, were trampled promises of peace. But this time, their bearers did not retreat: they struck back. And the law was enforced. Not the law of intolerance, not the law of malice, not the law of division — but the unbreakable law: violence begets violence.

The now-old man felt like that young fugitive again, fleeing through screams, blows, and fire, blood dripping from his hands fifty-four years later. But this time, he couldn’t run. Nor could he fight. His duty was to protect. His instinct, to save. He sought refuge for his daughter, desperate to keep her blood — and the life growing inside her — from spilling out.

Nothing had changed. The screams deafened the same, the smoke choked the same, the fire burned the same, the bullets killed the same, the blood smelled the same, the flag waved the same. The voices were different, but the words identical. The promises and threats mirrored each other, from one side to the other, from men and women alike. The colors were brighter, the emblems unfamiliar, but in the end, it was all the same.

The next day, a man who had spent over a decade defending Latino immigrants’ rights in the U.S. spoke to a journalist in Mexico. He openly condemned new immigration policies and the brutality with which they were enforced. To highlight the hypocrisy, he recounted helping a U.S.-born woman, daughter of Mexican immigrants, who’d been detained, shackled, and falsely accused despite her advanced pregnancy. Miraculously, the violence in California the day before had not harmed her child. Yet in an act of love, her father had died shielding her.

Julio Balderas es el autor de La Herencia de los Señores de San Roque y Sangre de Chacales. Él es un escritor siempre en busca de la siguiente historia.

Julio Balderas is the author of Inheritance of the Lords of San Roque and Blood of Jackals. He is a writer always looking for the next story.

Este artículo es presentado por El Vuelo Informativo, una asociación entre Alcon Media, LLC y Tumbleweird, SPC.

This article is brought to you by El Vuelo Informativo, a partnership between Alcon Media, LLC and Tumbleweird, SPC.