In 2021, a dog died after drinking water from the Columbia River. Toxic algae was suspected as the cause. In that same period, two more dogs died after swimming in the river. After these events, the Benton-Franklin Health District (BFHD) started monitoring the algae growth more closely. Continued sampling in 2021 and 2022 found additional cases of high toxin levels. In 2022, Leslie Groves beach area was closed to the public for two weeks due to toxin levels that were higher than the Washington State Department of Health recreational limit.

More resources allocated

Jim Coleman from the BFHD is a climate change effects specialist, leading the program to monitor algae bloom in the Tri-Cities.

He is monitoring 12 sites at the Columbia River by taking samples every second and fourth Monday of the month. The Environmental Protection Agency and the United States Geological Survey are monitoring and sampling multiple areas along the river as well.

Algae is beneficial in most cases

Algae comes in various different forms, and they are very helpful in the ecosystem, turning carbon dioxide into oxygen through photosynthesis. However, due to waters containing more and more nutrients (from runoff and potentially from weather changes like increased temperature), algae numbers have increased over the last years. Only a limited number of them can produce toxins; currently, it is not clear why. Ongoing research may reveal more answers in the future.

What we do know is that the toxins — produced by a special type of algae called ‘cyanobacteria' — thrive in warm, slow-moving, nutrient-rich water (specifically containing nitrogen and phosphorus).

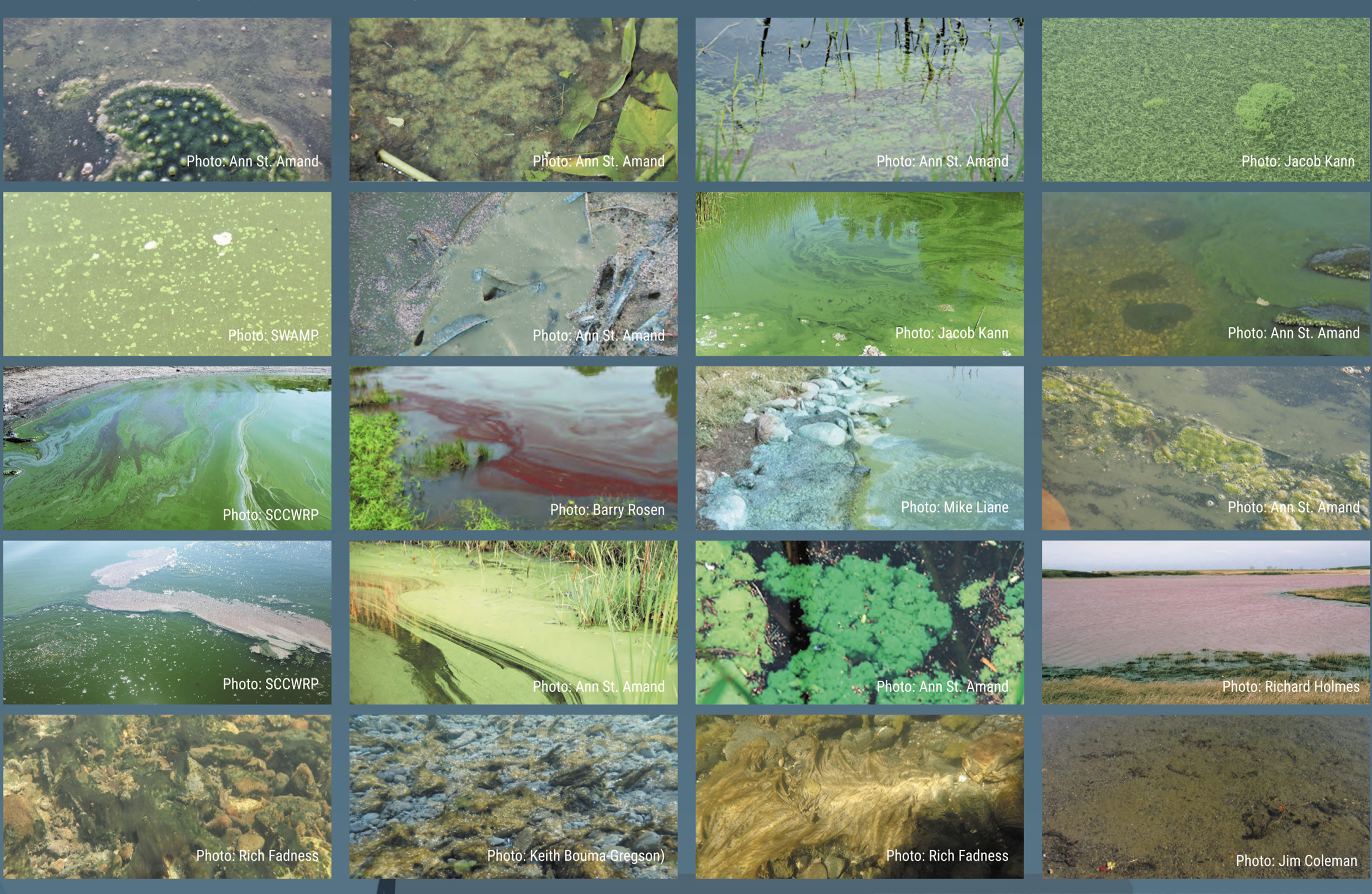

Different forms of ‘cyanobacteria’

I talked to Coleman to get more information about the dangers and causes of toxic algae in our river. According to him, there are two types of algae to consider:

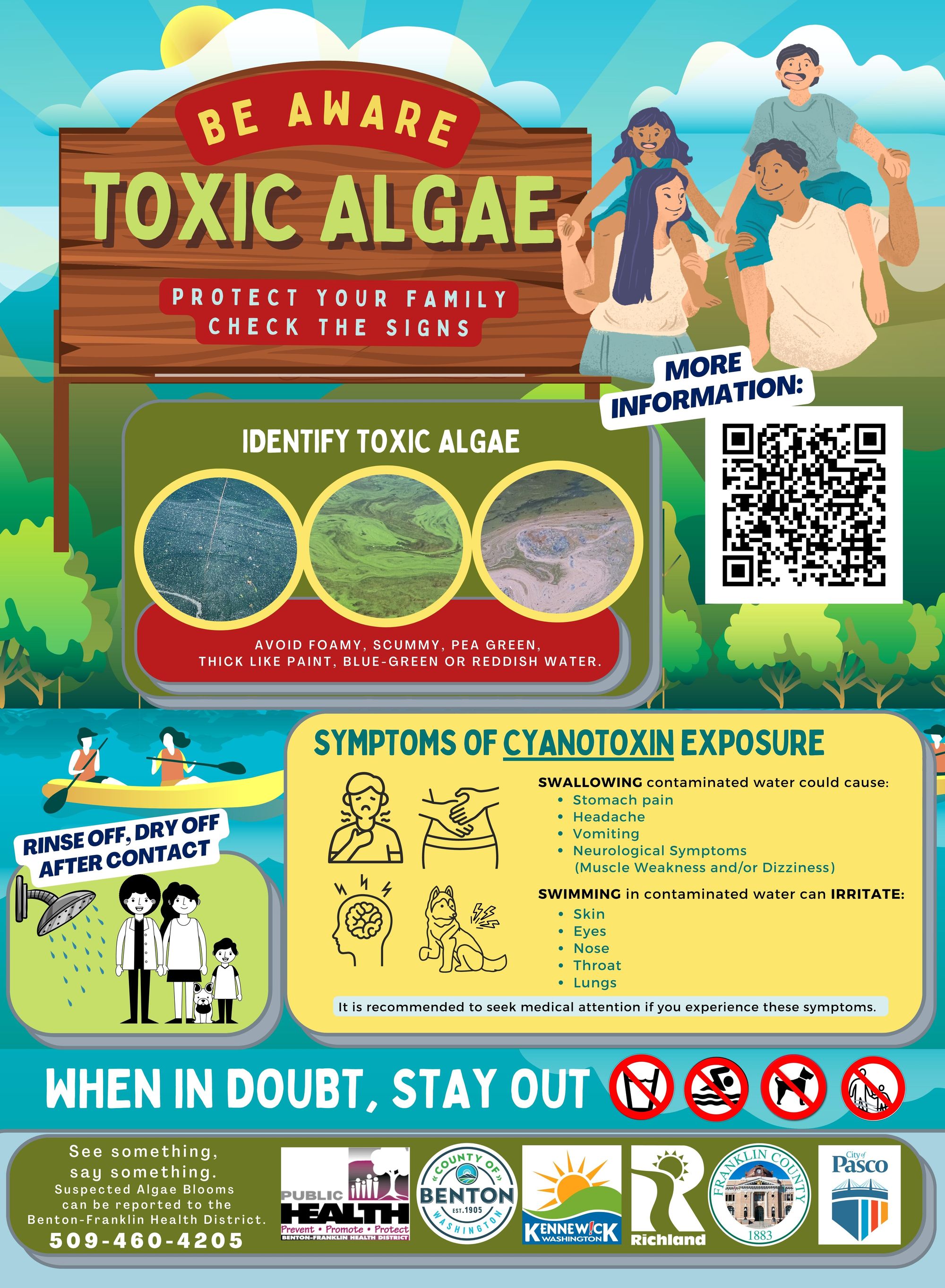

1. Planktonic: these are the very obvious suspended algae accumulating at the top of the water’s surface. These usually create a pea-green color in the water referred to as a ‘bloom’.

2: Benthic: these are the algae growing on the bottom of the river (on the floor or on structures). When these grow, the sediments may be green or brown, but the water stays relatively clear.

Toxic algae can be present in relatively clear water

The toxic algae found in Richland are thought to be benthic. Where they were found, the water was relatively clear, with some algae noticeably growing on the bottom.

When is it a big deal?

When taking drinking water from surface water like the Columbia River, the toxins entering the treatment plant can be resistant to regular treatment with chlorine, and this can impact our drinking water. However, Tri-Cities’ drinking water has never exceeded the state guidelines of toxin levels for drinking water.

So far in Benton-Franklin Counties, there have not been any confirmed human illnesses due to algae toxins, but cases may go unnoticed since some symptoms may mimic other illnesses. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a report wherein 14 states had a total of 63 human cases of suspected algae-borne toxic illness. Coleman pointed out that human symptoms resemble food poisoning, so he said it most likely is underreported.

These toxins have a bigger impact on pets. Several cases of pets suffering from toxic illness from algae are reported on a yearly basis throughout the country.

What causes an increase in algae growth?

Worldwide, the frequency and duration of toxic blooms have increased in recent years.

Since toxic algae love warm, nutrient-rich, slow-moving water, we should expect climate-change-driven heat, drought, and low flows to result in more algae in the Columbia River.

Climate change coupled with excessive nutrient pollution may cause more intense and frequent algae blooms. According to the Columbia Riverkeeper, Columbia River dams that slow flows and increase water temperatures are significant contributing factors to these changes in algal blooms as well.

Nutrient loading can be due to agricultural runoff. Some types of nutrients, like phosphorus, can accumulate at the bottoms of lakes and rivers, contributing to algal growth for long periods of time. According to the Franklin County Conservation District, current agricultural practices are far better than they were in the 1950s–1960s, but it is sometimes difficult to recover from a nutrient overload that may have occurred in the past.

How to prevent the increase of algal blooms

According to the Columbia Riverkeeper, to prevent toxic algal blooms, we need to reduce nutrient inputs from industrial chemicals, fertilizers, manure, and human waste; increase water flow; address the temperature impacts of dams; and curb climate change. Even small changes from individuals can help, like always remembering to pick up pet waste and adopting practices to reduce nutrient pollution (e.g. taking care to not over-fertilize).

Reducing stormwater runoff and protecting riparian habitat helps too, because riparian vegetation can remove excess nutrients and sediment and acts as a buffer for runoff.

The Riverkeeper recommends increasing monitoring and developing better communication systems to protect people, pets, wildlife, and the environment.

Don’t be afraid of the river

The Columbia River is a real asset for our community, and we all love boating, fishing, rowing, paddle boarding, canoeing, and all other recreation on the water. Algae in the river have been there for a long time, and according to Coleman, the overall threat to humans is very low.

Nevertheless, stay informed, and be aware if you have symptoms after swimming in the river. If you develop symptoms like stomach pain, headache, vomiting, or neurological symptoms (muscle weakness and/or dizziness), seek medical attention. If you suspect that you may have been poisoned by toxic algae, call the Poison Center Hotline (1-800-222-1222). If you suspect toxic algae blooms, you can report those to the Benton-Franklin Health District: 509-460-4205. You can find more information on the BFHD or Washington State Department of Ecology website.

Sources:

https://www.bfhd.wa.gov/programs_services/water/toxic_algae_blooms

https://www.cdc.gov/habs/data/2020-ohhabs-data-summary.html

https://www.columbiariverkeeper.org/columbia/harmful-algal-blooms-faqs