It’s time to start telling the truth about systemic racism in the USA. I’ve spent the last few months reading about redlining and the relationships Black Americans, in particular, have with the natural environment, and environmental activism.

The truth is upsetting. The complete lack of education about how racist practices have been allowed to continue is maddening. We could have been the America we purport to be—with liberty and justice for all—a long time ago except for one persistent, pervasive, ongoing thing. RACISM.

Did you know that after the Emancipation Proclamation, Freedmen (emancipated former slaves)—especially those who fought for the Union—were granted land? They initially were given ‘40 acres and a mule’ from the land that had been confiscated as part of the spoils of war. But former plantation owners (traitors who were pardoned) pressured Andrew Johnson to reverse the order. Less than a year after becoming landowners, Freedmen were forced back off the land.[1]

The Homestead Act encouraged folks to settle the west. It was suggested that transportation be provided to move Freedmen out west to participate in the Homestead Act, but Johnson vetoed every proposal. A separate Southern Homestead Act did avail Freedmen about 6,500 claims to homesteads, and about 1,000 of these eventually resulted in property certificates. But before much land was distributed, the law was repealed in June 1876.[2]

As was pointed out in Black Faces, White Spaces by cultural geographer Carolyn Finney, at roughly the same period, John Muir and others (like Gifford Pinchot) began suggesting we set aside vast tracts of land to protect nature and natural wonders. Don’t get me wrong, I love Yosemite and Yellowstone and am so thankful for their foresight. But it is disappointing to contemplate that land was protected essentially for aesthetics before it was made available to the people, who in many cases, built this country.

“While Pinchot and Muir explored, articulated, and disseminated conservation and preservation ideologies, legislation was being enacted to limit both movement and accessibility for Aftrican Americans, as well as American Indians, Chinese and other nonwhite peoples in the United States.” (Finney, 2014, p. 37)

Environmentalists also played into the persistent racial divisions all along the way. Whether intentionally or not, we did not make Black people feel safe or welcome in America’s ‘great outdoors’. The Wilderness Act set aside even more land in 1964—the same year the Civil Rights Act was passed.

Some environmental groups are making real efforts to remedy these historic wrongs, adding BIPOC their boards of directors and changing practices in the field. Some are still working to become anti-racist. And others are likely in denial.

While our nation’s first environmental groups focused on protecting habitat, other groups began forming in the 70s and 80s to focus on human health and pollution.

As most people know, Black and Brown people are disproportionately impacted by proximity to industrial sites, railroads, and roads (many segments of the interstate highway system actually destroyed Black neighborhoods). Black people were only allowed to buy in certain areas due to federal housing policies.

Richard Rothstein in The Color of Law pointed out that we’ve had public housing in the US for a very long time. “The federal government first developed housing for civilians in WWI… when it built residences for defense workers near naval shipyards and munitions plants. Eighty three projects in 26 states housed 170,000 white workers and their families. African Americans were excluded, even from projects in northern and western industrial centers where they worked in significant numbers.”

Even in places we think of as progressive today, like San Francisco, regulations were put in place to prevent Blacks and other ‘undesirable’ populations from moving into new neighborhoods. But what is perhaps more astonishing is that cities and neighborhoods that were actually diverse and mixed were forced to segregate by federal policies.[3]

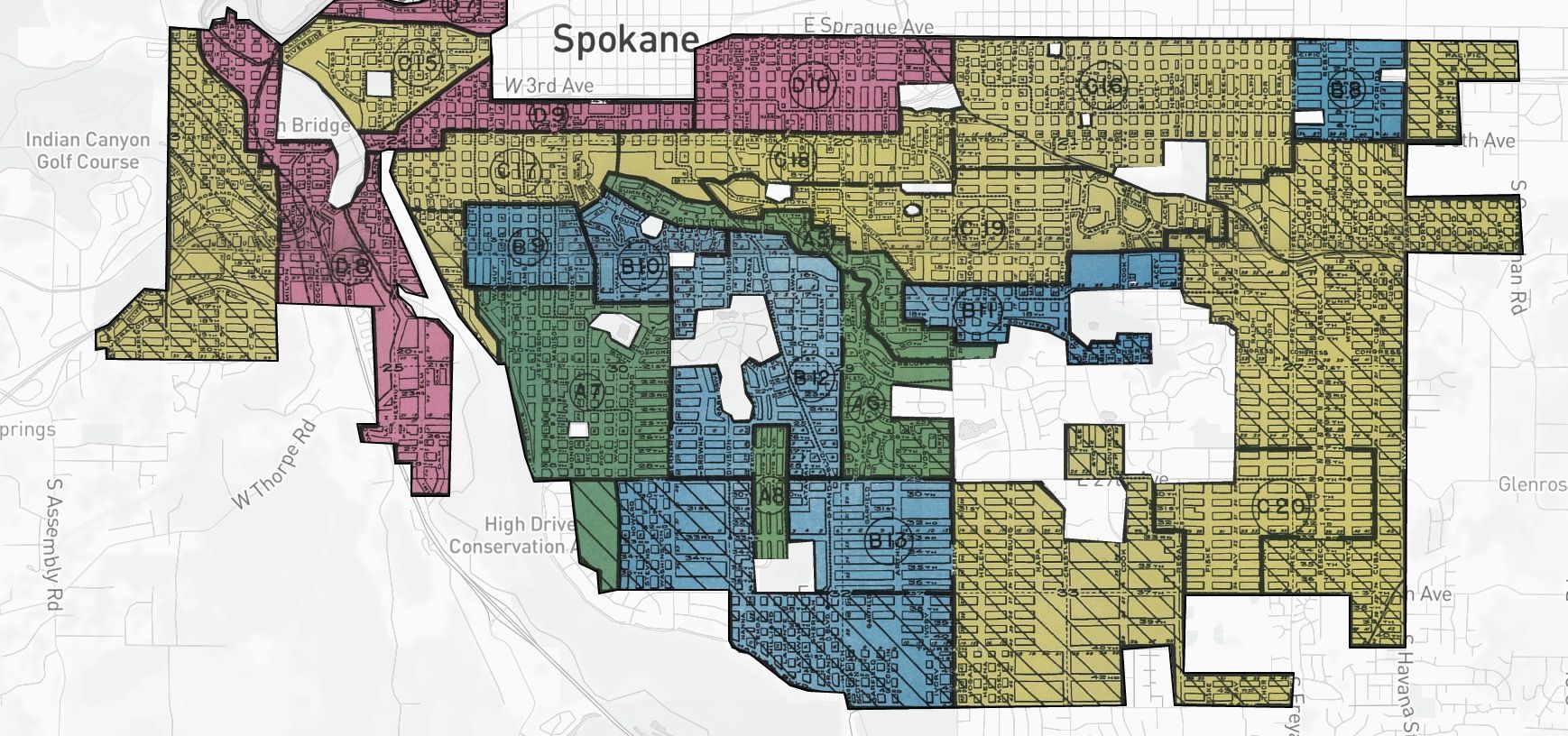

During WWII and Roosevelt's New Deal, discrimination continued. Not only were government-built homes segregated, government-insured loans were, too. The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) from 1933 to 1977 maintained the redlining maps that graded cities based on racial (as well as national, e.g. Italian and Irish) characteristics. The Federal Housing Authority (FHA) mortgage insurance available to white people wasn’t available to Blacks, so banks wouldn’t take the risk of loaning to them.

Rothstein states, “African Americans were unconstitutionally denied the means and the right to integration in the middle-class neighborhoods, and because this denial was state-sponsored, the nation is obligated to remedy it.”

Search ‘mapping inequality’ to see for yourself. While not all cities are shown, Seattle, Tacoma, Spokane, and Portland are listed.

Perhaps most shocking are the blatant comments about race and class that accompanied the maps. The government agency didn’t even attempt to hide their disdain. Each map includes ‘clarifying remarks’ such as: “Three highly respected Negro families own homes and live in the middle block of this area facing Verde Street. While very much above the average of their race, it is quite generally recognized by Realtors that their presence seriously detracts from the desirability of their immediate neighborhood.” (Tacoma, D1) [4]

Another remark states: “This might be classed as a 'Low Yellow' area were it not for the presence of the number of Negroes and low class Foreign families who reside in the area.” (Tacoma, D7)4

Portland’s clarifying comments are also blatantly demeaning.

Where Portland’s Rose Quarter is now (they tore down a mixed neighborhood to build it, by the way), the clarifying remarks include “...Subversive population which included colored races as shown above, also consists of a relatively large proportion of low class foreign born of many races…”[5]

Reading the clarifying comments, you can see that non-white neighborhood inhabitants were spoken of as having “infiltrated” the neighborhoods. They were labeled ‘subversive races’.

However according to the Brookings Institution, “Examination of the HOLC redlining maps, numbering over 200, reveals that approximately 11 million Americans (10,852,727) live in once-redlined areas, according to the latest population data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (2017). This population is majority-minority but not majority-Black, and, contrary to conventional perceptions, Black residents also do not form a plurality in these areas overall. The Black population share is approximately 28%, ranking third among the racial groups who live in formerly redlined areas, behind white and Latino or Hispanic residents.” [6]

Regardless, the forced segregation by the government “...prevented generations of families from gaining equity in homeownership or making improvements to homes already owned.” (Brookings)

Of course, the federal government wasn’t the only problem. Restrictive covenants nationwide specifically stated that homes couldn’t be sold to People of Color. A neighborhood in Berkeley tried to evict a prominent Black doctor and WWII Veteran by asserting their covenants requiring “pure Caucasian blood”. They did lose due to a Supreme Court decision in 1948 forbidding state courts to enforce such restrictive covenants. (Rothstein, p. 81)

How we solve this problem remains to be seen. Rothstein suggests several ideas. The Brookings article shares the plans of then presidential candidates Harris, Warren, and Buttigieg for starting to fix the problem.

The Biden-Harris campaign page contains detailed plans to remedy housing inequalities. It states generally:

“As President, Joe Biden will invest $640 billion over 10 years so every American has access to housing that is affordable, stable, safe and healthy, accessible, energy efficient and resilient, and located near good schools and with a reasonable commute to their jobs.” [7]

Welcoming Black and Brown people into the outdoors, and ensuring they have access to safe, affordable neighborhoods will not be easy, but it is necessary.

Fixing this sad part of our history is critical to realizing the promise of liberty and justice for ALL!

Ginger Wireman is an environmental educator teaching about Hanford cleanup in her day job. She is an active volunteer working to dismantle systemic racism in urban planning, focusing on the intersection of environmental justice and climate change because BIPOC are disproportionately harmed by climate injustices.

Instagram: ginger_sage_sky

Image credit: Map created by © OpenStreetMap contributors and distributed under the Open Database License (https://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright)

[1] Carolyn Finney (2014) Black Faces, White Spaces

[2] Paul W. Gates (1940) “Federal Land Policy in the South, 1866-1888,” Journal of Southern History, 6, 310-315.

[3] Richard Rothstein (2017) The Color of Law

[4] Mapping Inequality: Tacoma, WA

[5] Mapping Inequality: Portland, OR

[6]brookings.edu/research/americas-formerly-redlines-areas-changed-so-must-solutions

[7] joebiden.com/housing

For more information about the link between shade trees and redlining, visit: www.treetriage.com/tree-removal/link-between-redlining-and-shade-trees