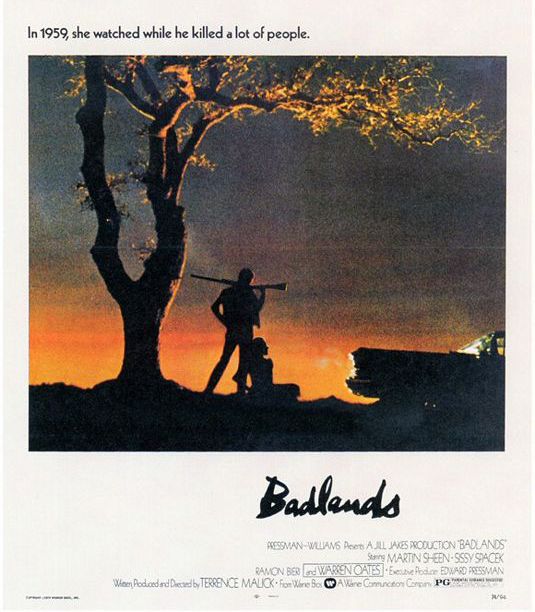

Badlands and many other films are available to check out from Mid-Columbia Libraries.

Director Terrence Malick titled his 1973 debut feature Badlands, but the term is a misnomer. The quiet beauty of the natural world ends up serving as the only grace in a human universe where goodness barely exists. In particular, dogs represent an innocence and purity that gets squelched as atonement for the sins people commit. When our young antiheroes, Holly and Kit, attempt to keep secret their budding, forbidden romance, the girl’s overbearing father determines as satisfactory punishment the gunning down of her pet. A harmless creature meets its unjust end in a field of green, the tall grass enveloping the unburied carcass like a cocoon.

Cinema’s limitations, fortunately, spare audiences the stench that emanates from canine, bovine, and human corpses cooking under Badlands’ constant Midwestern sun. Nonetheless, the invisible threats of violence and death hover palpably. The main characters act as both merciless agents and imagined victims of these forces. Criminals sensing their imminent fall appear most memorably in 1940s film noir; and trigger-happy Kit, speaking into a dictaphone before the law makes its final move, resembles the doomed Walter Neff of Double Indemnity. But while Neff records his confession as a final, frenzied shot at repentance, the self-justified madman of Badlands finds another chance to shoot his mouth off with such hollow moralizing as, “Try to consider the viewpoints of others.”

Others share Kit’s habit of trying to capture and preserve an ever-receding present. Holly lost her mother when only an infant, and as she tells us through voiceover in the film’s opening scene, for years her father kept sealed in the fridge an uneaten cake from the wedding with his long-gone wife. In contemplating death, Malick also ponders the hidden life contained within inanimate objects, those everyday items we endow with memories as our feeble but still necessary safeguard against time.

This practice carries with it a danger, however: rely too heavily on things as an escape into the past, and the fleeting now diminishes in value and vitality. Worse still, one starts perceiving all the world — including the people that occupy it — as dull, soulless surface. Only a view this amoral makes Kit’s killing spree explainable (at least to him). Malick loosely based his fictional creation on real-life sociopath and murderer Charles Starkweather, who ironically sought inspiration from the movies (James Dean’s tortured onscreen persona) to craft his look in the late 1950s. In an interview decades after Badlands’ release, actor Martin Sheen reflected on both the temperament of Kit and American society at large: “We were more into image than reality.”

Malick himself rode that first generational wave of filmmaking that, thanks to a rise in accessibility to media from across the globe, honed its craft by studiously watching and re-watching the masters of celluloid. A few years before Badlands began production, famous French artist François Truffaut made The Wild Child (a title which could have aptly described Malick’s work as well). The stateside director and his editor Billy Weber noted the unique use of voiceover in Child, and strived to achieve a similar effect in their film. Such stories fill the highway that stretches across Seventies American cinema — to a degree, the ingenuity of Malick and others had less to do with a bold departure from established technique and more with imaginative assimilation and reinterpretation of the media they consumed.

Kit lives out this attitude through the various artifacts that happen to enter his path. He inspects each with a restless curiosity and retains what suits his purposes in the moment; that which doesn’t gets discarded (sometimes fatally). His ruthlessly practical eye nonetheless has its quirks, falling upon the occasional person (Holly) or thing (a stone) ignored by everyone else, and mining for undiscovered potential. Kit’s real-world counterpart, Martin Sheen, noted a similar experience during the making of Badlands. Already over 30 years of age, and with little else on his resumé than small parts on television shows, Sheen finally found in Malick a leader with the vision to recognize what others had overlooked: his considerable acting talents. With support from the director’s chair, Sheen gives us a spellbinding, lived-in portrayal of one of cinema’s most charismatic killers.

What characters choose to see or not see matters a great deal in Badlands, but so does their power to hear. Growing neglect from her self-absorbed, talkative boyfriend forces quiet Holly to withdraw deeper, even to the point of — as she poignantly describes — using her tongue to write unsaid thoughts on the roof of her mouth. Though unseen and unheard ourselves, we in the audience serve as the girl’s most sympathetic listeners as she narrates her strange tale. Kit, meanwhile, lost and aloof in his own way, goes off to take in the endless plains. Slack-jawed he stands, “the world’s mute radiance” unfurling before him. He grows surprisingly silent, perhaps wishing for nature to confer healing words of absolution. Time could stretch as far as the land under his feet, but the answer he seeks will never arrive.

A precious commodity for these lovers on the lam, time also leads all life into death. Such a transition may come roughly and without warning, the film points out. The very first shot takes us into Holly’s bedroom, where she contentedly strokes her panting dog, while across town, Kit peers at another canine lying dead in an alley during his shift as a garbage collector. Other images in this early morning sequence have a sort of sad stillness — suburban streets with no movement, no activity. As a counterpoint to a warped young man’s impulse to rub out others for convenience, these visuals from a masterful debut film remind us to value life’s fleeting fragility.