For a man born to a long lineage of Washington state lumberjacks, I am quite a British stereotype. When people hear my accent, I get questions like, “What’s your soccer team?” (Crystal Palace), “Have you met the Queen?” (Yes, and I embarrassed myself), and “Did you go to boarding school like Harry Potter?” (Why yes, yes I did). It’s a slightly uncomfortable conversation for me, as it’s very much something rich kids normally experience, and I was not a rich kid. I always start trying to explain in great depth how I got there, which makes people very bored very quickly. So right now, while we are all attempting to go back to school in some way, I thought it would be a good time to describe boarding school life.

I grew up in South London from the ages of 4–28. My mother remarried when I was five, and her husband David Russell adopted me at that time (they split up after a couple of years). I went to Rosendale Primary School in London, a regular day school with a great mix of middle-class kids from surrounding neighborhoods and kids from the council projects across the road. I was in the middle; not affluent, but not living in the projects.

When fifth grade came along and we started looking at secondary schools, most of my friends got admitted to Alleyns or Dulwich College—very nice private schools. I failed to get into either, so I was headed to Kingsdale, or the ‘Car Theft and Arson State Academy’ in my mother’s eyes. My stepdad had sent his older son to Reed’s, a private boarding school just outside of London. Reed’s was a former orphanage that was now an all-boys school that awarded scholarships to some kids from single parent families, so they decided to get me a tutor to pass the entrance exam. After my dad died on Christmas 1989, one of the consequences of his passing was that the amount that Reed’s would charge us in fees dropped drastically. It was decided; the London boy was headed to the countryside.

I remember the Sunday evening when Mum first drove me down there. As we toured the boarding house, I suddenly realized with terror that Mum would be leaving at some point, and I would be staying. The next morning at the daily chapel service, there were a number of us newbies sobbing silently into our navy- and royal blue-striped ties and tweed blazers.

The school was in the middle of a shift from traditional teacher roles to more personable ones, although some of the teachers would still wander the halls and teach in their university gowns, impressing no one but themselves. Most of our teachers lived on the school campus and had responsibilities that made crosswalk duty seem frivolous.

We would be woken at 7 a.m. by a teacher ringing a handbell in our dorms. Breakfast was at 7:30 a.m. and mostly consisted of toast, cereal, enormous plastic sacks of milk in refrigerated dispensers, and bacon with bones in it. Chapel was at 8:30 a.m., then lessons would take place all day. We even had a few lessons on Saturday morning for a couple of years before sense prevailed in my fourth year. Saturday afternoons were for sports: field hockey, rugby, or cricket. And in the evening after dinner we would watch whatever WWF bouts or Baywatch episodes someone’s mother had recorded and sent in.

We had wooden tuck box chests that were put in a rodent-infested annex, padlocked closed (your padlock was a sign of your wealth and the quality of your stash) in which we stored our candy. There was a main Chapel service on Sunday mornings (which later became Saturdays), normally with a visiting preacher, after which we were allowed to visit home until Sunday evening, if our parents would have us.

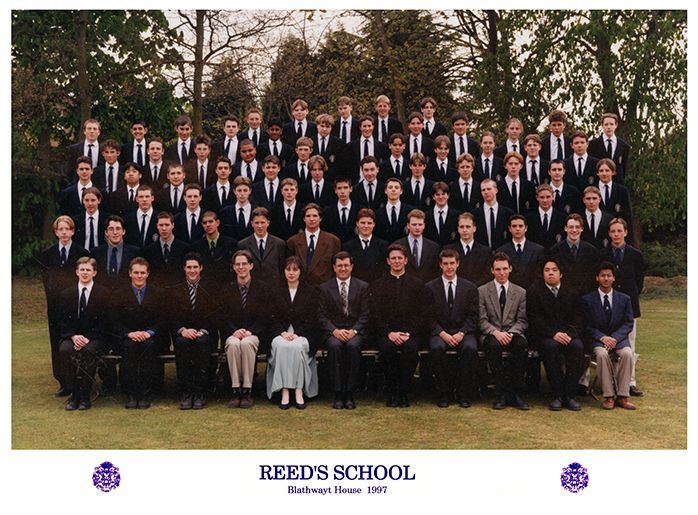

The school had a house system, much like Hogwarts, or my current school, Westgate. We didn’t have a magical sorting hat or sweet spinning wheel, though—we were assigned houses based on family history and pure luck. My step-brother was in Blathwayt, and therefore, so was I. From the third year onward, we lived in our boarding houses, entered sports and arts competitions, wore the house color ties, and maybe one day became prefects.

If we got sick or injured, we had to visit Sick Wing, which was as horrifying as it sounds. Sister Keeney would either admit us to a hospital bed with some very old National Geographic magazines for company, or put a giant band-aid on whatever hurt and sent us on our way. It was so old school that we were given the BCG vaccine against tuberculosis (TB); this proved a problem when I worked for King County Jail Health Services and I gave a false positive for TB. When I explained why I didn’t need a chest X-ray, the technician looked at me like I was Oliver Twist.

My experience at boarding school can be divided into before and after one morning in Sick Wing early in my fourth year. I had a headache and skipped chapel to see Sister Keeney. When she asked what was wrong, I broke down in floods of tears. Mum had just had my youngest brother, and I missed my family like crazy. As I walked out with my giant band-aid, I felt different. I was no longer sent away to school; I was living with my friends. As I got older and discovered Paul’s Boutique, Vodka, and skipping gym class, I became more confident and self-assured.

By the time our senior year came around, we were already a notorious cohort of 33 hard-drinking savages. My 18th birthday in September involved a pub crawl, followed by some weed-laced curry, and ended with me asleep on a picnic table outside a pub before last orders. When I arrived at the school assembly the next morning, I got a round of applause from the back rows, much to the bemusement of the teachers. That wasn’t even the best 18th birthday party. On Paddy's birthday, we broke into the school assembly hall on a holiday weekend and hosted a rather old stripper for a crowd of about 50.

A week later, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, patron of the school amongst other titles, popped by for a visit. The preparations were all-consuming; the school was cleaned like never before and kids were on best behavior warnings. I had many roles to fill during this visit. I started in the welcoming crowd at the front entrance, then snuck around the back into the chapel where I sang in the choir, then around the back again to the gym, where, as deputy head boy, I was going to introduce Her Royal Highness to the other school prefects (at least the few who hadn’t been caught drinking/smoking and thus been demoted). ‘Brenda’ was introduced to pretty much every adult within a 12-mile radius by the time she got to me.

Fully knowing that I couldn’t instigate any conversations or handshakes, I waited for her to greet me, and introduced Peter Otley, Blathwayt House Captain. That was followed by about ten seconds of silence. In hindsight, after having met a couple hundred other fawning servants, it was understandable that it took her a bit of time to think of something to say. I did not have that sort of patience at the time, though. I waited maybe three seconds, then proceeded to introduce her to the next person in line, whereupon she finally decided to ask Pete something banal. I see, she needs some time to think of something to say, is a thought that probably should have gone through my head. However, I decided that Britain’s longest-serving monarch may not have that much time (this was in 1997; she had plenty of time) and made the same mistake all the way down the line. By the time we got to where she was meant to ask me something inconsequential, she gave me a look and wandered off elsewhere. All that was left for me to do was to nip around the back again and reappear at the front entrance to see her off, and pull my friend Alex back from touching the rear fender of her car.

I still consider myself a lower-middle class London lad, and I’m still uncomfortable owning up to being a private school boy. There were maybe three teachers there that I would have considered to be better than any of the teachers at my current school. I had to teach myself how to speak to girls, and the two Bs and a D in my A-Level results were hardly outstanding. Still, coming from such a small grade level cohort, and having lost two of us within a few years of leaving school, I do have a solid, close group of friends located all over the world that I consider to be brothers to me. I may not have learned how to jimmy the lock on a 1987 Fiat Panda, but I did learn how to make very good friends.

Mark Russell is Technology Teacher at Westgate Elementary, and is more proud of being in Verdad house than Blathwayt.

Image courtesy of Mark Russell.