Chuck Eaton completed his doctoral studies at Columbia University in Behavioral Science. He worked at the New York City Department of Health for a decade, in the middle of the HIV epidemic, after a career in drug use prevention and treatment. While there, he was trained in Epidemiology under supervision of the CDC.

I hear with interest that the Benton-Franklin Health District is asking for volunteers to become contact tracers in the midst of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ten years ago, I would have been the first one in line, with my hand waving, “Pick me! Pick me!”

Alas, at 82, with COPD, not walking too well, I have to stay at home, keep my social distance, wear a mask and wait. So I have plenty of time to observe what we are doing and anticipate the results.

The picture is not good.

What I see is well-informed attempts to establish the right policies to curtail the spread of the virus and ill-informed attempts to disrupt those policies, with endless discussion on both sides, quoting numbers that have no relation to good policy making.

I especially see little understanding of public health, which allows us to do the right thing even when we don’t have enough tests, a vaccine, or a cure.

The most important information can be explained in a non-technical way, but it is a bit complicated, takes some time to think through, and won’t fit in a meme or tweet. So here is my attempt to explain it, based on my scientific training and practical experience observing how public health works. I will also have some suggestions to overcome lack of resources and keep us healthy.

Until we have available and accurate testing used to support a strategic plan of public health measures, we only have the policy of “stay home, stay safe, no groups” to flatten the curve. In the Tri-Cities, I fear we are not doing that well enough. Fourteen days of a flattened curve with public health measures in place is a good criterion before we ease restrictions; we are not there yet.

We are not using the limited available testing in a way which supports the public health strategy. The strategy for using available testing would be:

- Systematically test a population we suspect or know is at high risk of being infected, like the meat packing plants, health workers, etc.

- Use BFHD contact tracers to interview those who test positive to identify those with whom they have been in recent contact, and interview and test the contacts.

- All positive-testing people would be quarantined.

- Then keep repeating until we can’t find any more.

This would give us increasingly complete answers to who, what, when, and where the virus is hitting us. When treatment—and eventually a vaccine—are available, we would know how and where to use them.

After talking with the BFHD, this is what I understand.

A reasonable estimate of trained contact tracers needed is about 30 per 100,000 people. Washington State currently has 628 for 7.615 million people, or about 8.25/100,000. Washington State plans to hire more contact tracers, bring us to 750, and then double that number by adding 750 from the National Guard. This would be close to 20/100,000. How many of these contact tracers would be assigned to the Tri-Cities is unclear.

BFHD originally had about six staff members who could do contact tracing and has increased that number to eighteen through hiring and recruiting volunteers. The number fluctuates depending on assignments and volunteer availability. Ideally, BFHD would have 90 contact tracers. The only way they will be able to have more is if they can get volunteers. BFHD is able to do contact tracing at the current volume of COVID-19 cases, but will become overwhelmed if the number of cases significantly increases.

Contact tracing is a difficult job. It is traditionally done in person because the health worker needs to get the trust of the individual thought to be infected, in order to obtain the sometimes personal information necessary to reach contacts. It will be difficult to establish the necessary trust between the patient and the contact tracer over the phone (which seems to be the current plan for contact tracing). How that will work I don’t know. I’m afraid I wouldn’t be responsive to calls from unknown numbers.

People don’t seem to understand that until we have available testing, effective treatment, and a vaccine, the only methods that flatten the curve are public health measures.

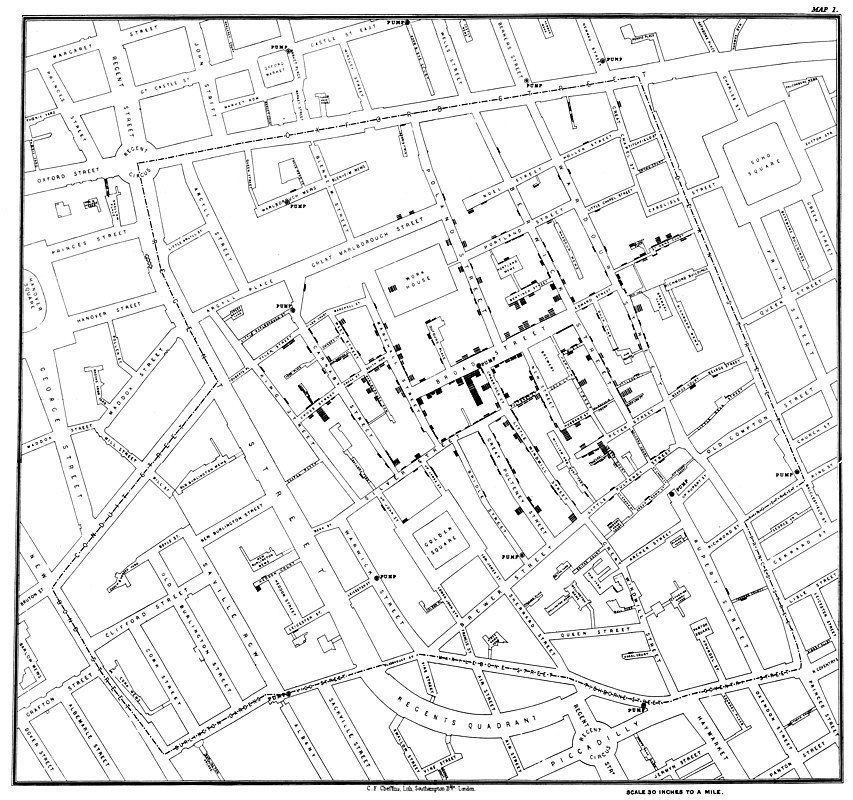

I wish every student learned in middle school the remarkable story of John Snow and how he stopped a cholera outbreak in London before anyone knew what caused cholera. (You’ll see his map at the top of this article.) This story is not only the beginning of epidemiology but is also the story of adapting the already existing technology of mapmaking to graphically communicate dissimilar data simultaneously. Talk about laying a foundation for Information Technology!

We do not have the testing we need—for epidemiology, contact tracing, or research. We are not using the testing we have to generate data we need. It is not that the data on the number of tests which give positive results and the number of deaths are wrong; it is that those chosen for testing don’t tell us who and where the pandemic is in a way that allows us to do anything about it.

Drive through testing makes matters worse. The number of tests gives us the number of people worried enough to say they have symptoms and wait for hours in line. The number of positives tells us the number of those drivers who have COVID-19 and can transmit it to others or who don’t but tested positive (false positives).

False positive rates for available tests differ but are assumed to be small. The number of negatives tells us only that the test is negative; the person tested may not have COVID-19, they may have had it and no longer shed the virus, or they may be a false negative. False negative rates have been estimated to be as high as 40% for some tests.

A great opportunity has been missed as the administration just fired 7,300 Peace Corps Volunteers, some of whom have public health experience. An undetermined number of National Service Corps Volunteers have also been fired. If these young people were at risk in their positions, they could have been quickly retrained as contact tracers and made available where most needed, as determined by focused testing. They could have been a positive start to a national employment program to restore public health.

We now have a cohort of college seniors, many of them science majors, who are now uncertain about their employment possibilities or graduate school. We also have a cohort of graduating high school students who planned to major in health sciences but who are now uncertain about college being open in the fall, or how they and their families will pay for college. They could follow the Peace and National Service Corps, be trained and supervised by them as a National Public Health Corps, and do the contact tracing necessary to prevent the second wave of COVID-19. Bi-partisan plans to introduce bills to do exactly this are pending in both the House and the Senate. Johns Hopkins has just announced an introductory, free, online, 5-hour course on COVID-19 contact tracing.

Alternatively, the County Commissioners who jointly serve on the Board of Health could fund the BFHD to the level where they could hire, train, supervise and support 90 contract tracers with the levels of testing, access to primary care, and other services needed. Unfortunately, that scenario is not very likely.

The curve is flattening in Washington State. I hope we take the steps necessary to keep the COVID-19 pandemic under control, but I fear we will not.

If we do not engage in a strategic public health response that includes testing and contact tracing, we will have learned nothing from 100 years of experience and science since the Great Flu Epidemic in 1919. We will have a devastating second wave like they did, and some of us who could have otherwise survived will not.