Beginning in July, I am featuring a monthly interview with one of our resident environmental advocates in a series we’re calling Digging Deeper. I aim to reveal a bit about what leads these folks toward a career in nature.

Steve Ghan, our local face and voice of Citizens Climate Lobby, is recognizable here as a regular contributor to Tumbleweird. This interview is condensed from a 40-minute conversation.

— Section Editor

Steve Ghan: I grew up in Bellevue, Washington. My parents liked the outdoors, and so they took my twin brother and me backpacking. When we were eight, about 1965, we went out to the Olympic coast and backpacked three miles to Cape Alaba and set up camp next to the beach. Little did we know that this was the weekend of the Columbus Day storm.

We spent two nights up there, and the next day we went for a walk along the beach out to the actual Cape, Cannonball Island, surrounded by round rocks. My brother and I were climbing around, playing on the driftwood, having a great time, not noticing a storm approaching. What started with hailstones and wind quickly got nasty. We were a half mile from our camp.

We noticed a cabin above the beach. Once inside, we found it was cozy, and decided to spend the night. Drawing the short straw, I got to return to camp with Dad to retrieve our gear. Eight years old, carrying two peoples’ worth of gear on my back, I fell behind. Suddenly a huge gust of wind blew me on my back, turtled up, wind howling, waves crashing. I yelled out, “Dad! Dad!” but he couldn't hear me.

After what felt like forever, he stopped, turned around, and saw me flailing. Standing me back up, he stayed closer as we made our way to the cabin. A warming fire and hot meal comforted all of us. That storm roared all night. What an introduction to backpacking!

Jenny Rieke: So eight years old, turtled up by a mighty wind… How did you not decide that nature sucks?

SG: There was something about it, just the wildness of it.

Once we were introduced to Boy Scouts and went on 50 milers, we had wonderful times up there in the mountains. When we were sixteen, an article in the National Geographic inspired us. Eric Ryback was the first person to claim to have hiked the entire Pacific Crest Trail. We thought, wouldn't that be cool? But we were sixteen and thought maybe that's a bit much for us. So, we settled on hiking the Washington portion of the PCT.

We planned it all out, got all the maps, and geared up for it, including a three-person tent. Having backpacked with the scouts, we knew to have a third person along in case of trouble. We invited different people to come on different sections of it.

It was the hardest thing I’d ever done. We started at the Columbia River, headed for White Pass 150 miles away, and planned on 10 days to do it. [We had] fifty-five pound packs, and I weighed 123 pounds. About halfway through, my waist belt broke. It was hard. I had terrible blisters from those little leather boots, but we made it up to Canada. This was really a coming of age experience for me. I learned that I really did enjoy backpacking.

JR: Describe your learning path to becoming a climate scientist.

SG: Science was my interest in high school. My college major in atmospheric science focused me on climate change as an issue. A new climate program became the basis for my career. Once I got my PhD, I started learning about global climate models and how they could be used to simulate global warming. Lawrence Livermore National Lab, followed by Pacific Northwest National Lab, allowed me to work on a team that developed global climate models running supercomputers to simulate global warming.

I was very much aware of how much local climate depends on surface elevation, and so I cooked up a scheme of representing the complexity of mountainous terrain in a global climate model. I was really interested in mountainous local climate and the importance of mountain snowpack to farmers. A 50% loss in summertime irrigation water, without additional artificial reservoirs that negatively impact fish and wilderness, posed a pretty scary situation.

JR: Such deep knowledge and understanding of the impending crisis. What made you become a vocal advocate about climate change?

SG: I started speaking to the public, because I noticed pervasive confusion about the science. I soon found more acceptance of the science as they also heard about solutions. Seeking solutions, I learned about a sensible policy of putting a price on the carbon content of fossil fuel, then giving everyone an equal share of the revenue, no matter how much carbon they use. No tracking, [just] a carbon dividend deposit in your bank account every month. The less carbon used, the more you get back.

I learned about this from Citizens Climate Lobby, and have been an active member ever since. We advocate for national policy by building relationships with members of Congress. The inflation Reduction Act subsidized electric vehicles, wind turbine solar panels, batteries, and all sorts of things. Our representative, Dan Newhouse, signed on to a letter to the Chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, urging continuation of subsidies for energy tax credits.

JR: Have you ever tried to stop a bad habit in yourself? Young people have been taught by society, by their family, by whomever, some pretty bad habits. I mean, we are easily in a groove with wastefulness and consumerism and the fossil fuel way of life. I'm wondering how you might tell young people how they can be empowered to choose different habits.

SG: First is to model it. Whenever I speak at a high school, no matter where it is, I always bike there. And I tell them that's how I got there. And I ask them, “How many of you have bikes? How many of you ride your bike? When's the last time you rode a bike?” I also ask them, “How often do you talk about climate change?” I find that they don't talk about it.

In the absence of economic incentives, I aim to show them that they can make a difference in terms of what they eat. We talk about methane emissions from the meat industry, and meat alternatives and how tasty those are. We discuss electric vehicles (a pretty easy sell). My message is that you don't need to sacrifice much. You just need to make choices that consider climate impacts, if you don't have incentives. Choose to Zoom instead of air travel.

JR: I’m not sure there’s a bike rack at Chiawana High if a student wanted to ride. Students drive, walk, or get dropped off. And of course, there are some buses. The traffic on Argent when school starts and lets out is stunning. In each car there's one kid; few, if any, carpools.

SG: I'm a lifelong bicycle commuter, and I love that, and there are safe routes to bike. Yeah, we could certainly use more riders.

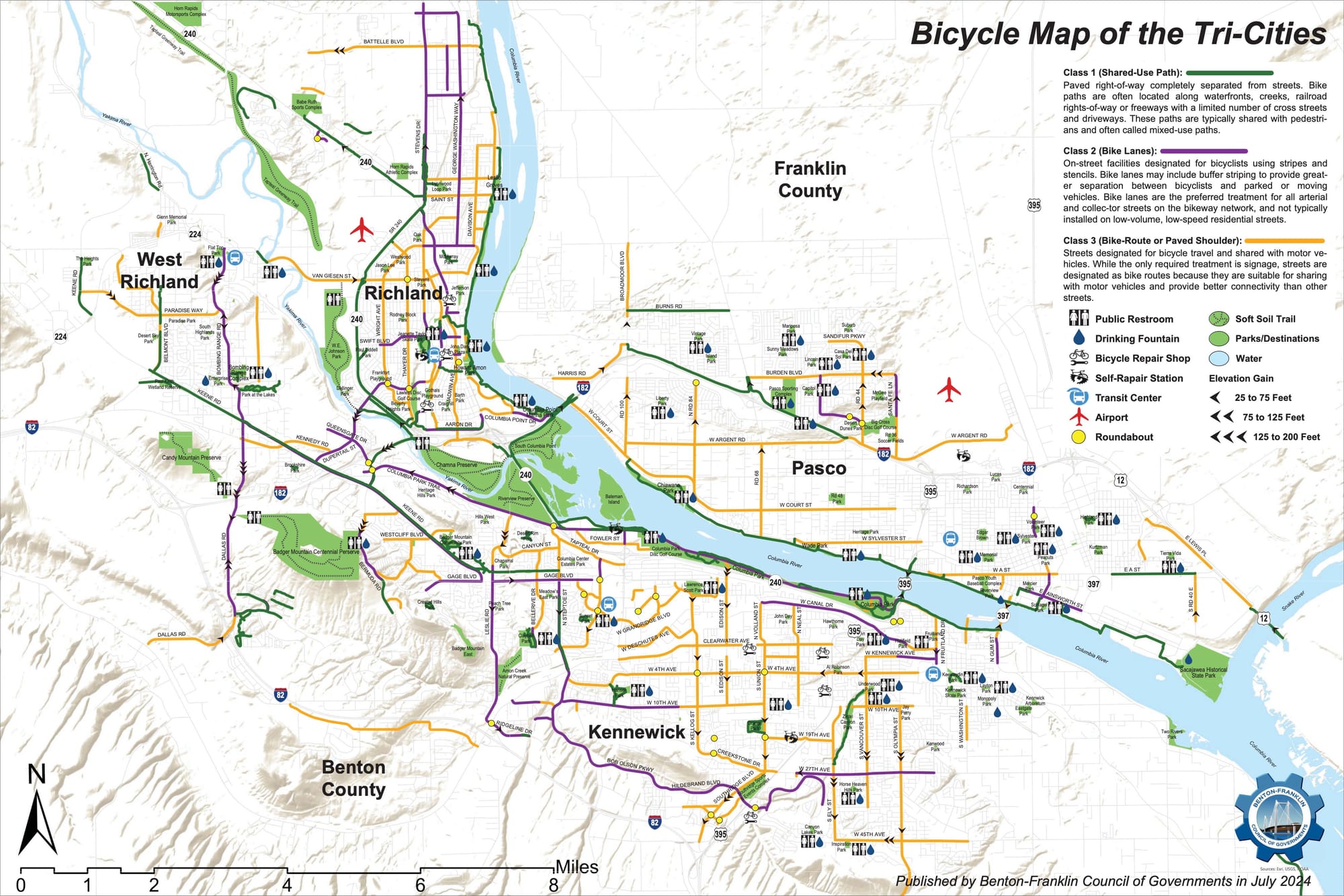

JR: Exemplary synchronicity in the April issue of Tumbleweird: your article AND the Tri-Cities regional bike map! I thought with the map we might inspire explorers to get out there and learn the trails. Perhaps Bike Tr!-Cities could routinely tour the highschool circuit to encourage this good choice.

SG: I know the folks at Wheelhouse are very good with outreach. Perhaps they could lead an effort. Yeah, throughout the Tri Cities, we need more kids on bikes. And routes need to be safe for all bike riders.

JR: Sharing our thoroughfares is going to be the focus of Boots in the Basin soon. We have water trails, land trails, hiking trails — all kinds of trails. Those who feel entitled to own the trail do not necessarily yield to others.

Alright, change of subject: Describe your perfect natural refuge.

SG: Up at White Pass, breaking trail through 26 inches of fresh snow. So quiet alone out there, so peaceful.

JR: Growing up in Montana, I learned to revere the hush of a snowy landscape. Even when Pasco gets a mere inch of white, I go outside and simply take it in, because it is silence. It mutes everything. I grew up with snow, and I miss it, because it was day after day after day.

Is there someone who's influenced you the most? Do you have a hero in this realm?

SG: I certainly had mentors in college for academics, but someone who's really influenced my advocacy is Katherine Hayhoe. She's an atmospheric scientist, a climate scientist, and she's a wonderful communicator. She knows how to ask people questions and cut through the crap. So many people have all these pseudo scientific arguments about climate change, and that's all really motivated by fear of climate solutions. There's a lot of messaging out there about how we can't solve climate change unless we get rid of capitalism. Katherine doesn't make it into a political deal. She says everyone's an expert on climate because everyone's had their experience of how things are.

JR: Do you have a promise you make to yourself for your daily nature connection?

SG: Get outside. Go for a walk. We climb Badger and Candy Mountains three times a week. And outside of that, we'll walk along the river.

JR: What is your personal mission?

SG: My personal mission is to empower as many people as I can to be effective advocates for actual climate change, because I can't do it alone.

JR: Well, I kind of look to you as our local guy who has a clue. And you have much more than a clue about how to help locals find a meaningful path forward. It’s going to be the young people, because the older people our age, I mean, you're either in the conversation or you're just ignoring it completely.

How do we give young people hope? Think of all the STEM graduates we have. How can we support them, especially now as the EPA is being gutted?

SG: As I said, I was very aware of the impact of global warming on mountain snowpack, a really big deal here in the Western U.S. And I was somewhat aware of global economic impacts, but I never really felt climate grief until I attended a workshop during my hike on the Pacific Crest Trail [in 2021]. The young people attending the workshop were very much in touch with their feelings, and they were depressed. Talking with them, I learned that they were not very hopeful about climate change. They’d learned all about the impacts of climate change in college, but didn't learn about solutions.

I returned to the tra

il and I thought about these young people. As I walked up the trail, it suddenly hit me what they were feeling. They’re the ones who are really going to experience how bad it gets. And I just started crying, I really felt that climate grief.

JR: I want to offer Tumbleweird readers some sustenance, some hope.

SG: Yeah, when I talk with the public, I talk less about the science, almost always discussing solutions — both the technologies and the policies that drive the implementation of those policies. I also teach high school students by balancing science with solutions. We play a game based on a free climate simulator. Run off a browser, it takes 19 different climate change solutions, and estimates their impacts on energy use from all the different sources, and carbon emissions. The carbon cycle model predicts carbon concentration for the rest of the century, and then how that affects climate. We discuss each solution and its individual effectiveness. I then group the students into teams and challenge them.

If we don't do anything more than we're doing now, the climate will warm 3.3º C. The goal is to limit global warming to 2º C. Resources are limited; you must choose three of the 19 solutions. With 15 minutes to meet and talk it over, they come to consensus on three solutions. A team representative announces their selection and justifies it. Each team runs the simulator with their choices to see how effectively they work. They really get into that. I think such an activity builds a sense of hope.

JR: Can you recommend any good reads for people wanting to wrap their heads around what it means to face our changing climate?

SG: Donut Economics by Kate Raworth is about the notion of planetary boundaries in all sorts of areas like energy, climate, water, etc. Raworth acknowledges that we can't exceed that limit, but everyone needs a certain amount of resources to live. Between the minimum we need to live and the maximum that's allowed for a sustainable planet is a ‘donut of existence’ in these different areas of resources. Ideas about how to motivate people to conserve resources include repairability as an important concept: buying used, repairable things instead of replacing broken things with new. There is a ‘right to repair’ movement out there, where the manufacturers have to make their products repairable and provide instructions. That's a good thing.

JR: It’s supporting the worst of society to just constantly throw it away and get new; yet, that's how generations of kids have grown up. In addition to losing a connection with nature, young people are not connected with the empowerment of ‘fix-it’: to find out how it works and try to repair it. How does that seed take hold in a young person so they realize they can choose?

Your climate simulation workshop is a whole empowerment process, and that has to happen over and over so they believe it's real and transferable. Otherwise, it's just a fun activity. It’s clear that we must educate continuously any way we can.

SG: Sometimes on the trail … one of the first questions a fellow hiker asks is, “It's too late, isn't it?” I respond that it's too late for what's already happened, yeah; and it's too late for things that are going to happen because of the carbon we've already put in.

But conditions can always worsen, so we can prevent it from getting worse.

Let's do that.

Climate scientist Steve Ghan leads the Tri-Cities Chapter of Citizens Climate Lobby.