Building a world where no one has to ‘earn’ compassion and care

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared on whtwnd.com in June 2025 and is reprinted here with permission. The original article has been edited for style and length.

A few weeks ago, an old American acquaintance was visiting Portugal with his companion, whom I’d never met. They traveled from Lisbon to Porto for a day trip to see me and the city I now call home; but unfortunately, their visit happened at the same time as one of my atypical migraine attacks. Not wanting them to have taken the train up to Porto for nothing, and genuinely wanting to catch up with someone I hadn’t seen in years and get news from my hometown, I tried to push through my misery — a big mistake.

My wife and I sat at an outdoor table across from our guests near the train station. Having barely escaped suffering a full-blown panic attack on the train platform while waiting to greet them, I was desperately trying not to be sick from the smell of food, the brightness of the sun, and the sounds of passing traffic. Sunglasses on and earplugs in to try to keep anxiety and nausea at bay, my old friend’s partner attempted to strike up a sympathetic conversation to inquire about my obvious misery. I explained that I’d started having debilitating sensory sensitivity and migraines after a car accident triggered a stroke three years ago. Casually, she asked who was at fault in the accident, to which I responded that it was the other person’s fault.

Not long after this exchange, my wife finally convinced me that I should catch a taxi ride home. She would give the couple (complete strangers to her) a tour of Porto without me. Probably green in the face by this time, I was in no position to argue, so I regretfully said goodbye to the other Americans and slumped into the backseat of the car that arrived minutes later.

Who was at fault? This woman’s casual inquiry bothered me for some time after that miserable day, though I couldn’t quite put my finger on why, yet. I doubt she was consciously aware of it, but I think the point of the question was to help her determine whether or not I was truly deserving of sympathy. If I had told her I caused the accident, would she have subconsciously held me responsible for my own suffering? Why should being at fault for an accident make someone less worthy of sympathy?

I’m writing this essay in an attempt to articulate how deeply we’ve internalized the belief that suffering must be earned or deserved. Her need to determine fault wasn’t personal cruelty — it was the automatic response of a mind shaped by centuries of Puritan-influenced thinking that divides the world into the deserving and undeserving. But the discomfort I felt about that question grew into a recognition that our society’s approach to suffering and care is fundamentally broken. We ration empathy based on perceived fault, celebrate individual achievement while ignoring systemic barriers, and treat interdependence as weakness rather than human reality. I want to illuminate different facets of this problem — from historical mythology, to disability narratives, to models of mutual care — because I think understanding these connections is the first step toward unraveling them and building a more humane society.

Who is deserving of sympathy: The historical roots of conditional compassion

The Puritans came up in conversation with a Portuguese woman a few weeks ago. Educated in the UK, she had asked me if it was true that American children learn that the Puritans were a persecuted religious minority that came to the New World seeking religious freedom. When I told her that yes, that was what I’d been taught in school in the U.S, she was aghast. In her school, they were taught the Puritans were religious extremists who fled the repercussions of their subversive activities.

To be fair, there are true elements to both accounts. Actual historians are welcome to correct me, but my casual reading of history indicates that the Puritans were victims of religious persecution because they were challenging the legitimacy of a religious monarch’s claim to absolute power in a politically- and religiously-charged era of change.

Historical narratives are often shaped to fit the mythologies and ideologies that serve the interests of those in power, and we would do well to never forget that (and to remember that those in power want us to forget). The Puritan values that have both shaped and served the interests of those in power from before the inception of the United States to the modern day have been deeply ingrained in the American psyche, influencing our attitudes towards personal responsibility, the value of work, and the meaning of suffering.

As it happens, one of my favorite YouTubers, Zoe Bee, just put out a fantastic long-form video essay on The Many Myths of Meritocracy.1 To understand more about what meritocracy is, where these beliefs come from, and what they are doing to us, please do watch it.

But to vastly condense the concept for the purposes of this essay, meritocratic beliefs influence whether we receive sympathy, support, or even basic respect based on others’ perceptions of whether we are at fault for our suffering or not. The idea that suffering is either deserved or undeserved remains a pervasive stain on our collective consciousness.

Now, I’m not the first (and certainly not the last) disabled person to notice how this mindset affects how we are treated by the able bodied. Disabled people whose conditions are seen as the result of external factors are more likely to be viewed as deserving of help and sympathy, while those whose disabilities are perceived as linked to lifestyle choices or personal failure are more often stigmatized and blamed for their conditions.

This way of thinking is not only harmful, it’s also fundamentally flawed. It ignores the complex interplay of factors that contribute to disability and suffering. It overlooks the fact that anyone can find themselves in circumstances beyond their control, and that empathy and support should not be conditional, dependent on perceived innocence or fault. This mindset perpetuates a culture of judgment and division, encouraging us to view others through a lens of moral superiority, rather than with compassion, understanding, and mutual responsibility towards each other.

Supercrips, inspiration porn, and the commodification of suffering

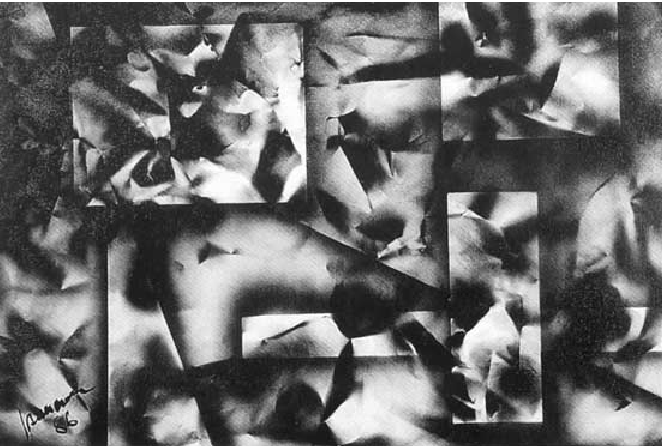

On a recent outing, I was talking with another American friend who lives here in Portugal. As we walked from the art exhibit we’d just visited to a nearby restaurant, he asked me about the cognitive and visual deficiencies I acquired as a result of my head injury. He then told me the account of an anonymous artist he’d read about who was in a car accident and suffered a brain injury that destroyed his ability to perceive color. The way he told it, the story was an inspirational one — a tale of an injured painter, at first deeply depressed by his loss of ability to see in color, who adapted and overcame his limitations and eventually returned to his painting in black and white — and how those paintings made him an even more ‘interesting’ artist… a man worth celebrating.

The implication was that I needn’t feel depressed about the loss and suffering I’ve experienced as a result of my stroke. There is hope! Chin up, you just need to find out what makes you special, like that artist did!

At the heart of this projection of inspiration overlaying tragedy lies the able-bodied person’s fear of disability that manifests in a meritocratic, individualist society that discards disabled bodies. It is a means of self-soothing at the expense of those seen as no longer worthy of being soothed.

I’m sure this friend of mine thought he was being helpful. Most likely, he has no idea that his recounting of this artist’s story left me feeling irritable and hurt, or that it makes me want to keep him — and his offensive ableism — at arm’s length. I looked into this artist (you can read about him in The Case of the Colorblind Painter, which is as fascinating as it is horrifying) whose brain injury affected his color perception.2 Where my friend found a comforting story of a newly colorblind artist overcoming adversity — an inspirational tale of a supercrip — I read it as an uncomfortably familiar tragedy about a man whose injury led to intense depression, disgust, dependence, and suffering.3 While he made the best of it, eventually taking up the brush again and adapting his style to express the way he saw the world after acquiring a new disability (much as I have done with my writing), to imply his injuries were some sort of blessing in disguise that made him special is just exploiting a disabled person’s pain for the pleasure and comfort of a non-disabled spectator.

The tragic reality behind the inspirational artist

To illustrate my point, I am sharing the following passages excerpted from an interview conducted with the colorblind artist:

[Mr. Jonathan I] found his entire studio, which was hung with brilliantly colored paintings ... now utterly gray and void of color. His canvases, the abstract color paintings he was known for, all were grayish or black and white, unintelligible. Now, to horror there was added despair: even his art was without meaning, and he could no longer imagine how to go on. It was not just that colors were missing, but that what he did see had a distasteful, “dirty” look, the whites glaring, yet discolored and off-white, the blacks cavernous — everything wrong, unnatural, stained, and impure.

Mr. I. could hardly bear the changed appearances of people (“like animated gray statues”) any more than he could bear his own changed appearance in the mirror …. He found foods disgusting in their grayish, dead appearance and had to close his eyes to eat….

He encountered difficulties and distresses of virtually every sort in daily life, from the confusion of red and green traffic lights (which he could now distinguish only by position) to a virtual inability to choose his clothes. (His wife had to pick them out, and this dependency he found hard to bear….)

It was, he once said, like living in a world “molded in lead.”

Music, curiously, was impaired for him too, because he had previously... had an extremely intense synesthesia, so that different tones had immediately been translated into color…. With the loss of his ability to generate colors, he lost this ability as well … [T]his, for him, was music with its essential chromatic counterpart missing, music now radically impoverished.

…. He sometimes tried to evoke color by pressing the globes of his eyes, but the flashes and patterns elicited were equally lacking in color. He had often dreamed in vivid color, especially when he dreamed of landscapes and painting; now his dreams were washed-out and pale, or violent and contrasty, lacking both color and delicate tonal gradations.2

What my friend was doing was indulging in inspiration porn,4 objectifying disability (note: that which is objectified can be more easily commodified), and exercising survivorship bias in the service of maintaining his comforting belief in meritocracy.5 His attention singled out one specific aspect of the artist’s story — that he started to paint again and his post-injury paintings were ‘interesting’ to others — while neglecting all the other information about what this man endured for the rest of his life. My friend discarded the struggle and sense of loss and revulsion experienced and expressed by the man, and focused only on what the spectators got out of his pain — the paintings and the story to accompany them.

These kinds of stories offer relief to observers: Even though disability could strike any of us at any time, it’s going to be okay because you, too, can still find a way to deserve care and dignity through productive work. (Never mind that the ‘work’ is just objectified suffering expressed in the form of art-turned-commodity). Your disability could even be a gift, too!

By elevating this one aspect of the man’s story, my friend negated his suffering, ignoring and dismissing the reality that vastly more disabled people — who will not be ‘interesting’ or inspirational to the able-bodied — will struggle with exclusion and hardship and die in obscurity. We will not be considered worthy of life. No; that would be too terrifying to confront.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. We must reject the comforting but ultimately destructive notions of individualism and meritocracy. We must reject objectification of disability, commodification of suffering, and the grotesque belief that the value of human life is measured by its relation to the means of production. We must affirm again and again that all life has intrinsic value and every living being is deserving of dignity, compassion, and care.

To move forward, we must challenge these deeply ingrained beliefs in ourselves and others and strive for a more compassionate, inclusive, and collaborative society. We need to recognize that suffering is not a moral failing, and that everyone deserves dignity and support, regardless of the circumstances that led to their condition. And we especially need to see how our wellbeing is interconnected with that of others, and that our ability to collaborate and cooperate is our strength.

The power of collective care

That leads me to one more recent conversation that demonstrates our interconnectedness. A dear friend of mine recently escaped from the U.S. to Mexico with her partner, who had been brought to the U.S. as a child and eventually granted reprieve as an undocumented immigrant under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. As many readers will know, protection under DACA is in jeopardy under the current fascist regime, and people like my friend’s partner are in grave danger.

My friend told me about how her partner had always been made by his mother to send a small portion of his earnings home to Mexico, to family members he’d never met. My friend admitted she’d always felt some resentment about this. “Why should he have to send his hard-earned money home to people he’s never even met?” As it turns out, that money was supporting about 30 family members, and now that he and my friend are essentially refugees in Mexico, my friend has changed her tune. Her partner has been given a hero’s welcome. He’s seen as the distant American relative who has enabled their survival all these years. And now my friend and her partner have been given a free home to live in, the supports they need to live, and the warm embrace of an expansive and loving family. My friend has been in awe of the way she has felt accepted as another daughter.

What does this have to do with disability? Well, consider that if you live long enough, it’s almost a certainty that you will become disabled. Almost every single person will become at least temporarily disabled to some degree at some point in life. Disabled or not, needing the support of others is just a fact of life. Disability terrifies us because we live in a meritocratic society that worships individualism and denies the reality that no one is ever truly independent. Disability is what shatters the illusion of independence. It is these harmful, unrealistic beliefs that make the fact of disability so terrifying, but it doesn’t have to be this way.

The most sensible thing an able-bodied person can do to protect their future self is to advocate right now for a society of care, of acknowledged interdependence, of cooperation. Perhaps you’ll never get to see the direct connection — like my friend who couldn’t see the value in her partner sending money home to a family in Mexico he didn’t know — but what we put into the world, together, does come back to us, whether we see it or not. Individualism has severed the essential social contract that protects all of us at every stage of life. We are all suffering from it. We need to value collective care and mutual responsibility again.

From individual change to structural reform

Apart from changing our individual attitudes, we will need to address structural factors, as well. To give just one example, most cities in the U.S. are designed in such a way that makes residents heavily car-dependent. This increases the likelihood of car accidents, which can lead to disabilities. The reasons people are distracted while driving — from long working hours and commutes to cell phones and lack of quality sleep — are often overlooked in discussions about fault and responsibility.

Additionally, the failing social safety net in the U.S. often adds to the burden of those who get sick or injured rather than helping them. Contract and gig work with no benefits, for-profit car insurance and healthcare systems, lack of access to affordable housing, and myriad other failures of the neoliberal state leave individuals and their families financially devastated, further exacerbating their suffering. The problems are many, and it will take a great deal of time and effort to address them, but we have to start somewhere.

We can start by questioning our own biases and judgments. We can make a conscious effort to treat others with kindness and empathy, without seeking to determine whether they are worthy or unworthy of our support. We can interrogate the echoes of the long-dead Puritans who shaped American culture and dismantle the structural factors that contribute to suffering and inequality.

As Zoe Bee concludes in her video essay:

This kind of change will take a concerted effort from the difficult and much constrained work of organization and mobilization... So don’t get discouraged if it takes a while. No one changes their mind immediately, and people very rarely change their minds in front of others. Yet history consistently shows that meaningful social progress is achievable through persistent advocacy, community engagement, and thoughtful policymaking.

Dismantling meritocracy is going to require us to have the courage to question norms, confront our own discomfort, and advocate for structural change. But a fairer, more equitable society isn’t just possible — it’s necessary, because meritocracy is killing us. By working together, we can build a future where everyone thrives, where every individual is inherently valued and respected….

We’re not stuck living in this meritocratic myth. We just have to be brave enough to see that for ourselves.

A society demonstrates true strength when it values and includes all its members, while a society that enables and denies systems that exclude members based on arbitrary standards of ‘normal’ shows its weakness. Let’s make society strong again.

JD Goulet (they/she) is a high-life, low-tech, American-born neuroqueering iconoclast writer. They were a former U.S. politician, Planned Parenthood board member, and secular movement leader, and are now an exiled immigrant living in Portugal. Throughout their career, they have been an educator and champion for inclusion and wellbeing, especially at the intersection of disability, neurodiversity, sexuality, gender, and class. Their bylines appear in Harvard Business Review, Tumbleweird Magazine, Solarpunk Stories, and various regional publications.

Dear reader, I want you to know that I have mixed feelings about even writing essays like this lest someone try to use it as an inspiring example of overcoming adversity. “Look, that professional writer kept writing after her stroke, and now she’s got something even more interesting to write about… her disability!”

Seriously, this is a trap that is driving me even more towards the edge of sanity… please know that to try to prevent triggering another migraine, this single essay was written in bursts over a period of many days. It was an exhausting cognitive slog. I still struggle to tell whether it will make sense to anyone else; and more often than not, I’m homebound and miserable because of my symptoms.

That said, I welcome you to buy me a coffee (https://ko-fi.com/D1D8HEO8R) if you appreciate what I’ve written, because the reality is that I’m disabled and unemployed, and the chaotic U.S. government sure ain’t making it any easier or faster to get the disability claim I filed nearly two years ago approved, if ever.

— JD Goulet

References

- https://youtu.be/X6RcWUeHDk8

- https://archive.is/zSH2z

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ableism#Supercrip_stereotype

- https://web.archive.org/web/20180305202445/http://www.cw.ua.edu/article/2016/12/inspiration-porn-a-look-at-the-objectification-of-the-disabled-community

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Survivorship_bias