Images courtesy of the author.

How to sell a scientific rumor

This article was originally published at https://www.youcanknowthings.com/do-dogs-cause-autism, and is reposted here with permission.

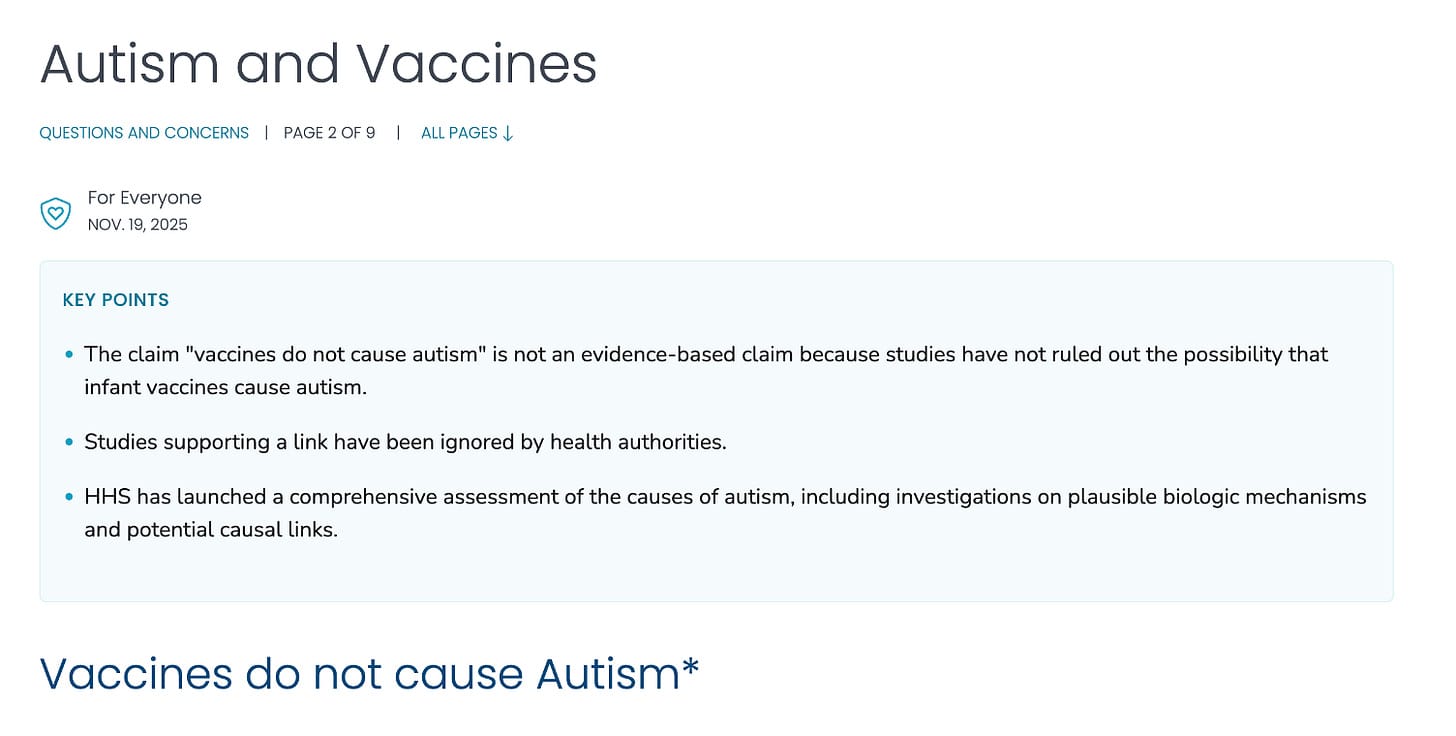

On Wednesday RFK Jr.’s CDC updated their website to claim that “vaccines do not cause autism” is not an evidence-based claim because studies have not definitively ruled out the possibility.

RFK Jr.’s version of the CDC website. They still kept the title “Vaccines do not cause Autism*,” with an asterisk, because RFK Jr. had promised Senator Cassidy he wouldn’t remove this language during his confirmation process.

On the surface, this may seem like a valid scientific statement. There have been dozens of studies investigating links between vaccines and autism (particularly focused on the MMR vaccine), and the high quality studies consistently show the same answer: there is no link. But have we really looked at every single possibility?

A rumor that is designed to never die

This may seem like a reasonable question, but when you zoom out, it becomes clear this framing creates a question that is designed to never be fully satisfied — a rumor that will never die, no matter how many studies are done. Here’s why.

Is it MMR?

The vaccine-autism rumor started with a single, fraudulent study back in the 1990s. This fake study of 12 kids claimed that autism symptoms started right after they got the MMR vaccine. While the study was later retracted, the rumor was born — could the MMR vaccine be causing autism?

Scientists performed larger studies, and the answer from high quality studies was consistently was no — kids who got the MMR vaccine were no more likely to develop autism than kids who didn’t. (Some lower quality studies alleged a link, largely authored by the same person with a sketchy background, whom RFK Jr. has reportedly hired — read about that story here).

Is it vaccine ingredients?

Did those studies satisfy the rumor? No — instead the goal posts shifted. Maybe it’s not the MMR vaccine specifically, but vaccine ingredients. In particular thimerosal was highlighted, which used to present in some childhood vaccines. So scientists did more studies, and no link was found between thimerosal-containing vaccines and autism. But the rumor persisted despite the science, so they even removed thimerosal from childhood vaccines all together. Did that satisfy concerns? Nope — the rumor kept growing.

Is it other vaccines?

What if it’s not MMR, but a different vaccine altogether? What about the vaccines moms get during pregnancy? So scientists did more studies. Yet like a stubborn weed, the rumor still wouldn’t die, and instead got stronger — now featured on RFK’s CDC website.

This framing sets up a question that can never be “fully” answered

After three decades of research into the topic, with shifting rumors and scientists doing more and more research trying to keep up, the rumor has still not been satisfied. Now the rumor’s demands have shifted again — “but have you studied every vaccine ever?” “What about the entire childhood vaccine series altogether?” If scientists spend the next ten years painstakingly performing these giant studies, the rumor would likely shift yet again — “ok but you added more vaccines to the childhood vaccine schedule, have you checked the updated childhood vaccine schedule?” “What about this vaccine and this specific subtype of autism? “What about parents who got the COVID vaccine?” “What about moms who got multiple vaccines during pregnancy?” “What about these specific vaccine ingredients during pregnancy?” “You’ve only done observational studies looking into these 17 questions, where are the randomized controlled trials?” We could go on and on forever like this, creating an unending list of questions and demands.

A question that can’t be “answered”

The original question: “does the MMR vaccine increase risk of autism?” was a valid scientific question. And it was studied and answered. That’s how science works — ask an answerable question, do the study, and get a result (and reproduce it).

But when the goal posts and keep shifting over and over again, it creates an unfalsifiable hypothesis — a question that is impossible to answer, because no amount of data is ever deemed “enough.” This isn’t how scientific progress happens — it’s science spinning its wheels.

Do dogs cause autism?

The phrasing on RFK’s CDC website sets up an unfalsifiable hypothesis by inaccurately suggesting that science should be able to disprove every possibility. But this is an impossible task. Science can never “disprove everything,” because you can create an infinite list of possible questions.

To show what an unreasonable standard this is, let’s dig into the question that everybody’s been ignoring and hasn’t been studied adequately — DO DOGS CAUSE AUTISM???

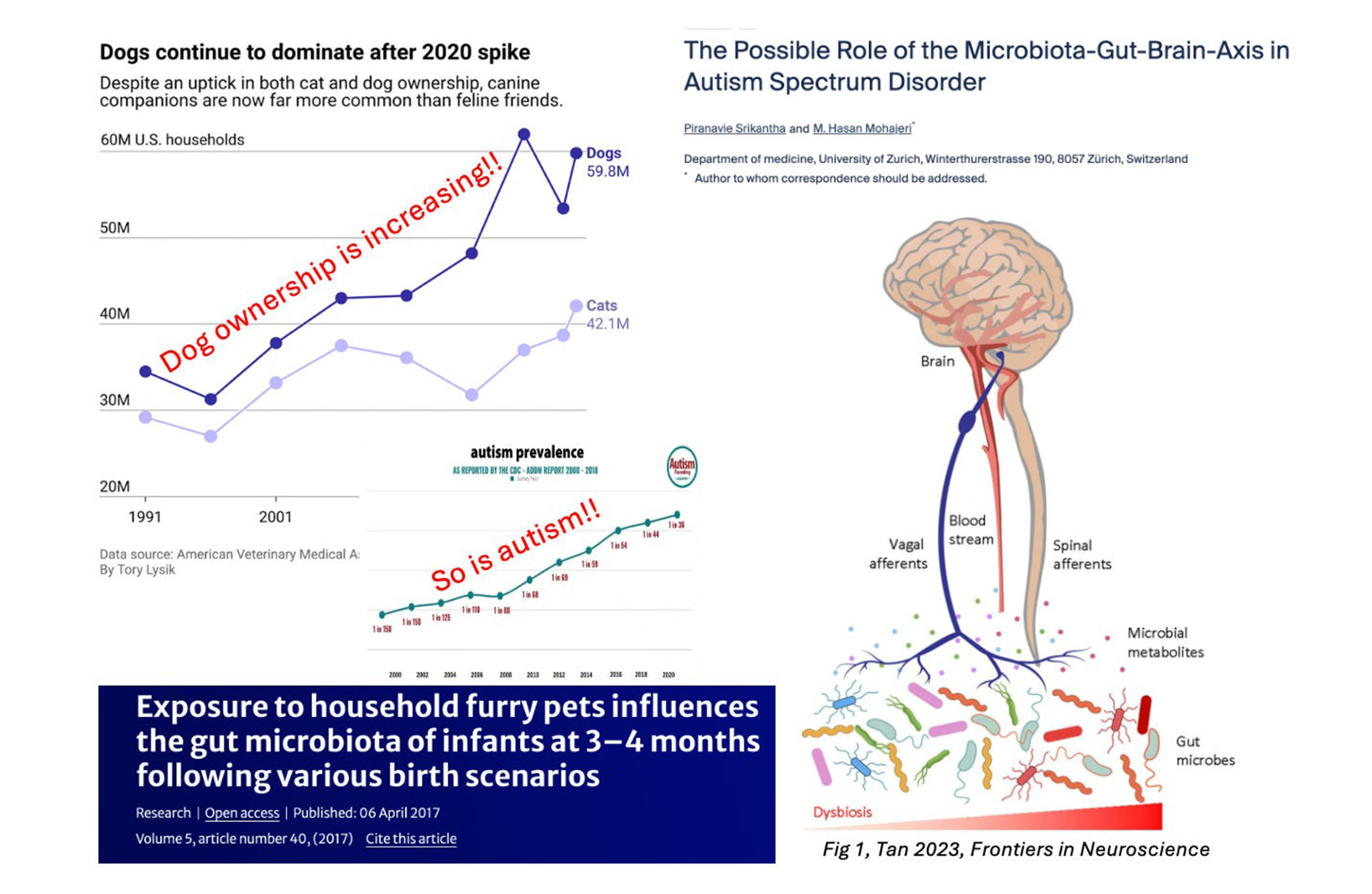

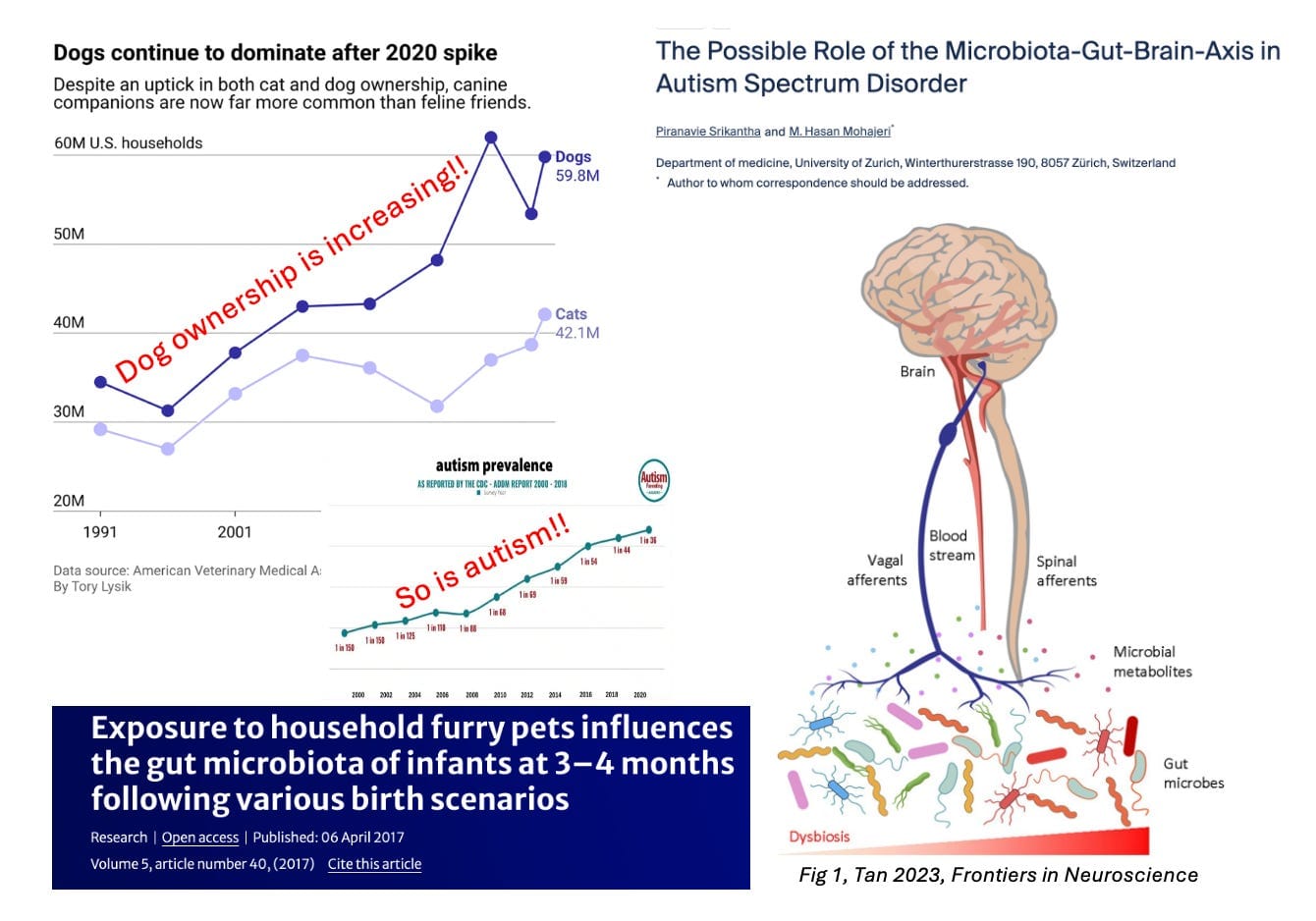

Did you know that dog ownership has increased over time, just like autism prevalence? And early exposure to dogs changes kids’ gut microbiomes? And the gut microbiome influences brain function through the gut-brain axis? And kids with autism show distinct shifts in their gut microbiomes, the very ecosystem dog exposure is influencing?? Could it be dogs are causing the autism by driving shifts in kids’ microbiomes???

At this point we could replace the word “vaccines” with “dogs” in RFK’s claim, and technically it would be accurate.

With a little scientific jargon, a few studies, and quasi-plausible link, we could do this for just about anything. Add fear and megaphone, and it creates a rumor that just won’t die. Demanding that science do the impossible — disprove every single possibility about everything — gives the rumor fuel forever. That’s what’s happening with the vaccines and autism rumor. Until we stop demanding science keep spinning it’s wheels and instead recognize the rhetorical trick for what it is, the rumor will keep going forever.

Watch Dr. Panthagani’s video “Do dogs cause autism? How to sell a scientific rumor” on YouTube, Instagram, or Facebook.

Also, dogs don’t cause autism.

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is completing a combined emergency medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things, available on Substack and youcanknowthings.com. You can also find her on Instagram and Threads. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.