Free at Last

Here I am, little ol’ me, Joseph Jean Thompson the third. Only 13 years old, standing here with my mother and older brother, Abigail Thompson and Charleston Thompson. Watching my grandfather hang from our master's maple tree. With his organs ripped out. With his blood creating a trail — a river that runs to a lake of blood on the grass. My nostrils are filled with the scent of rotten eggs, mildew, and spoiled milk, causing my stomach to turn. I squeeze my eyes tightly and whimper.

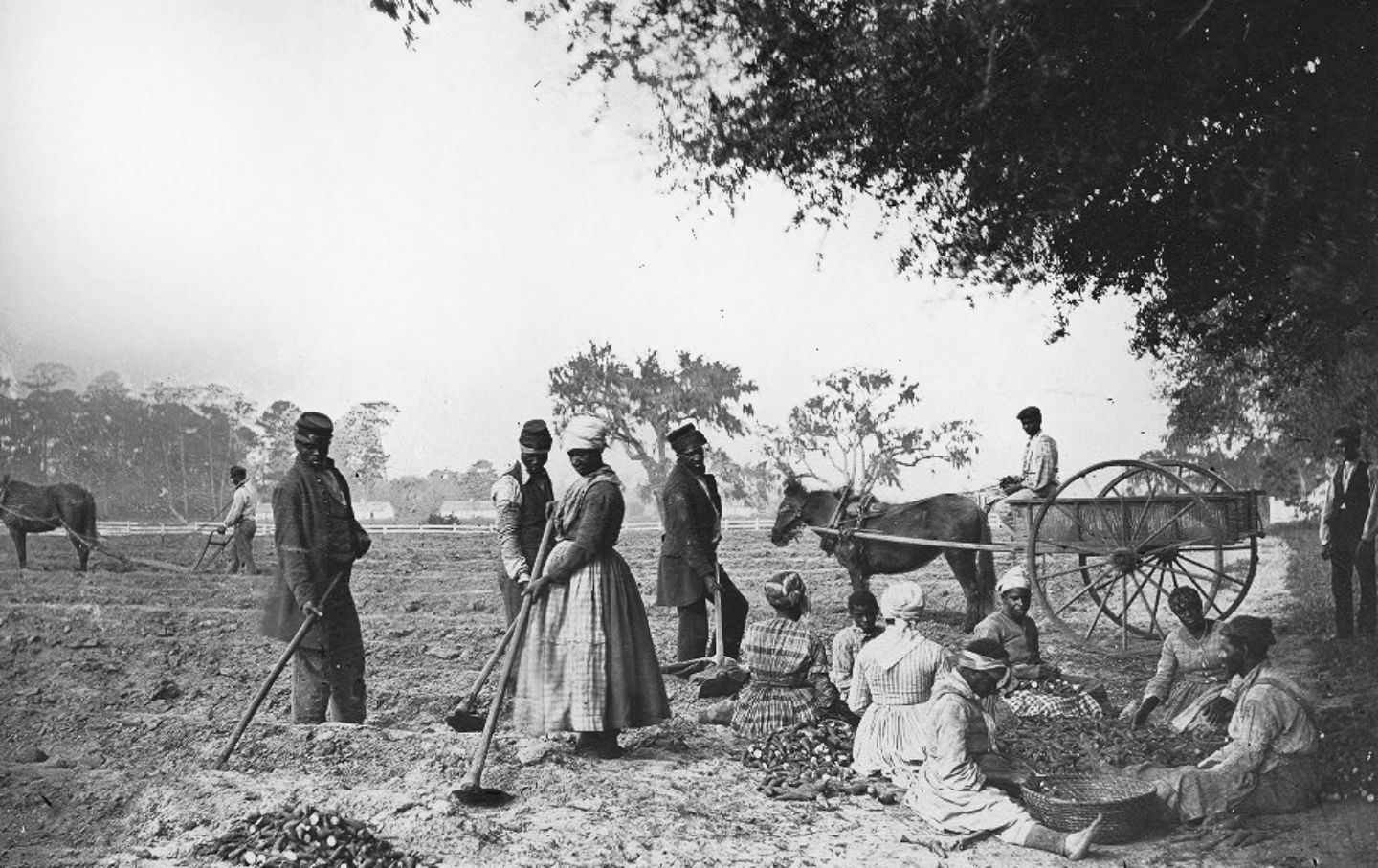

Out of the corner of my eye, I see my big cousin George Patterson getting whipped by the master's younger son, giving him dents as long as his forearm. I can see the meat and bones inside his back, as though he is being cut open with a blade for surgical treatment. I hear the hollering of my neighbor's child as her mother stitches, patches, peels, and oils the wounds on her hands from being forced to pick 100 pounds of cotton.

I see slaves exiting slave ships in chains and shackles. Their wrists are bloody, swollen, and bruised. The skin on their ankles burns as it is scraped off by the manacles. The chains around their necks create rashes and scabs. They are so thin, they look like skeletons, their teeth as yellow as bananas, their lips as dry as the sun. They are covered with lash marks on their bodies from head to toe.

They are forced to line up in a single file line as my master sells them one-by-one, from youngest to oldest. The slaves beg for nourishment and hydration, with their tongues as dry as a desert and their stomachs as empty as a bird's nest in December.

They are covered with lash marks on their bodies from head to toe.

Soon after, I spot a big bag that my master’s men carry out. As I sneak a quick glance of what it holds, I see chunks of Black body parts — pieces of those that had died, ranging from ages 7 to 65. They are being thrown into the fire as if they are just old rags, rotten vegetables, or expired fruits.

As I turn around, I see runaway slaves sprinting through the cotton fields, carrying only a few cans of potatoes and beans, and tiny crumbs of bread they found inside my master's garbage. They have no shoes, and for clothing, only have half-ripped pants, and shirts with holes as wide as the moon itself. I watch as their breath becomes heavy, I see their adrenaline rise, and their anxiety erupt. The cotton pokes and scratches the sides of their outer flesh, leaving blood stains as red as tomatoes upon the edges of the cotton. And then I also hear the horses’ hooves, the dogs barking, the whips cracking, and the loud guns firing out bullets. I watch as the master’s brothers shoot them dead, when all they wanted was to be free.

My mind begins to wonder: Why must we live like this? Why must we live with torture and misery? Why won’t they let us read? Why did they strip us from our African homeland? Why do they punish us for speaking our own language and force us to learn theirs? Why do white pastors preach about God wanting us to obey our ‘masters’? How much more do we have to bear? The hurt and struggle is becoming too much to sustain.

Suddenly, the sun begins to shine as bright as it ever has. The clouds part like the gates of heaven and the brilliant light shines through. The rain vanishes, and the fog runs away as though it’s being sucked up with a vacuum. I feel like angels are about to come down from the sky with drums, triumphantly singing a peaceful melody.

“Free at last! Free at last! Free at last! Free at last!”

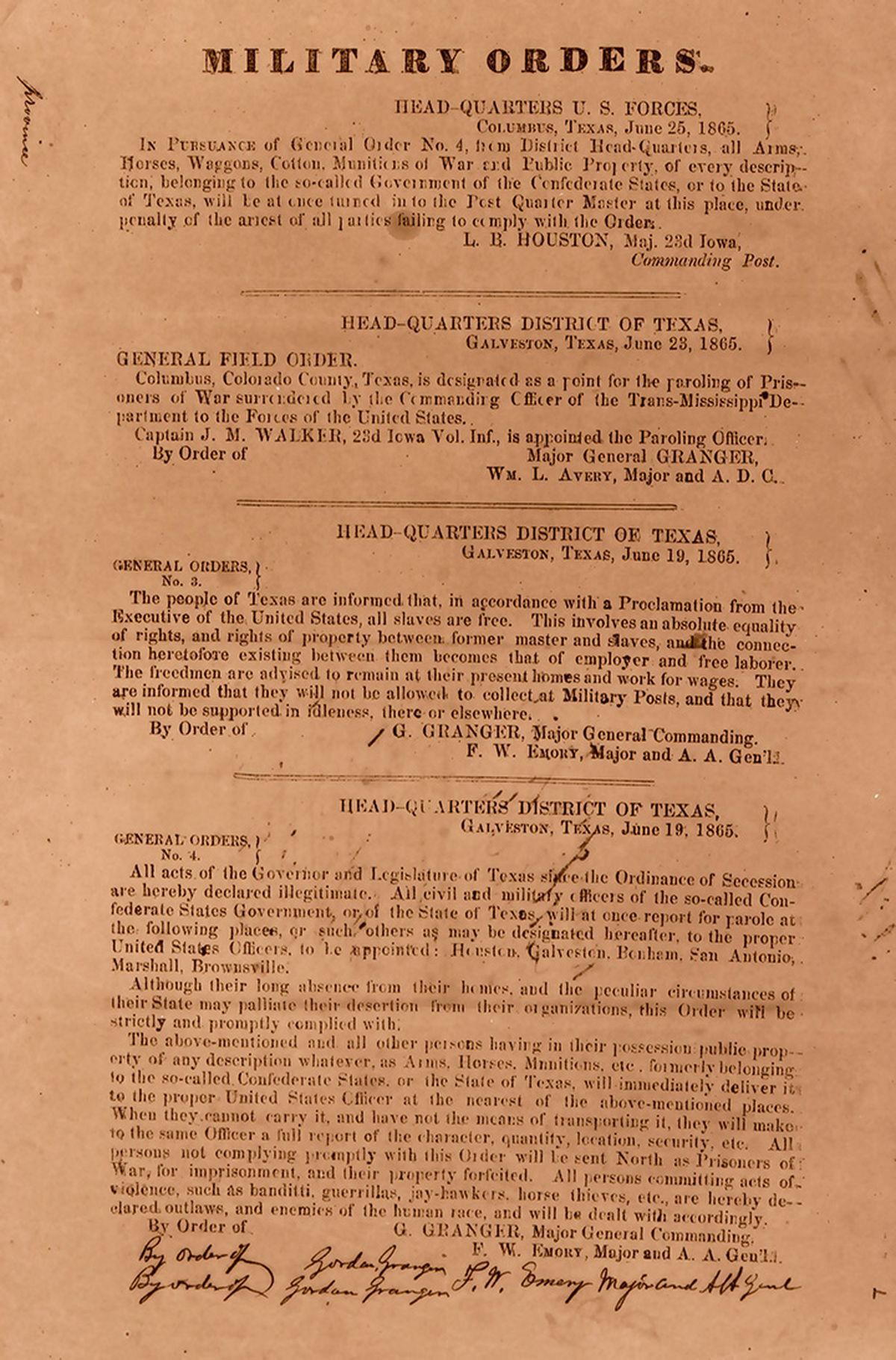

I hear loud and heavy footsteps 2,000 strong — tall union troops arriving at my master’s front lawn in Galveston Bay, Texas. I stare in disbelief as they announce that more than 250,000 enslaved Black people in the state are free by executive decree. Today, June 19th, 1865 at 4:00pm sharp. All I can do is fall to my knees, praising and glorifying my savior Jesus Christ for this miracle — for answering my prayers.

After a few moments, I jump to my feet, and I begin to joyfully repeat:

“Free at last! Free at last! Free at last! Free at last!”

Anyla is a student at Walla Walla High School. She aspires to become a poet, short story writer, and essayist speaking about racism against Black people, current world problems, and hot topics. When she writes, she does it with purpose and passion. Anyla feels destined to touch others with her words, and wants to be known as someone who takes a stand and impacts lives with her writing.