Grace Lieberman is a multimedia artist whose work encapsulates a diverse art collection that explores Spanish-English fusion.

In your own words, what is your art about?

In its most playful essence, my work explores bilingual experiences and cultural intersections. But ultimately, it’s about addressing invisibility.

As background, I didn’t fully discover that [I was an artist] until 2019 when I moved to the Tri-Cities. I had been painting for years but never considered myself an artist. My work was fun but not meaningful, and certainly not mine. That changed when I returned home to Eastern Washington after my dad’s terminal diagnosis.

Spending time with my parents, I listened — really listened — to the stories about their early lives as migrant farmworkers, and first- and second-generation Americans. They shared stories of invisibility, racism, inequality, and poverty, but also of joy, resilience, and simplicity. I’d heard these stories before, but this time I listened differently, knowing they might be my dad’s last.

I also had to face my own sense of invisibility and the embarrassment I once felt about our humble beginnings. It finally hit me just how much strength it took for my parents to build a happy life despite the challenges. That truth reshaped me.

My work is now focused on addressing that invisibility, grounded in courage, guided by truth, and filled with grace for myself and others.

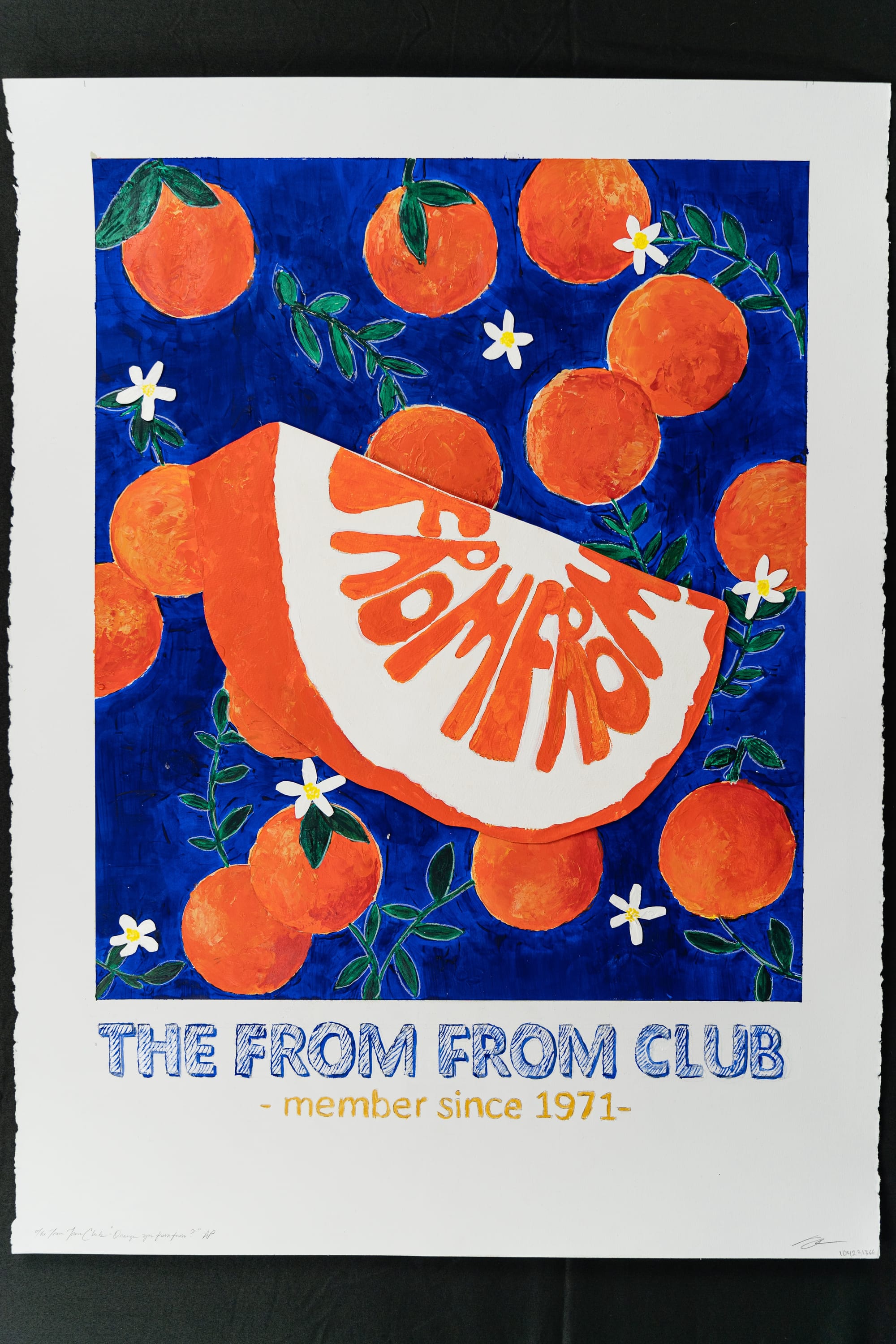

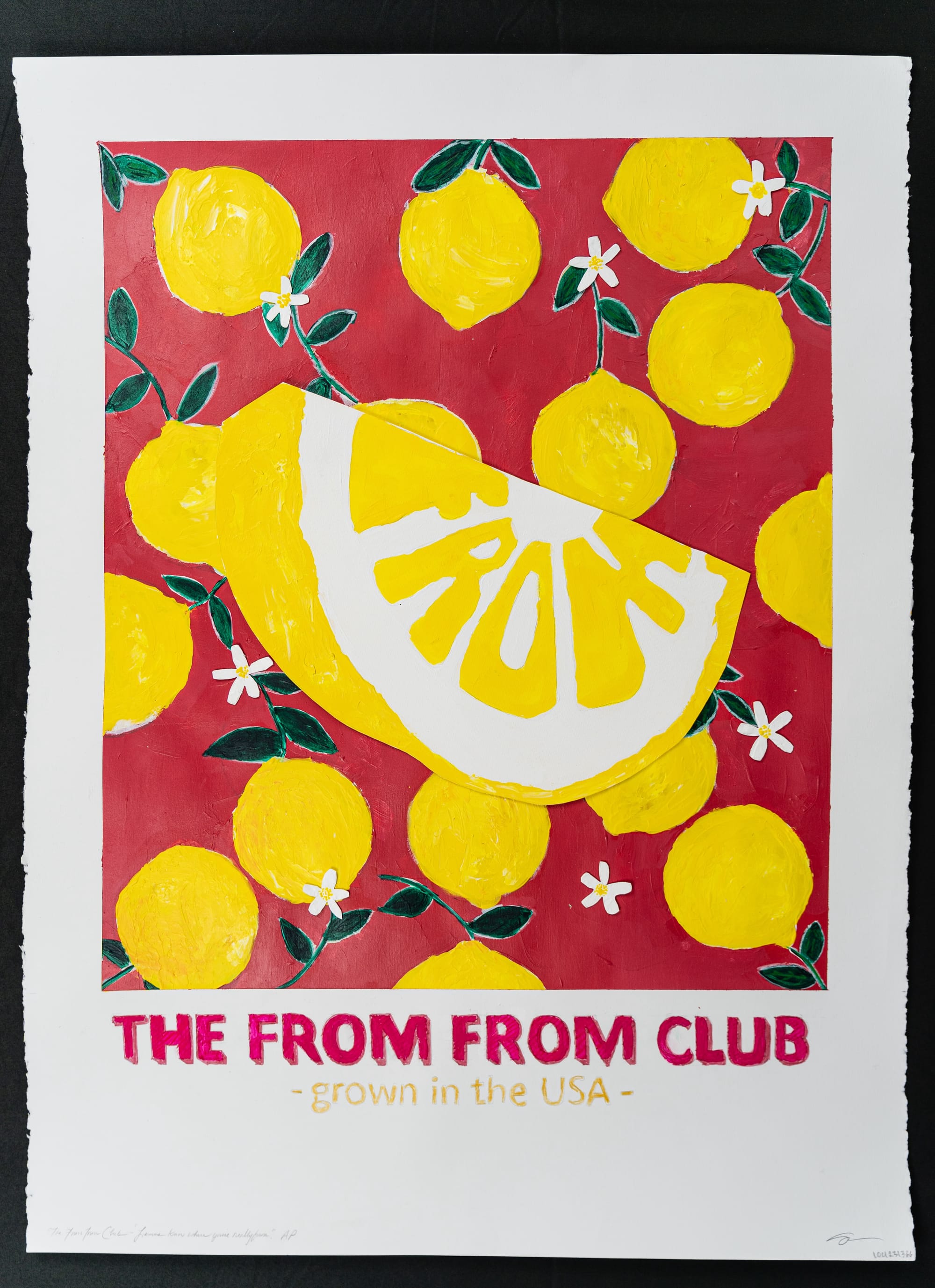

Series like Letters to Invisible People, The From From Club, Ambos, Chaotic Garden, The Mthr Wound, Beauty in the Brokenness, Thick Skin, Los Papis, and Lost in Translation are some of the series born from this time in my life, along with others still waiting to take shape. Each piece holds my truths and my parents’ truths.

I think of my father often — not just the void he left behind, but the incredible gift he gave me, the ability to tell our stories. Through these works, he lives on, no longer invisible.

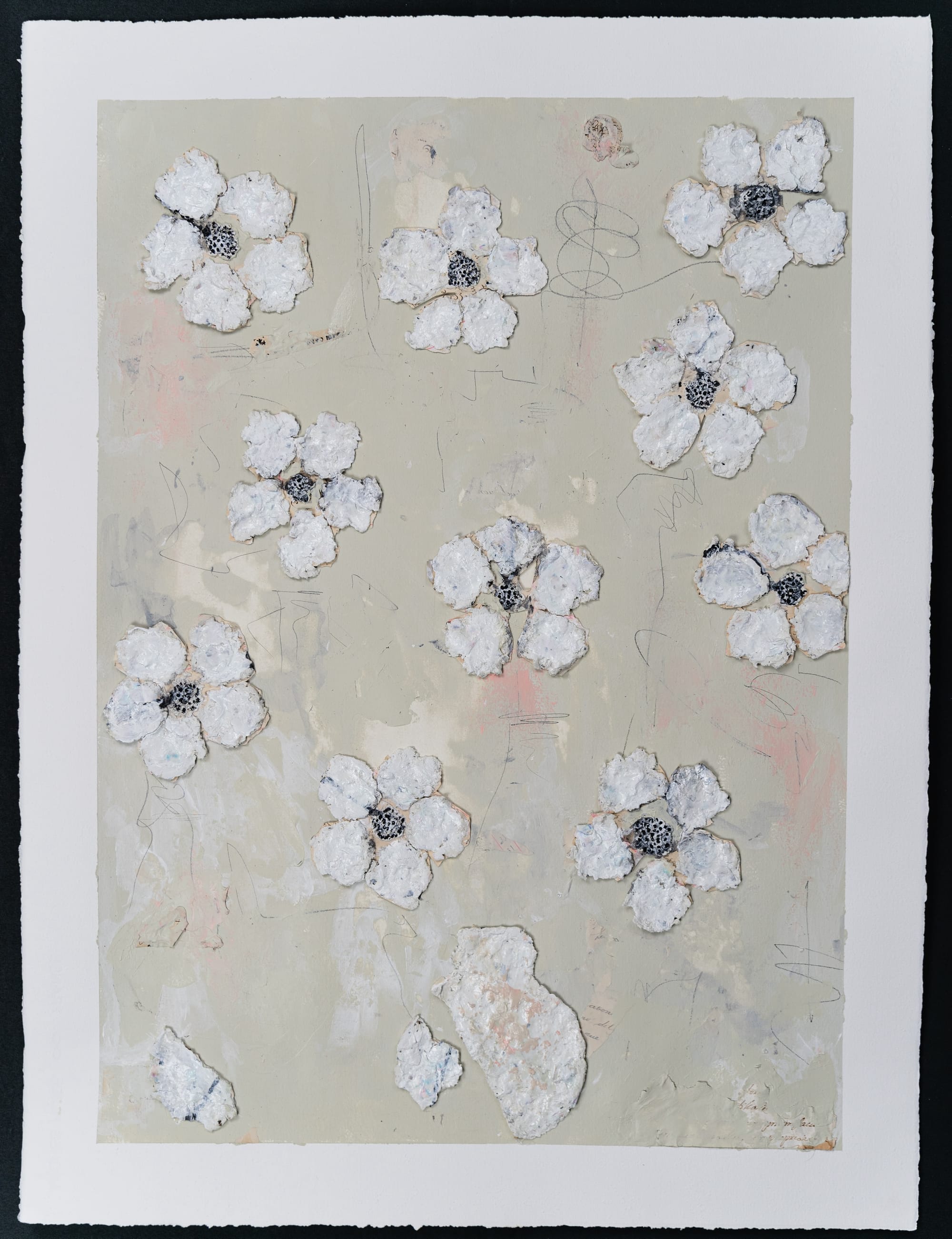

The From From Club / Grace Lieberman

Has art always been an important part of your life?

Yes, creative expression has always been a part of my life. Whether through painting, writing, or collaging, art has always been my way of communicating and making sense of the world.

You described painting for years but taking much longer to identify as an artist. Can you share more about that?

It’s funny how we all start as artists, drawing and creating freely as children. Yet somewhere along the way, many of us stop claiming that identity. Imposter syndrome creeps in, and we convince ourselves that if we don’t pursue art academically, professionally, or achieve a certain level of recognition, we can’t call ourselves artists.

For a long time, I used vague descriptions like “a purveyor of thoughts in my head” or “a creative” instead of simply saying, “I’m an artist.” But over time, I realized that being an artist isn’t about external validation or a job title; it’s about how you see and engage with the world. Thankfully, times are changing, and there are more spaces and opportunities for artists to share their work without needing [to follow] a traditional path.

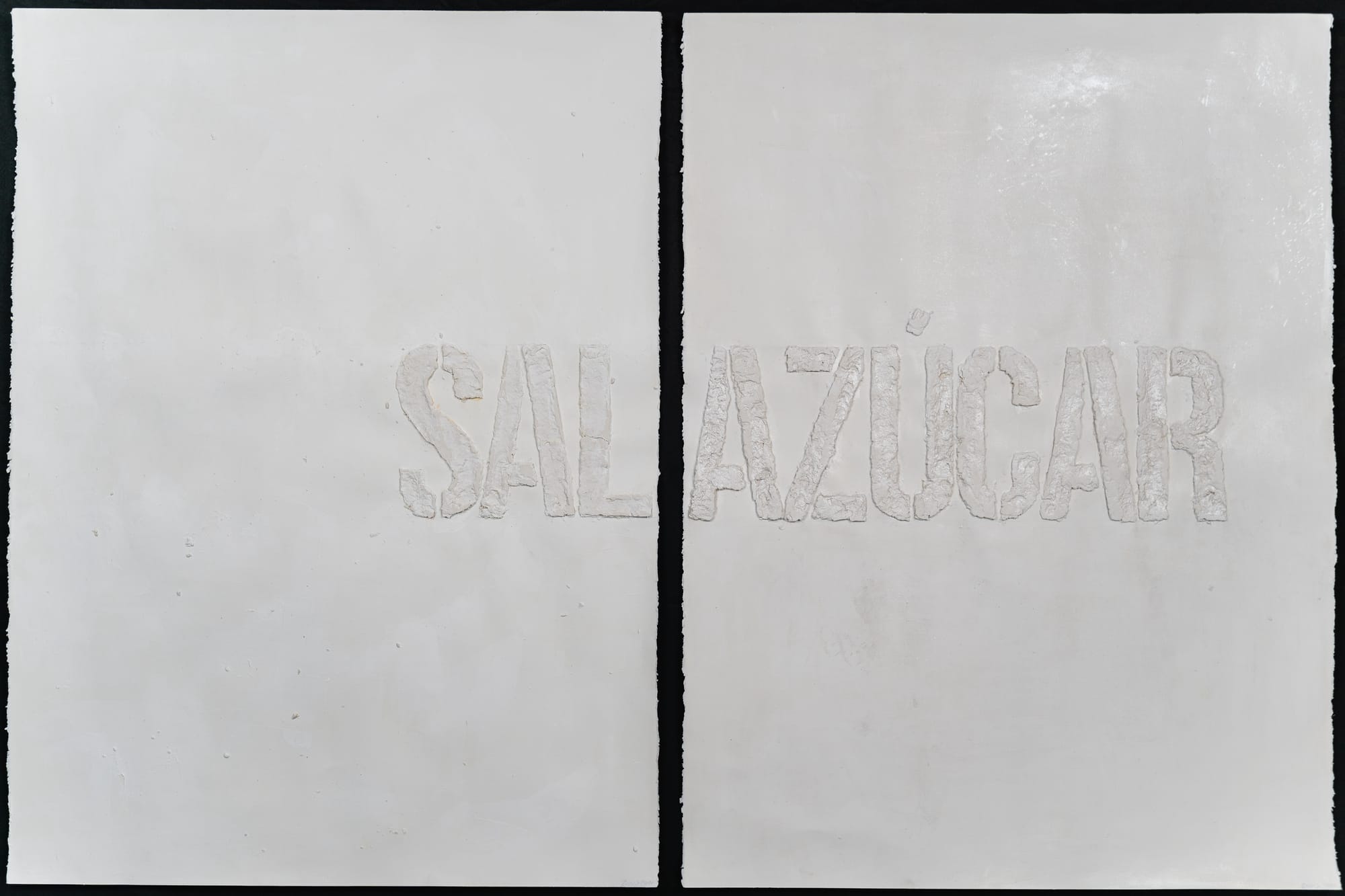

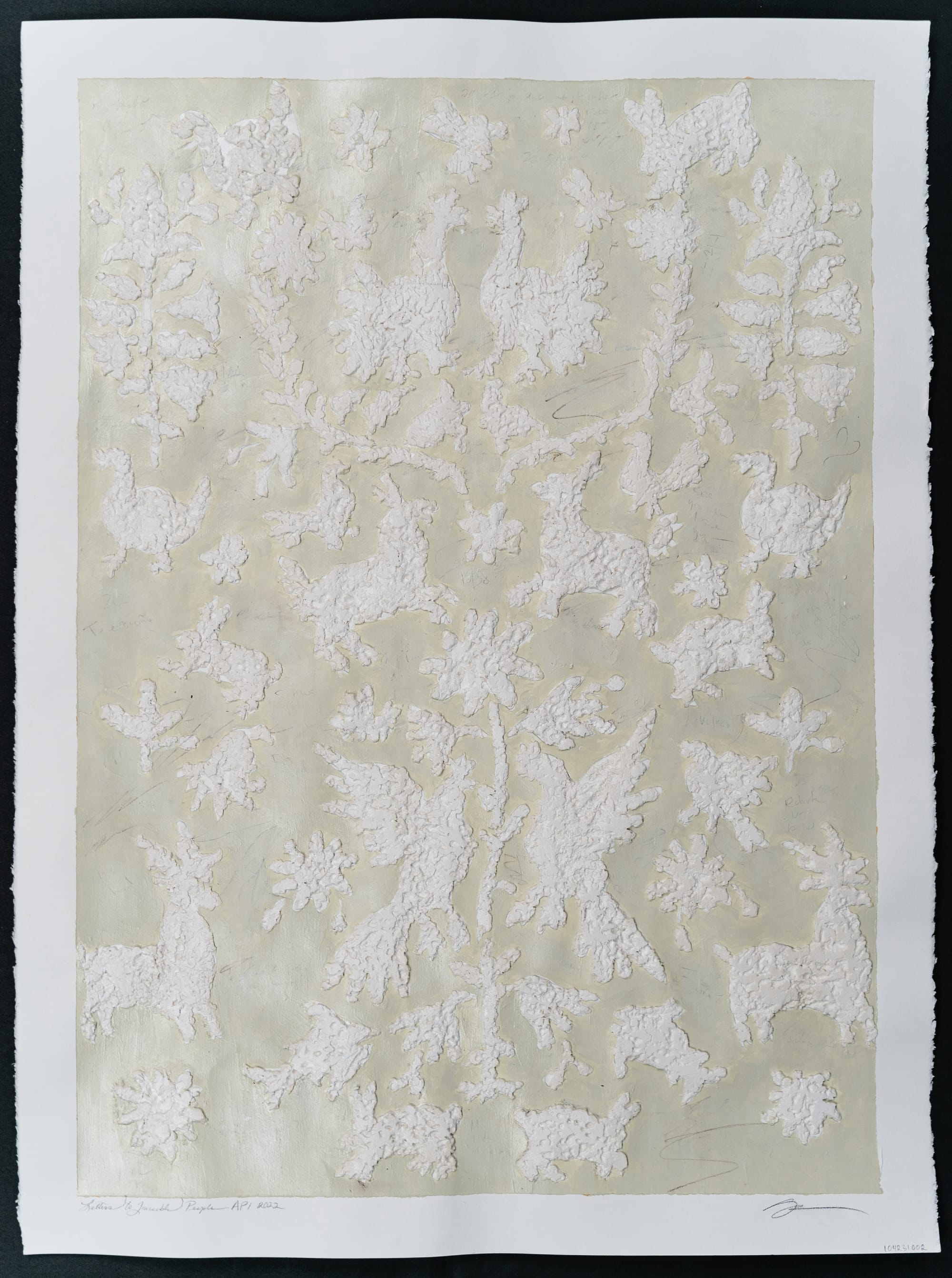

FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: Ambos Salazucar, Letters to Invisible People, Los Papis Bloom / Grace Lieberman

What would you say to other creators, painters, and makers who shy away from the word ‘artist’?

Andy Warhol put it perfectly: “Don’t think about making art, just get it done. Let everyone else decide if it’s good or bad, whether they love it or hate it. While they are deciding, make even more art.”

I spent too much time worrying about whether my art was ‘good enough’ before I would call myself an artist. I was afraid of how others might perceive it — as if their opinions determined my legitimacy. If age has taught me anything, it’s to stop seeking permission and just create. Art exists because we make it, not because someone else approves of it.

You shared how returning home and being open to your parents’ stories was pivotal for you personally and as an artist. How did artmaking play a role in that shift?

For a long time, I felt like I was just painting on the side, creating pieces that were decorative or based on other people’s stories. I worked full time in another profession and then had a family, so I never fully embraced the idea that I was an artist.

When I returned home and was confronted with my father’s mortality, everything shifted. I no longer had a full-time job to distract me; and for the first time, I had the stillness to truly listen, absorb the depth of my parents’ stories, and reflect on my own. That was the moment my work became deeply personal. Instead of just painting, I was documenting, preserving, and honoring history. That’s when I finally accepted and embraced my identity as an artist.

What materials do you usually work with, and how did you discover your preferences?

I primarily work with acrylic, charcoal, and paper-mâché, though I’ve been experimenting more with collage and gouache. I started incorporating paper-mâché while creating Letters to Invisible People and Ambos because I wanted to add texture and embed hidden elements like notes, letters, and personal histories.

Also, the process of working with paper-mâché reminded me of making tortillas, which added another layer of significance to my work. It became more than just a material choice, it became a way to connect to my ancestry, to the hands that came before mine, shaping and layering meaning into each piece.

How do you maintain your practice, and what helps when you don’t feel motivated or inspired to create?

I don’t have a dedicated studio, so my dining room doubles as my workspace. It’s not the most convenient setup — I have to clear and reset my space every time I create — but despite that, I need to make art. When I start feeling restless, frustrated, or out of balance, it’s usually a sign that I’ve gone too long without creating.

If I’m not feeling motivated, I don’t force it. Instead, I engage in other experiences that feed my soul and creativity: exercise, music, travel, or time with family. Inspiration isn’t something you can chase, but I’ve found that when I nurture other parts of my life, creativity usually finds its way back.

Do you have any rituals or routines around your creative practice?

Music and scent play a big role in my process. I create playlists specific to different series, and for commissioned pieces, I sometimes build a custom soundtrack to immerse myself in the mood of the work.

For significant pieces, I light my favorite candle, and sometimes I even mix its wax into the artwork, embedding a small piece of its history into the piece itself. Since many of my works incorporate paper-mâché, my setup often feels like a kitchen: mixing bowls, a tortilla press, even cookie cutters. Lately, I’ve realized I need an apron as I’ve lost too many clothes in the process.

Who are some of your favorite artists?

I have so many favorites, but the top three that immediately come to mind are Cy Twombly, Francine Turk, and Teresita Fernández.

What would you say to community members looking to support local artists and the arts in our area?

Art is deeply personal, but it also transforms spaces in ways nothing else can. I once worked for an artist and quickly realized how original work carries an energy — something that mass-produced pieces simply don’t. I collect original works and limited edition prints myself, and I feel a strong connection to both the pieces and the artists behind them.

If you love art, ‘invest’ in it. Not just financially, but by engaging with and supporting the artists in your community. I put ‘invest’ in quotes because I don’t subscribe to the idea of the ‘starving artist’. Artists deserve to be paid for their work, just like anyone else. When you support their work, you allow them to keep creating, and that’s invaluable.

https://www.artworkarchive.com/rooms/grace-188eccfc-5425-4b51-9209-bfeeb2c245e8/16383f