The Necronomicon by Kitab al-Azif (Abdull Alhazred) is purported to be the original Arabic title of the mythological grimoire often referred to as The Book of the Dead. This grimoire is first identified in Lovecraft’s 1924 short story “The Hound” and recurs in many of his other writings (and the writings of the many authors who wrote derivative works). The Necronomicon is the cornerstone of the Cthulhu Mythos.

I have a copy that indicates it is the John Dee translation. So, who is John Dee and what does he have to do with The Necronomicon? I am slightly acquainted with the Elizabethan John Dee, and I believe if someone were to have translated a grimoire like The Necronomicon, it might have been John Dee. If you’ve never heard of him, that is not surprising since he seems to be relatively unknown, although occasionally he is referred to in fantasy/horror/occult fiction. He is also recognized by many people (particularly those with interests on the magic/paranormal side) as a historical authority on the occult, particularly Enochian (angelic) language. His large Elizabethan library contained many manuscripts or copies of manuscripts, some of which he copied himself.

John Dee was an Elizabethan who was born in 1527 and died in 1608. His father was a courtier to Henry VIII. He lived an eventful life, although most histories of the period don’t mention him. However, the 1891 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica has a short writeup on him, and David Harris Willson’s A History of England does indicate that John Dee was a mathematician and geographer who supported the potential for the Northwest Passage.

John Dee was married three times (with each wife passing away) and had eight children, several of which died before him. Dee was one of the original fellows of Trinity College in Cambridge, and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1542. He was a mathematician and lecturer, and he wrote a preface to a book addressing the mathematics of Euclid.

Dee was arrested in 1553 and charged with casting a horoscope for Queen Mary, possibly because it projected Elizabeth as the heiress to Queen Mary. He was released in 1555 and recharged with heresy, but Queen Mary gave him a pardon the next year. When she died, at the request of John Dudley, Dee chose the most ‘auspicious date’ for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth, and he became court astrologer and scientific advisor. He was often referred to as ‘The Queen's Conjurer’.

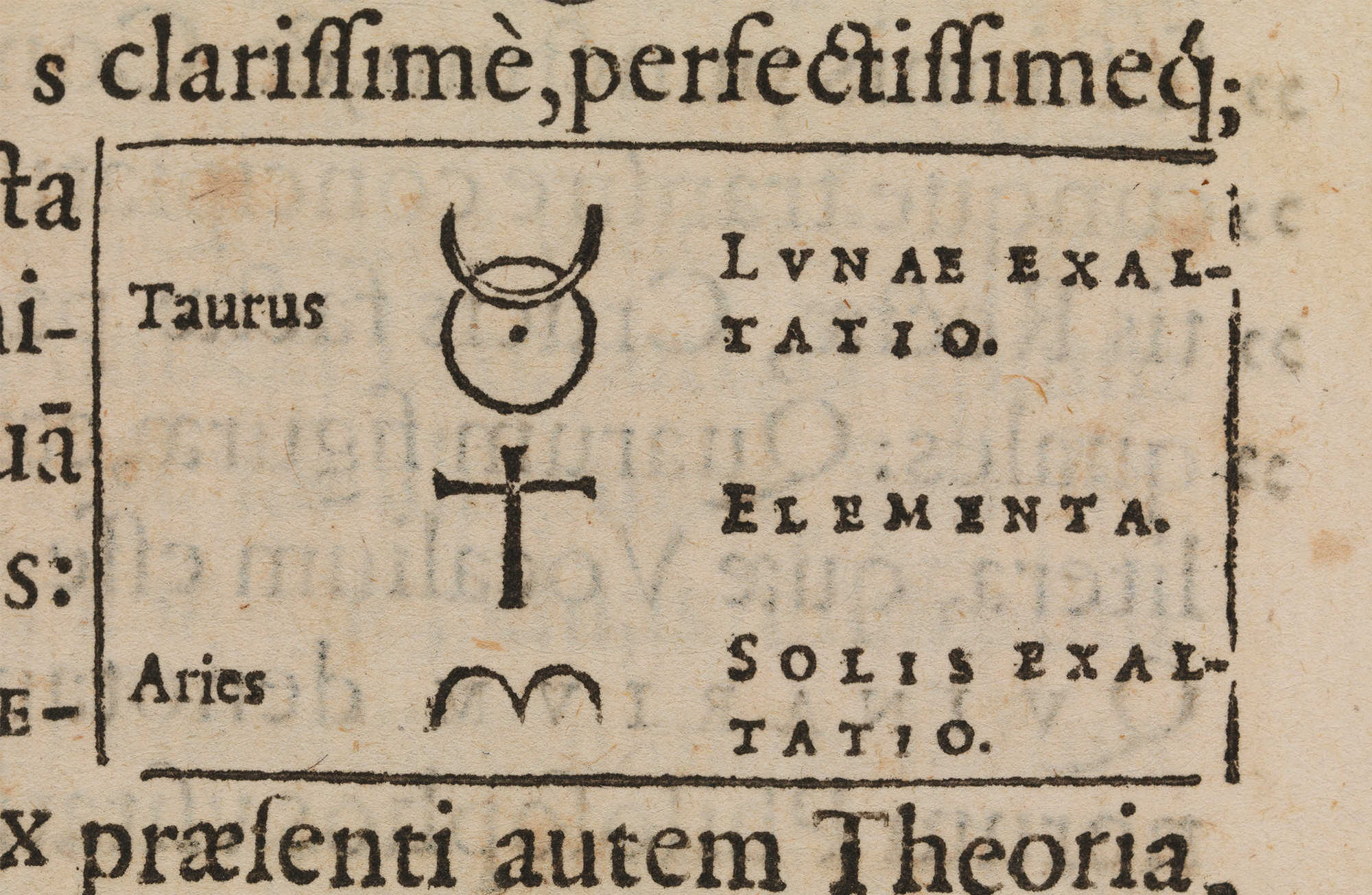

Although Dee joined the Worshipful Company of Mercers (a merchant and trader association) and was exonerated of heresy, charges related to heresy and occult practices would follow him throughout his life. Despite this reputation, Dee was an extremely religious Christian influenced by the Hermetic, Platonic, and Pythagorean doctrines common at that time. He believed that reality was based on the perfection of mathematics. His first astrological physics/natural philosophy book was Propaedeumata Aphoristica (1558). Dee also wrote Monas Hieroglyphica (1564), an exhaustive cabalistic discussion of a glyph of his design that said expressed unity of creation.

During his time as Queen Elizabeth’s advisor, Dee converted to the Church of England and found favor with the nobles supporting Elizabeth, including William Cecil, and was appointed the Royal Advisor of Mystic Secrets in 1564. He provided technical support, navigation assistance, and political support for England’s voyages of discovery. He also proposed that England adopt the Gregorian calendar, but it was determined to be too papist by Elizabeth’s court and was not adopted until 1752. He was involved in the introduction of the mathematical signs (+, -, x, and ÷) by including them in his introduction to Sir Henry Billingsley’s book: The Elements of Geometrie (1570).

In the 1580s, Dee became more interested in the occult, particularly scrying, because he wanted to talk to angels. He apparently owned an Aztec obsidian mirror he used for this purpose. In 1583, Dee published Liber Loagaeth Or Mysteriorum Liber Sextus et Sanctus (49 Gates of Wisdom and Understanding) and De Heptarchia Mystica (On the Mystical Rule of the Seven Planets), both of which address occultist considerations. Dee also became involved with Edward Kelley (aka Edward Talbot), an occultist supposedly good at scrying, as Dee was purportedly unable to successfully use his own scrying devices.

Years before, Queen Mary had turned down Dee’s proposal for the founding of a national library, so Dee had begun expanding his own library in Mortlake. Dee said he had a library of 3000 books in what became the greatest library in England. Dee and Kelly lived a nomadic life throughout Central Europe during this time. In 1587, Kelly had a revelation that they should share everything, including wives, which apparently led to friction between them. In 1589, Dee returned to his home at Mortlake in England and broke from Kelley. Upon his return, he found that there had been theft and destruction of much of his library and scientific equipment by a mob in his absence.

I believe that if the mythological Necronomicon had existed during John Dee’s life, he would have had a copy in his library, and probably would have been likely to have translated it. However, given the likelihood that it might have been considered anti-Christian, and that such activities could get you hanged or burned, perhaps not. Dee’s reputation as an occultist, astrologer, alchemist, and scientist simply made it easy to name him as translator of The Necronomicon. He has become a kind of historical fiction character — a sorcerer, alchemist, astrologer, and occultist in science fiction, fantasy, horror, and historical fiction stories.

References:

- curiousarchive.com/john-dee-necronomicon

- Dr. John Dee (edited by Nebo)

- The Necronomicon, the John Dee translation

- John Dee, Elizabethan Mystic and Astrologer, Hort, G. M., Dr. William Rider & Sons

- thoughtco.com/john-dee-biography-4158012

- livescience.com/john-dee-spirit-mirror-aztec

- mentalfloss.com/posts/john-dee-elizabeth-court-astrologer-facts

- history.co.uk/articles/the-magical-life-of-dr-dee-queen-elizabeth-i-s-royal-astrologer

- hellfireclubbooks.com/product/enochiana-vol-1-pts-1-2

Steven Woolfolk is the owner of Xenophile Bibliopole & Armorer, Chronopolis, a rare books specialty bookstore in Richland, online at Xenophilebooks.com.