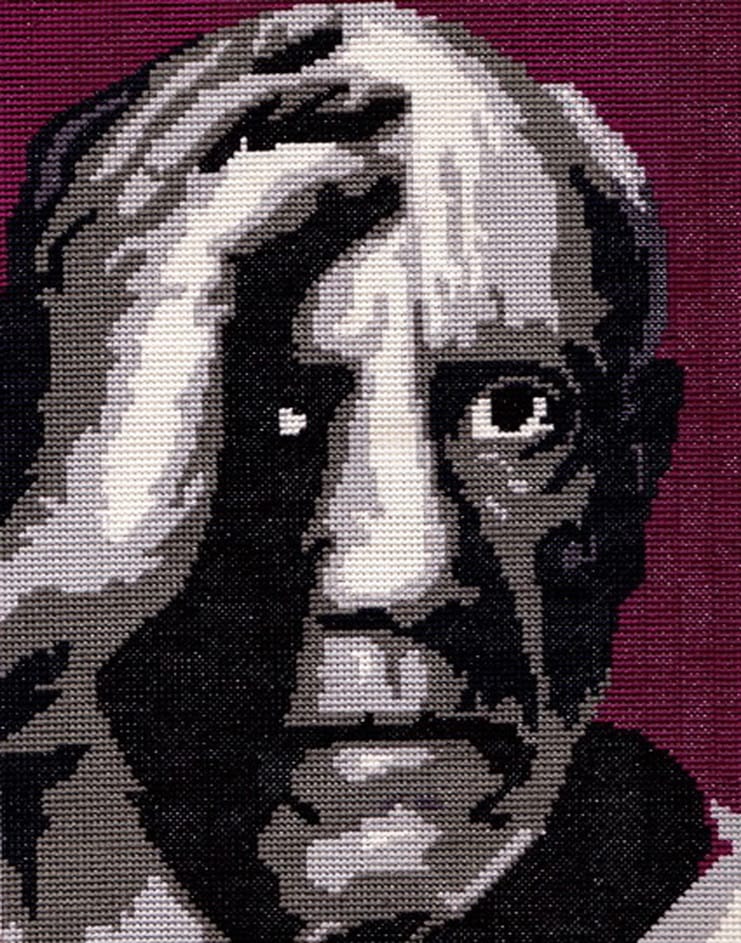

Frank Zappa (2013) / Cross-stitch by Nathan Plung

Let us begin this story in the middle of my life, when I fully embraced my identity as a fiber artist.

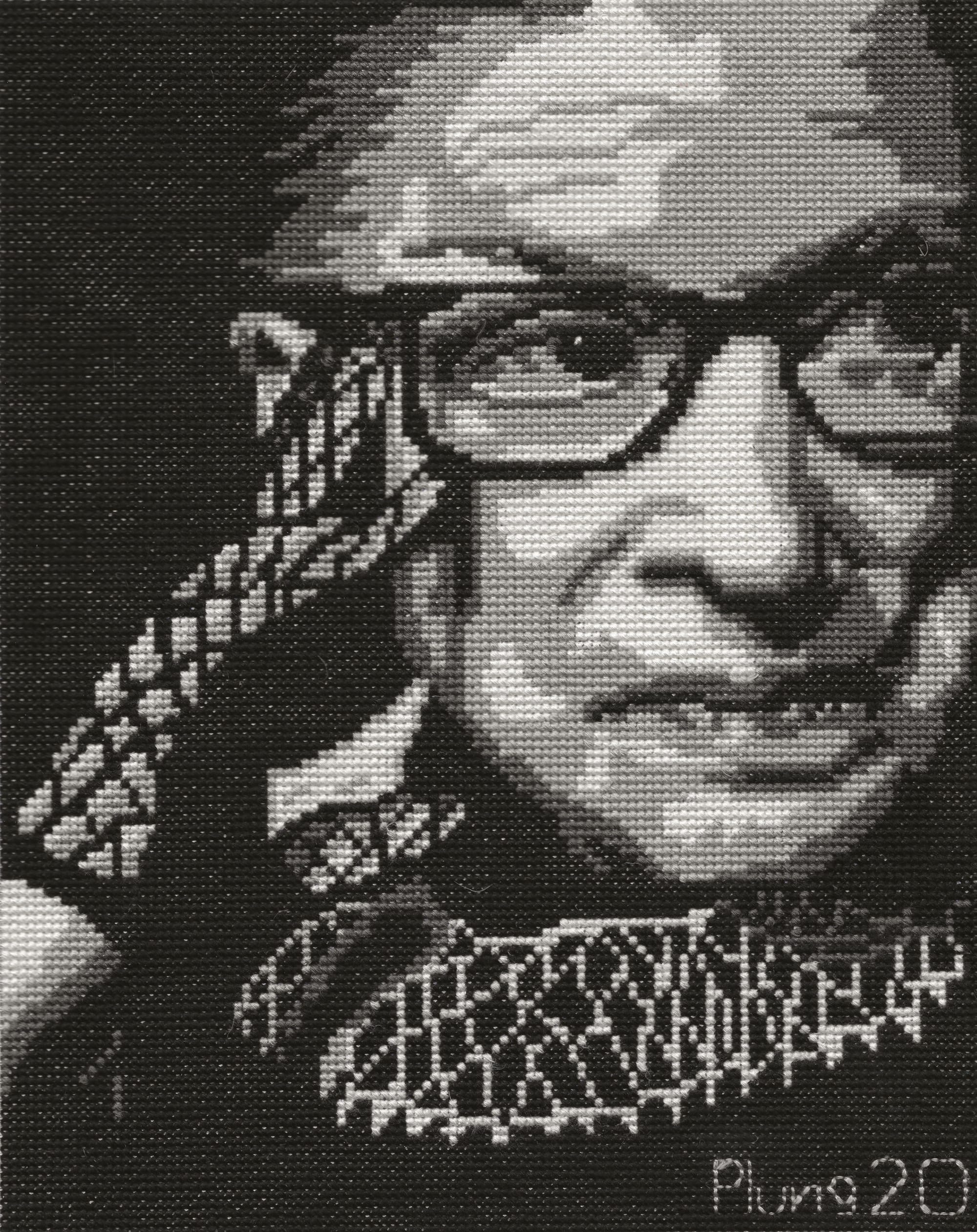

Although I began doing cross-stitch when I was eight years old, I consider the thought of myself as an artist is traced more directly to the two and a half years I lived in England a little over a decade ago. In a country that raises more than 70 breeds of sheep, fiber arts are basically a national pastime, and the quality of the work is outstanding and inspiring. So, when I entered some of my pieces into some local and regional exhibits, I was surprised and gratified by the positive reactions they drew. Creating representations of great masterworks by artists like Picasso and Chagall, as well as creating portraits of writers, artists, and statesmen out of embroidery floss, seemed as foreign to the fiber arts community as my accent and some of my habits.

And, somehow, during that period before leaving England to return to Washington state — I honestly don’t know how it was arranged — I was invited to do an interview with BBC Radio. During that broadcast, the host of the interview asked a curator from one of the area’s art museums what, to me, was a question I had never asked myself: “Is Nathan’s work ‘art’?” The curator unhesitatingly answered, “Yes.” It was an amazing boost to my work (and to my self-esteem).

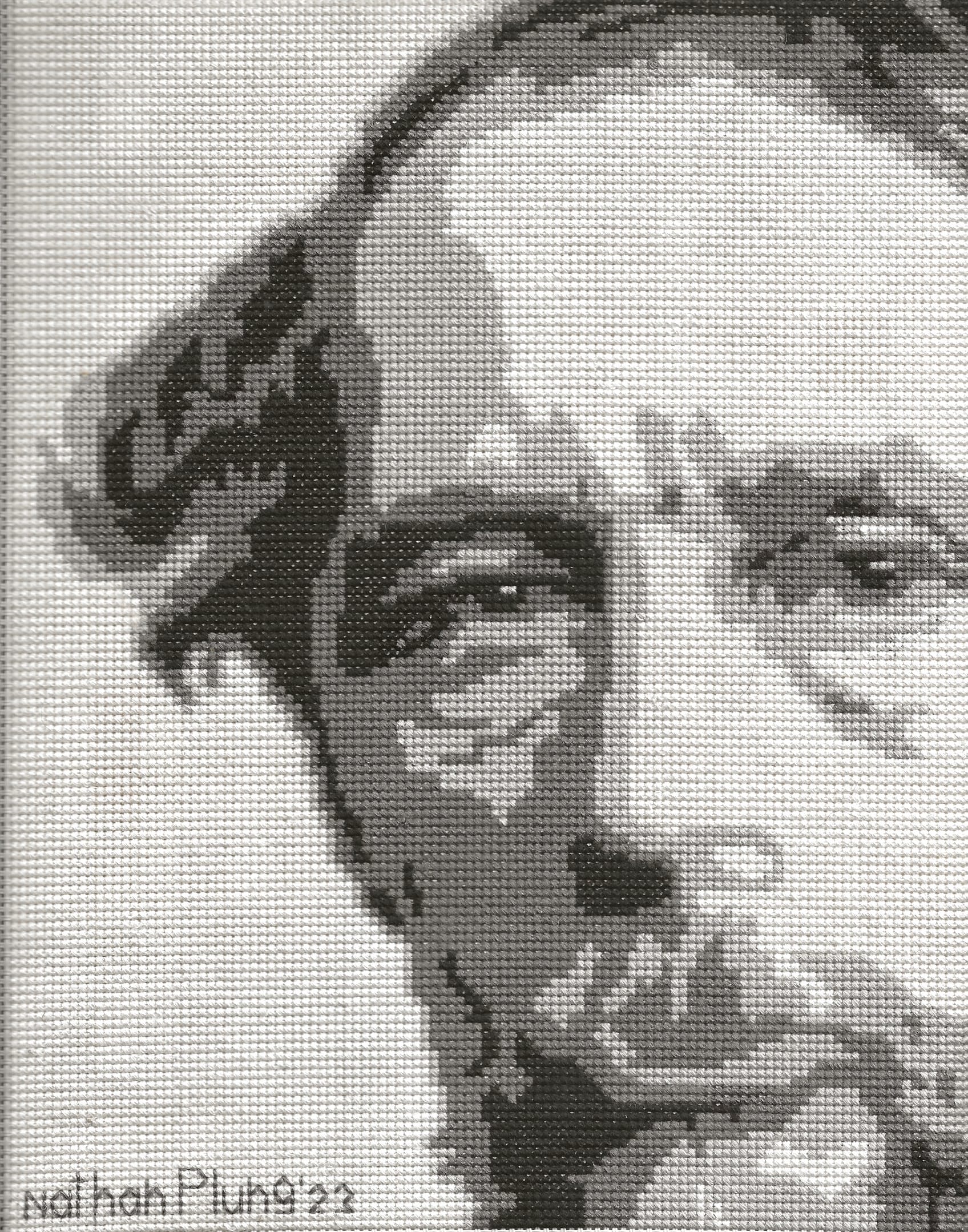

RIGHT TO LEFT: CJ & North (2019), Pablo Picasso (2012) / Cross-stitch by Nathan Plung

So, with that immodest introduction, let us go back in time to where it all started.

I was born with cerebral palsy (CP) and epilepsy — circumstances that entail significant physical and auditory processing challenges. My epileptic seizures have been effectively controlled by medications and a device known as a vagus-nerve stimulator (basically a pacemaker that is threaded from my chest to the vagus nerve in my neck, which leads to my brain). Unfortunately, the weakness in my right side consequent to the CP has demanded years of occupational and physical therapy, complemented by continuing, day-to-day work on my part.

Bolstered by the persistence of my parents and buoyed by a strong sense of self, I successfully put these challenges into a manageable perspective. That said, despite all the support and therapy, what remained the biggest challenge as I reached grade school — the major hurdle that kept me from feeling like I fit in with the other kids — was the weakness and lack of dexterity in my right hand.

I always felt different when I would have to be pulled out of class because of my learning differences to go to my resource class or when I would be taken out for various therapies, PT, OT, and Speech. Other kids did not understand why I was being treated differently. In school, when playing sports in PE (specifically basketball), I always felt others treated me differently by stopping the game so I could make a shot. Although it was their way of being nice, it still felt isolating because I understood why they had that reaction, even at a young age.

Then, I discovered cross-stitch.

The breakthrough came when I was given a cross-stitch kit at 12 years old, for making a baby’s bib. It was a tough physical challenge using my left hand for stitching and my right to hold my cross stitch scroll. Unlike my day-to-day exercises, the bib project gave me a means to gauge progress and a defined, tangible goal; I was creating something tangible.

With the help of my mother, who roughed out pictures on canvas, I moved on to increasingly complex projects, eventually honing in on representations of various artworks, like Chagall’s Green Violinist and Picasso’s Woman With A Book (still my father’s favorite). While I found these works of art to be interesting and colorful challenges, over time, I recognized that what really intrigued me were people.

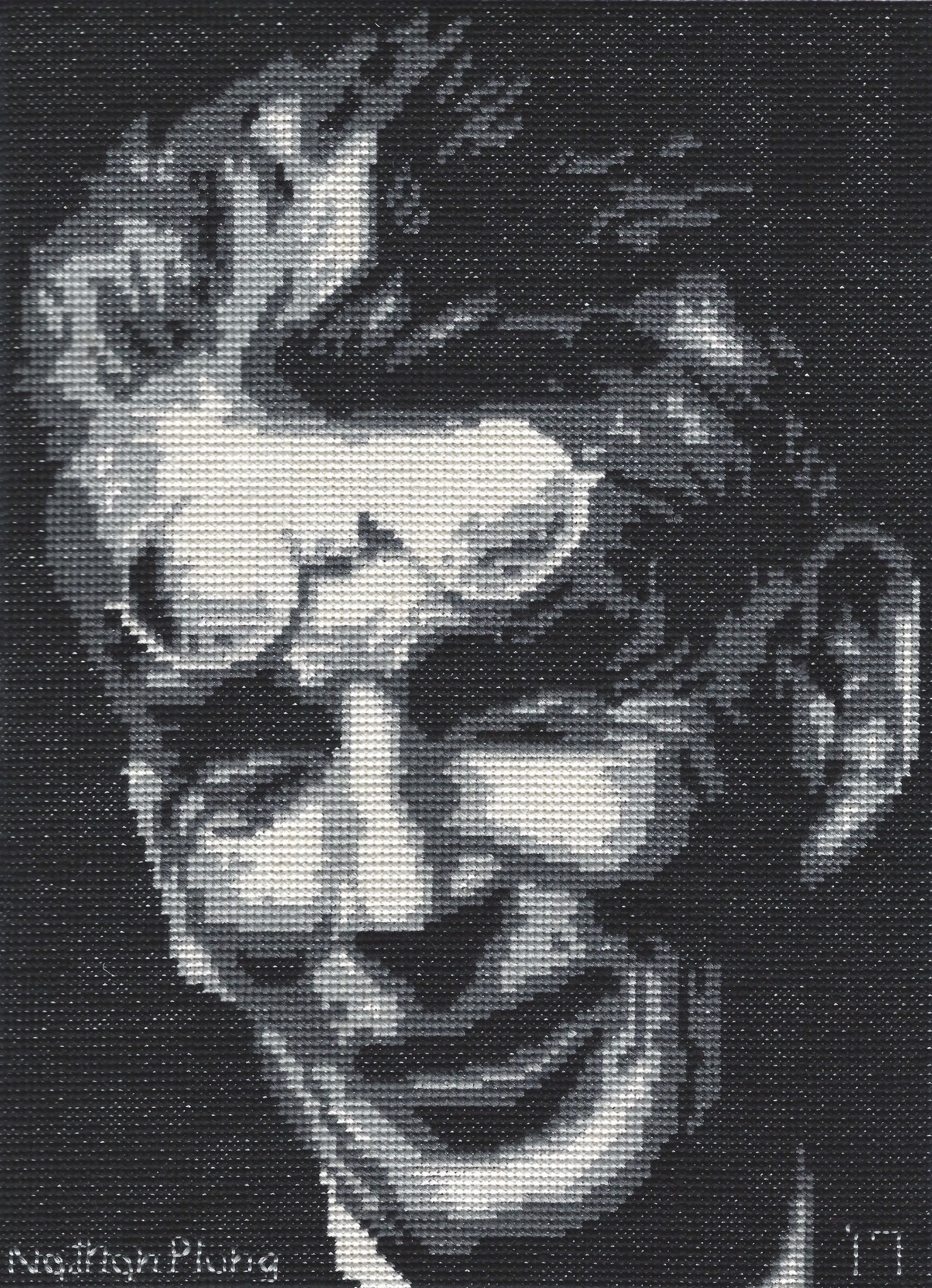

I loved studying the character and temperament in people’s expressive faces, and began recreating them in cross-stitch portraits. I was especially drawn to people whose life works and values resonated with my own.

It was, in a way, my personal means of approaching one of the most profound challenges of life and art: maintaining one’s artistic perspective — a thought captured in a memorable quote from Picasso: “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.”

Portraiture has remained my focus for the last two decades. Perhaps the sole major change in style over the intervening years has been the transition from portraits with color accents to works done almost exclusively with black, white, and grayscale thread. Although working in grayscale is somewhat more difficult to get precisely the effects I am after, the resulting starkness, in my opinion, intensifies each piece’s impact by focusing attention on the subject, and it better reflects my artistic vision.

LEFT TO RIGHT: Charles Dickens (2022), Ruth Bader Ginsburg (2020), Samuel Beckett (2017) / Cross-stitch by Nathan Plung

Which brings us to another important personal value: community.

Upon returning from England in 2012, I began regularly participating in local and regional art fairs. Although not particularly successful in terms of sales, the art fairs had another benefit for me: community building. They gave me cause to interact one-on-one with people, and provided a forum to talk about my art and interests. Often, they also led to engaging discussions about the challenges faced by people with disabilities — discussions that helped me become an active advocate for other people facing physical, developmental, and intellectual challenges.

Today, I enjoy a meaningful and rewarding career working with intellectually disabled adults at Columbia Ability Alliance. I have also been given the opportunity to engage with a community of other artists who have epilepsy. For the past several years, I have been part of an annual art exhibition put on by the Hidden Truths Project, an organization with the mission to raise awareness about the pervasiveness of the hidden disability of epilepsy, and to improve the quality of life and well-being for these individuals, their families, and caregivers.

Hidden Truths Project’s Art of Epilepsy exhibitions take place all across the U.S, and facilitate interactions between hundreds of attendees and a handful of talented artists with epilepsy. Associations from community events like these often spawn other avenues for engagement and advocacy. In my case, I have had work showcased at the National Institute of Health in Washington, DC. My work has also appeared on the cover of an issue of an international medical journal dedicated to the study of epilepsy.

Now, all I have to do is keep moving forward.

Of course it is always gratifying when one of my pieces is shown or sells, but the real, intrinsic value of creating art is what sustains me. In each piece, I try to invoke the echoes of that child I once was — the one who discovered the joy of creating portraits.

At the same time, I feel a sense of modest accomplishment. Martin Luther King, Jr, when speaking about people facing significant, personal challenges, once said: “If you can’t fly, then run; if you can’t run, then walk; if you can’t walk, then crawl. But whatever you do, you have to keep moving forward.”

Art, for me, is the way I keep moving forward.

Nathan Plung is a fiber artist with cerebral palsy and epilepsy who lives and works in Tri-Cities, Washington. He finds joy in creating one-of-a-kind portraits, and in spending time in nature swimming, kayaking, and hiking. Nathan holds a Bachelor's degree in Human Services from Beacon College and a Master of Arts in Disability Studies from the City University of New York.

Website: www.nathanplung.com

Instagram: @nathanplung