The iconic sagebrush is facing a silent threat: the expanding footprint of humans, deciding to use land for economic benefit. The repercussions are vast and far-reaching. It’s not just about losing a distinctive shrub; it's a complex domino effect that impacts the entire ecosystem.

Sagebrush isn't just a backdrop; it's a crucial support system for local wildlife. Beyond that, its deep roots play a key role in holding soil together, preventing erosion that could lead to environmental degradation.

A different type of forest

Sagebrush steppe stretches across 165 million acres of the American West, creating a distinct gray-green landscape. It is home to more than 350 species. A few animals can eat sagebrush, and those that do — for example, the sage-grouse, the pygmy rabbit, and the mule deer — depend on it. Its characteristic smell is primarily attributed to the presence of essential oils containing various aromatic compounds like terpinene, limonene, cineole, and camphor.

A sagebrush has a common lifespan of 50–100 years, although there are some that can live as long as 150 years.

Resilience we need

Sagebrush has a deep root system that helps it access water in arid environments, making it resilient during periods of drought. It can thrive in these harsh conditions where other vegetation might struggle.

A healthy shrub steppe ecosystem including sagebrush can help fight wildfires in a few ways. It acts like a barrier, slowing down the fire's advancement, and it prevents invasive species from entering. Many wildfires increase in intensity because of invasive species.

After wildfires, sagebrush has mechanisms for recovery and regeneration. However, an increase in the frequency or intensity of wildfires can exceed the adaptive capacity of sagebrush ecosystems, contributing to their decline.

An estimated 80% of historic shrub steppe in Washington State has been lost or degraded to development and agriculture since the arrival of non-native settlers. A 2022 U.S. Geological Survey report shows that half of the original sagebrush ecosystem has been lost at a rate of approximately 1.3 million acres each year in the last two decades!

Why conservation efforts are challenging

With this rapid decline of sagebrush shrub steppe, protecting remaining shrub steppe habitats is more important than ever. Many efforts to replant sagebrush have proven to be unsuccessful, due to its intricate ecosystem requirements and interdependencies. A Colorado State University report from the 1970s found that all test sites with various degrees of disturbance had poor regrowth of sagebrush.

The sagebrush relies on a complex ecosystem that, once disturbed, is not easy to replicate. Fungi in the soil (the so-called ‘mycorrhizal fungi’) play a role in the ecosystem where sagebrush thrives. These fungi are important for soil structure and the ability for the plant to get its minerals.

In disturbed soil areas, invasive species like cheatgrass, which doesn’t rely on the fungi, will establish first. Once entered in the system, they will then affect the composition of the fungi or cause it to decline. Therefore, these invasive species negatively impact the chance of sagebrush (a slow grower) to reestablish.

The exact relationship between mycorrhizal fungi and sagebrush is still not completely understood, and researchers like Dr. Catherine Gehring (Arizona State University) and Dr. Richard Miller (Oregon State University) continue to find clues on how to better restore sagebrush habitat, keeping these fungi in mind.

Ongoing local restoration efforts are initiated by the Native Plant Society, Tapteal Greenway, and the Washington Fish & Wildlife Service. The page on the right shows recent efforts.

Mass extinction looms

The greater sage-grouse — the bird that the Lewis and Clark Expedition called the ‘heath cock’ or ‘cock of the plains’ — once numbered in the several millions, as opposed to the 200,000 estimated today. In Washington State, the sage-grouse, with its unique courtship displays, is almost extinct. There are very few populations scattered around, including on the Yakima Firing Center.

The bird requires large areas of shrub steppe habitat, and its food and livelihood depend on the sagebrush. It hides its eggs underneath it, and every spring, if possible, it returns to the same sagebrush mating ground (called a lek). Scientists generally have agreed that as the sage-grouse goes, so could go the pygmy rabbit, the pronghorn elk, the golden eagle, the mule deer, and countless other animals who are also reliant on the same habitat.

This land is a part of us

The sagebrush holds cultural importance for various Indigenous communities. Besides its practical use for medicine, basketry, and rituals, the sagebrush represents a spiritual tie to the land, embodying a timeless relationship that underscores the importance of preserving both cultural heritage and the fragile ecosystems where sagebrush thrives.

Sources:

ChatGPT, Wikimedia Commons

SateSTEP (Sagebrush Steppe Treatment Evaluation Project) sagestep.org

Sage-grouse pub: https://wdfw.wa.gov/publications/01118

sciencebase.gov/catalog/item/62d57e89d34e87fffb2dda62

nativememoryproject.org/plant/big-sagebrush

Some initiatives highlighting sagebrush restoration efforts include:

Native Plant Society

The Washington Native Plant Society planted 400 sagebrush at Horn Rapids Park in November 2023 and 50 in a small part of Horse Heaven Hills around the McBee trailhead. Sagebrush seeds have been spread in various places around McBee grade in hopes of reintroducing sagebrush into this relatively healthy shrub steppe habitat.

Mickie Chamness: mickiec@charter.net

US Fish & Wildlife Service

The USFWS is planting 10,000 sagebrush this December and January on the Rattlesnake mountain, portion of the Hanford Reach National Monument.

Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife Service planted 3000 sagebrush and riparian plants near Prosser in a portion of the Sunnyside-Snake River Wildlife Management area that burned in the summer of 2023.

McNary office of USFWS (Burbank): mcriver@fws.gov

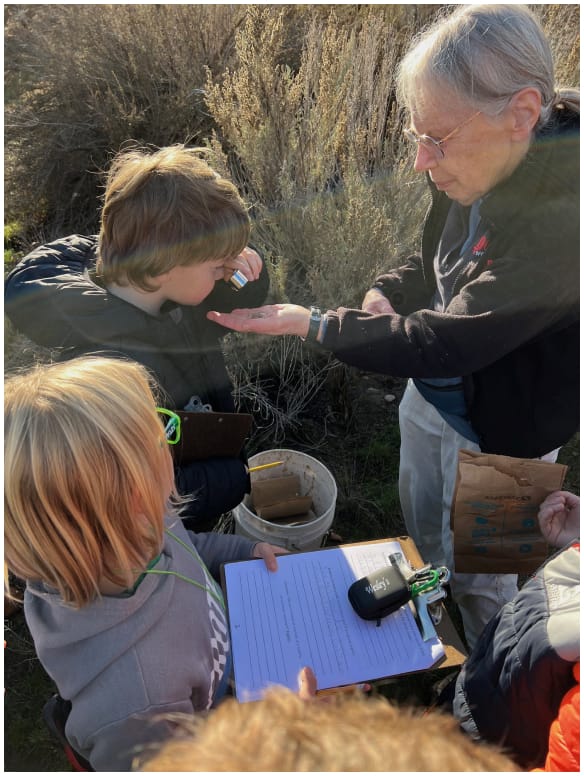

Wiley Elementary School program, Richland

Lindsay Gailey’s 4th grade class visited Leslie Groves North (a city park in North Richland) on four seasonal field study trips to learn about shrub steppe habitat and participate in water quality data collection and analysis. This field study experience has evolved thanks to a partnership between members of the Audubon Society, Native Plant Society, and Tapteal Greenway; Debbie Berkowitz, Ernie Credford, Kelsey Kelmel, and Dirk Peterson; and 4th grade teacher, Lindsay Gailey.

During their winter trip, the students worked to collect sagebrush seeds, learning how to locate and respectfully collect the seed. Later in the spring, the students worked to plant the seeds in pots in their classroom. The sagebrush starts were cared for by their teacher until the following fall. At that point, the students and their parents were invited to culminate their field study experience on a Saturday afternoon by planting their native plants in a habitat area in need of restoration

Lesson plans to save the shrub steppe are available on the website of the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife: wdfw.wa.gov/get-involved/environmental-education-curriculum/lesson-plans/saving-shrubsteppe